doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.147.87-108

RESEARCH

EXPERIENCES OF COOPERATIVE WORK IN HIGHER EDUCATION. PERCEPTIONS ABOUT ITS CONTRIBUTION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOCIAL COMPETENCE

EXPERIENCIAS DE TRABAJO COOPERATIVO EN LA EDUCACIÓN SUPERIOR. PERCEPCIONES SOBRE SU CONTRIBUCIÓN AL DESARROLLO DE LA COMPETENCIA SOCIAL

EXPERIÊNCIAS DE TRABALHO COOPERATIVO NA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR. PERCEPÇÕES SOBRE SUA CONTRIBUIÇÃO AO DESENVOLVIMENTO DA ATRIBUIÇÃO SOCIAL

Francisco-José Sánchez-Marín1

María-Concepción Parra-Meroño1 Doctora en Administración y Dirección de empresas: Marketing y Organización. Es profesora en el Grado en ADE y en el Master en Marketing y Comunicación y en el Master MBA de la UCAM

Beatriz Peña-Acuña1

1San Antonio Catholic University of Murcia. Spain.

ABSTRACT

The European Higher Education Area (EHEA) requires the development of key competences to respond to the demands of society and the labor market. Social Competence includes fundamental skills for quality social relationships in the personal and professional sphere. Cooperative Learning is identified as an appropriate method to achieve this goal.

This article presents the experience of qualitative research during the 2009-2015 courses in which participatory action research is structured as an appropriate technique, since it researches the sample, a teaching methodology is designed based on the shortcomings and the effectiveness of learning due to the methodology is researched again. We present a case in which participatory action research has been applied to the field of university education in which adaptation to diversity is more precisely assured by the adequacy that it gives to the class under research.

Besides, we present the results of the analysis of this piece of research and innovation, specifically, the perception expressed by the students about the degree to which cooperative teamwork contributes to the development of their Social Competence after participating in a Cooperative Learning experience. A type of applied research is designed, from a qualitative, non-experimental perspective, in the field of evaluation of results for decision making. 126 First and Fourth Grade students participate. Through a Likert-type questionnaire, their perception of emerging competences is gathered in the performance of Social Competence: Empathy, Consensus or Democratic Participation and Assertiveness. This study provides novelty in that it explores a sample of students with diverse profiles, taking as a starting point, in an integrated way, various variables and on the perception that the students themselves express explicitly. It is confirmed that the students perceive that, through Cooperative Learning, their Social Competence is developed. The best valued skills are those related to the cognitive field and others of an emotional, axiological and paradigmatic nature are relegated to a second level.

KEY WORDS: social competence, action research, educational cooperation, emotional intelligence, professional competence, interpersonal communication

RESUMEN

El Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior (EEES) exige el desarrollo de competencias clave para dar respuesta a las demandas de la sociedad y del mercado de trabajo. La Competencia Social incluye destrezas fundamentales para las relaciones sociales de calidad en el ámbito personal y profesional. Se identifica el Aprendizaje Cooperativo como método apropiado para lograr tal fin.

En este artículo se presenta la experiencia de una investigación cualitativa durante los cursos 2009-2015 en la que se vertebra la investigación acción participativa como una técnica adecuada, puesto que investiga a la muestra, se diseña una metodología docente en base a las carencias y se vuelve a investigar la eficacia del aprendizaje debido a la metodología. Exponemos un caso en el que la investigación acción participativa ha sido aplicada al campo de la Educación universitaria en la que se asegura más la adecuación a la diversidad precisamente por la adecuación que otorga al aula investigada.

Además, se exponen los resultados del análisis de esta investigación e innovación, en concreto, la percepción expresada por los alumnos acerca del grado en que el trabajo en equipo cooperativo contribuye al desarrollo de su Competencia Social tras participar en una experiencia de Aprendizaje Cooperativo. Se diseña un tipo de investigación aplicada, desde una perspectiva cualitativa, no experimental, en el ámbito de la evaluación de resultados para la toma de decisiones. Participan 126 estudiantes de Grado de primer y cuarto curso. A través de un cuestionario tipo Likert, se recoge su percepción sobre competencias emergentes al desempeño de la Competencia Social: Empatía, Consenso o Participación Democrática y Asertividad. Este estudio aporta novedad en tanto que explora sobre una muestra de estudiantes con perfiles diversos, tomando como punto de partida de manera integrada diversas variables y sobre la percepción que los propios estudiantes expresan de manera explícita. Se confirma que los estudiantes perciben que, a través del Aprendizaje Cooperativo, se desarrolla su Competencia Social. Las habilidades mejor valoradas son las que se relacionan con el ámbito cognitivo y se relega a un segundo plano otras de carácter emocional, axiológico y paradigmático.

PALABRAS CLAVE: competencia social, investigación acción, cooperación educativa, inteligencia emocional, competencia profesional, comunicación interpersonal

RESUME

O espaço europeu de Educação Superior (EEES) exige o desenvolvimento de atribuições chave para dar respostas as demandas da sociedade e do mercado de trabalho. A Atribuição Social inclui destrezas fundamentais para as relações sociais de qualidade no âmbito pessoal e profissional. Identifica-se o Aprendizagem Cooperativo como método apropriado para lograr essa finalidade. Neste artigo apresenta-se a experiência de uma investigação qualitativa durante os cursos dos anos 2009-2015 na qual estrutura a investigação ação participativa como técnica adequada, investigando a amostra e desenhando uma metodologia docente com base as carências e eficácia da aprendizagem devido a essa metodologia.

Expomos um caso no qual a investigação ação participativa foi aplicada ao campo da Educação universitária na qual se assegura mais a adequação do que a diversidade precisamente pela adequação que outorga a aula investigada.

Ademais, expõe-se os resultados da analises desta investigação e inovação, em concreto, a percepção expressada pelos alunos aproxima. Do grau no qual o trabalho em equipe cooperativo contribui ao desenvolvimento de sua atribuição Social depois de participar em uma experiência de Aprendizagem Cooperativa.

Se planeja um tipo de investigação aplicada, desde uma perspectiva qualitativa, não experimentada, no âmbito da valoração de resultados para a toma de decisões.

Participam 126 estudantes do primeiro e quarto ano do curso universitário. Através de um questionário tipo Likert, são coletadas suas percepções sobre atribuições emergentes ao desempenho da Atribuição Social: Empatia, consenso ou participação Democrática e Assertividade. Este estudo aporta novidades já que explora sobre uma amostra de estudantes com diversos perfis, tomando como ponto de partida de maneira integrada diversas variáveis e sobre a percepção que os próprios estudantes expressam de maneira explicita. Confirmando que os estudantes notam que, através da Aprendizagem Cooperativa, desenvolvem sua Atribuição Social. As habilidades mais valorizadas são as que se relacionam com o âmbito cognitivo e se relega a um segundo plano outras de caráter emocional, axiológico paradigmático.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: atribuição social, investigação ação, cooperação educativa, inteligência emocional, atribuição profissional, interpessoal

Correspondence: Francisco José Sánchez Marín. San Antonio Catholic University of Murcia. Spain.

fjsanchez235@ucam.edu

María Concepción Parra-Meroño. Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia. España.

mcparra@ucam.edu

Beatriz Peña-Acuña. San Antonio Catholic University of Murcia. Spain.

bpena@ucam.edu

Received: 25/04/2018

Accepted: 04/04/2019

Published: 15/06/2019

How to cite the article: Sánchez-Marín, F. J., Parra-Meroño, M. C., and Peña-Acuña, B. (2019). Experiences of cooperative work in higher education. Perceptions about its contribution to the development of social competence. [Experiencias de trabajo cooperativo en la educación superior. Percepciones sobre su contribución al desarrollo de la competencia social]. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 147, 87-108.

http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.147.87-108. Recovered from http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1123

1. INTRODUCTION

This dissertation presents the application of participatory action research with a beneficial character for educational innovation, specifically, in university education. During the 2009-2012 courses, lack of teamwork skills on the part of the students was detected by the professors. In addition, this issue was seen as an urgent need for vocational training in line with the Bologna framework. This reality was observed and commented every year in the three course meetings by the professors.

In the following course (2013-2014), several professors who were also observing it in a participative way decided to carry out a pilot project through participatory action research to a group of 50 students who were taking the subject of “Social Skills” in the degree of Teaching. Following Peña (2014), the following tools are deployed. First, he carries out a previous questionnaire to the students in which open questions are asked about teamwork skills in a general way. Second, he taught two classes with basic notions of teamwork skills. Third, he followed up the work of the teams, held discussion groups on their development, interviewed some students and conducted a survey at the end of the course to see what improvements students perceived on their teamwork skills and what skills they highlighted as most necessary. From this study, three variables and certain manifestations about them stood out: the attitude of consensus, assertiveness and empathy.

Afterwards and thanks to this participatory action research, a multidisciplinary group of 13 professors and researchers applies a Cooperative Teaching Innovation Project in order to encourage students to develop their Social Competence, through training in communication skills, using strategies of Cooperative learning. The project was financed with a duration of 12 months (PMFI PID 14-14) during the 2014-2015 academic year. Since the beginning, it is projected that first it is the professors who must learn to work as a team. This is done by creating a shared materials folder in Google Drive. In addition, work teams are formed to create the texts and protocols of action of the teaching staff participating in the project. This way, professors carry out research on these project concepts, they are trained in them and live them experientially when they have to work as a team.

Once the protocol, the texts and the sequencing of sessions were created and the teaching staff was prepared, the innovation project was applied in several subjects during a semester, taking into account that the students had a lack in this respect known by previous research and experience.

Once the teaching methodology was finalized, to confirm its relevance and continue replicating the cooperative experience, the students were asked to express their perception on the degree to which they considered that the deployed cooperative teamwork had contributed to developing their Social Competence. The results are presented in this dissertation in order to show the scientific results of this process of qualitative deepening.

The European Higher Education Area (EHEA) proposes the formulation of teaching objectives as learning outcomes, expressed as competences and linked to professional profiles (Cano, 2008). A new training model aimed at improving the ability to respond to social demands and the labor market, addressing the rapid social transformations (Román, Vecina, Usategui, del Valle and Venegas, 2015), globalization (Trujillo and Sánchez, 2013), the impact of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) (Aguaded-Gómez, 2013), knowledge management (Rabadán and Pérez, 2012), as well as management of diversity (Más and Olmos, 2012).

Derived from the field of training and professional management, the concept of competence is inserted in recent years in education in general (European Commission / EACEA / Eurydice, 2015) and adopts a central position in Higher Education. The concept of competence has been subjected to numerous attempts at definition from different disciplines and areas (Mulder, Weigel and Collings, 2008, Ortiz, Vicedo, González and Recino, 2015, Restrepo, 2014). Basic competences are those whose purpose is the integration of ICTs and communication, the promotion of technological culture and foreign languages, as well as the entrepreneurial spirit and social skills (Ferrés, 2007). However, there is no unanimous consensus about what they really are and how they should be understood in university work, regardless of their direct link to the world of work.

In this context, a group of European universities promotes the Tuning Europe Project with the aim of harmonizing the teaching structures in Higher Education. Thus, reference points are determined for the generic and specific competences of each discipline in a series of thematic areas: business studies, education sciences, geology, history, mathematics, physics and chemistry, among others. In this evaluative study we reformulated some generic competences related to social communication, interpersonal and social relationships, associated with the construct Interpersonal Intelligence or Social Competence.

The construct Interpersonal Intelligence is a subtype of Intelligence that is among the eight proposed by Gardner (1985) in his Multiple Intelligences Theory, which Salovey and Mayer (1990) later deepened, until developing the construct Emotional Intelligence. This concept would reach its maximum degree of diffusion and impact with the work of Goleman (2006), who broadens the frame of reference beyond the unipersonal, to delve into the psychology of the relationships that remain with others; Social Intelligence According to Gardner (2005, p.47), “interpersonal intelligence is built from a nuclear capacity to feel distinctions among others: in particular, contrasts in their moods, temperaments, motivations and intentions.” We could say then that a person with an adequate development of their interpersonal intelligence would be able to differentiate the people with whom they relate according to what they express (moods, temperaments, motivations and intentions).

For their part, Bisquerra and Pérez (2007, p. 72) review and update the model around emotional competencies and assimilate Interpersonal Intelligence to Social Competence as “ability to maintain good relationships with other people. This implies mastering social skills: capacity for effective communication, respect, pro-social attitudes, assertiveness, etc.” The importance of Social Competence derives, then, from the continuous contact we have with our peers since our birth. We can even say that we are genetically programmed to interact with other people. Although this predisposition does not guarantee the quality of said relationships. Decety, Norman, Berntson and Cacioppo (2012) state that behaviors related to Empathy, for example, have collaborated in the most primitive homeostatic processes that intervene in reward and pain systems in order to facilitate various processes of social attachment.

These shared emotions can facilitate the empathic concern that promotes pro-social behaviors and altruism. Cooperation, for example, is a fundamental aspect of all biological systems, from bacteria to primates, including humans (Decety, Bartal, Uzefovsky and Knafo-Noam, 2016). Therefore, in all educational stages, including Higher Education, it is necessary to generate learning structures that develop cooperation as an essential aspect for the development of Social Competence. We consider that the structures based on Cooperative Learning are the most appropriate educational strategies to achieve it. García and Troyano (2010, p. 8) support this conviction by stating that: “cooperative learning seeks the collective construction of knowledge and the development of mixed skills -learning and personal and social development-, where each member of the group is responsible for his learning and that of the other members of the group.” With greater precision it can be stated as follows:

Cooperation consists in working together to achieve common goals. In a cooperative situation, individuals seek to obtain results that are beneficial to themselves and to all other members of the group. Cooperative learning is the didactic use of small groups in which students work together to maximize their own learning and that of the others (Johnson, Johnson and Holubec, 1999, p. 5).

For cooperation to really take place, five essential elements are raised (Johnson, Johnson and Holubec, 1999):

Current literature shows that cooperative team learning improves basic social skills to be effective in other similar situations (Del Barco, Felipe, Mendo and Iglesias, 2015), transactional communication and elaboration of one’s own and shared ideas (Jurkowski and Hanze, 2015), attitudes towards learning (Gil, 2015) and global competences (Cebrián-de la Serna, Serrano-Angulo and Ruiz-Torres, 2014), specific and transversal (Oricain, 2015). The superiority of cooperative learning over individual one in the performance of university students and the power and confidence in the work team is evident, therefore (Camilli, 2015, Del Barco, Mendo, Felipe, Polo and Fajardo, 2015).

2. OBJECTIVES

The general objective of this paper is to demonstrate that cooperative work contributes to the development of social competence, which includes a series of fundamental competences for quality social relations in the personal and professional field, as required by the EHEA to respond to the demands of society and the labor market.

3. METHODOLOGY

The Cooperative Teaching Innovation Project we implemented focused on 4 subjects taught by professors who are part of it, in order to ensure its viability and rigor in the approaches. It was developed during the 2015-16 academic year, with a total duration of 6 months, structured in weekly sessions of 2 hours. The tasks performed were eminently practical: preparation of activity protocols, design of process systems and routines or preparation of resources and teaching materials. The execution of the tasks in the respective subjects consisted in converting the theoretical content into practical productions of them. The common methodological layout for all of them was inspired by the Arnaiz and Linares model (2010):

So as to collect the students’ perception, an applied research procedure was designed (Gast and Ledford, 2014), from a qualitative non-experimental perspective, framed in the field of evaluation of results for decision making and focused on the evaluation of the acceptance and satisfaction of the target population (Mertens, 2014).

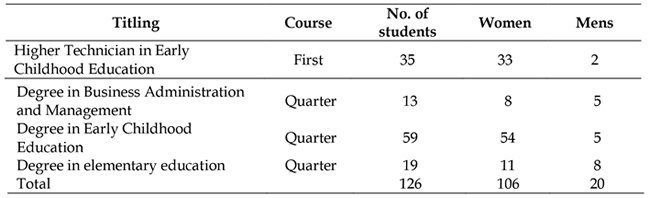

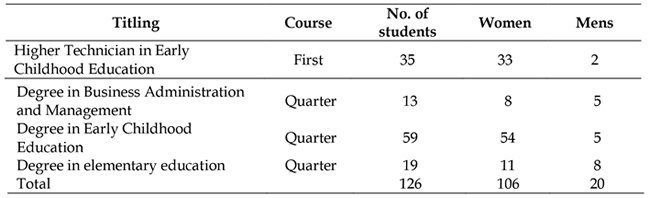

The sample was composed of students who participated in the applied Cooperative Teaching Innovation Project; 126 first and fourth-year students, in the form of face-to-face study, of the Degrees in Infant Education, Primary Education and Administration and Business Management, as well as the Higher Degree Training Cycle of Early Childhood Education, of an institution of Higher Education of private ownership, with ages from 18 to 25 years and a representation of 84% of the female gender and 16% of the male gender (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample composition.

Source: own elaboration.

In order to collect the perception of students, regarding cooperative teamwork as a work strategy that contributes to the development of their Social Competence, a questionnaire was used, prepared ad hoc by the researcher professors participating in the Teaching Innovation Project. Thus, it poses 41 questions to be answered using a Likert rating scale, with 5 response options and a range of frequencies where 1 equals almost never / cannot be seen clearly and 5 almost always. The questionnaire required to indicate to the respondent how often he considers that Cooperative Learning develops capacities, abilities and competences emerging to the performance of the Social Competence: Empathy, Consensus or Democratic Participation and Assertiveness. Its completion was voluntary, anonymous. Although the total population under study was 264 students, the questionnaire finally covers 47.7 %, which projects a sample of 126, with a confidence level of 95%, 50% heterogeneity and a confidence interval of 6.3%. Its distribution was made digitally, from the respective Virtual Classrooms of the Virtual Campus of the University Institution, inserting an access link from the Ads section. The support technology for the questionnaires was provided by Google Forms.

The reliability of the questions was checked from Cronbach alpha internal consistency ratio, obtaining a general value of 0.963, considered highly reliable (Cohen, Manion and Morrison, 2013). Both the questions and the structure and items used in the questionnaire were validated by experts in disciplines related to the subject matter of the study. Likewise, the previous publications of the members of the research team were taken into account (Parra and Peña, 2012, Peña, Díez and García, 2012, Peña and Parra, 2011), as well as authors and reference works in relation to the theoretical framework that supports the study in the subject matter we dealt with (Bisquerra and Pérez, 2007, Gardner, 2005, Goleman, 1995, Goleman, 2006, Salovey and Mayer, 1990). The treatment of the collected information was carried out through statistical analysis of quantitative data based on frequencies, using the statistical package IBM SSPS Statistics 21.

4. DISCUSSION

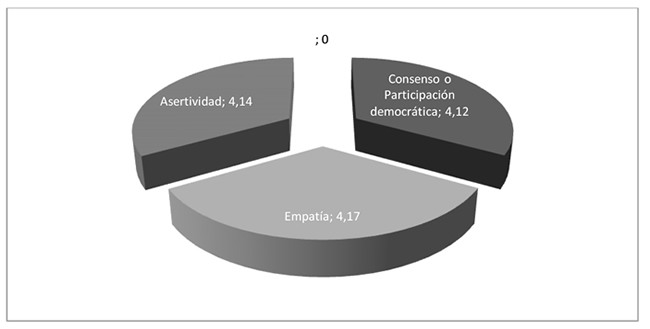

As can be seen in Figure 1, the result of the analysis shows a very positive perception about the degree to which they consider that cooperative teamwork contributes to developing Social Competence. The scores are very similar in all capacities: Empathy, Consensus or Democratic Participation and Assertiveness.

Source: own elaboration.

Figure 1. Student global scores.

The total average score of the items included in them (considering a score scale of 1 to 5) are above

4.1. With an average standard deviation of 0.9

In general, students perceive that Cooperative Learning contributes very often (according to its equivalence with the nominal scale we used) to contribute to developing Social Competence. Among them, those related to Empathy stand out, with a score of 4.17. On the contrary, the set of skills related to the capacity of Consensus or Democratic Participation is granted a lower score, although the difference between the two capacities is not significant; 4.12. The capacity for Assertiveness is in an intermediate position, with an average score of 4.14. Below are the results obtained for each specific skill that is collected for each studied capacity.

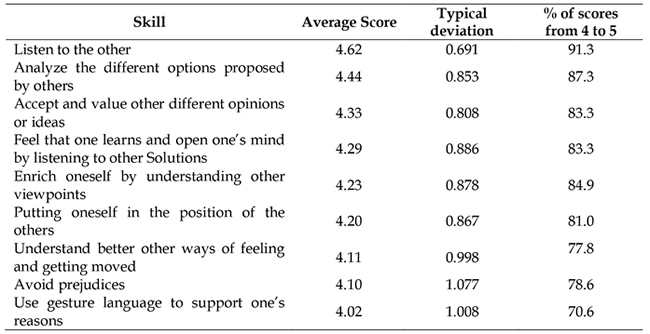

a) Empathy Capacity

This capacity includes the best valued skill of all those studied in this piece of research: Listening to the other, with a frequency of 4.6, which brings it closer to the nominal value: Almost always. This means that more than 91% of students have scored a 4 or 5. On the opposite side we find, but with little difference: Use gestural language to support arguments, with a score of 4.02, closer to the face value: Very often. This represents 70.6% of students who score it with a 4 or 5. The assessment that students make about the frequency with which Cooperative Learning allows them to develop the rest of skills associated with Empathy, ordered from highest to lowest score, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Contribution of cooperative learning to the development of empathy-related skills.

Source: own elaboration.

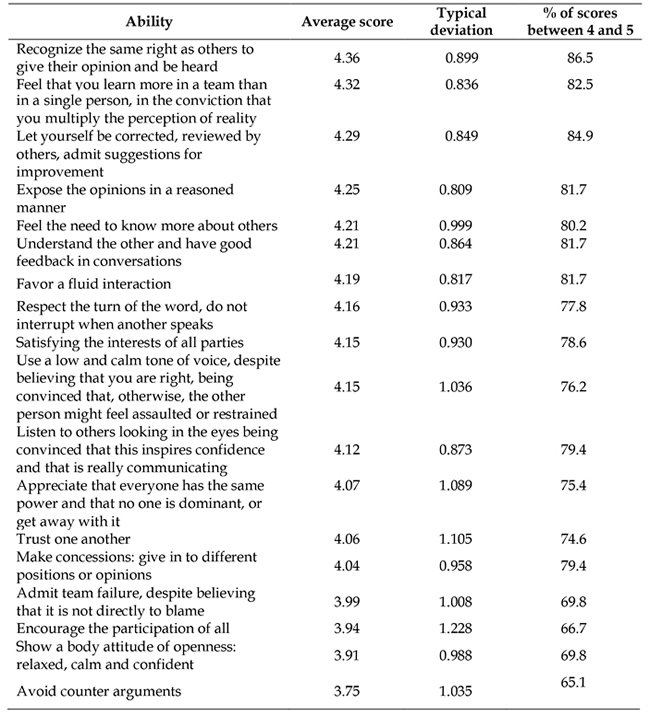

b) Capacity for Consensus or Democratic Participation

The capacity for Consensus or Democratic Participation contains the worst scored ability of all which are asked in this piece of research: Avoid counteracting arguments, with a frequency of 3.7 that attributes the nominal value: Frequently. This means that 65% of students attribute a score from 4 to 5 as a general trend. This contrasts, with a certain degree of difference, with the ability to: Recognize the same right as others to express their opinion and be heard, which is given a score of 4.36, which approximates it to the nominal value: Very often. Thus, more than 86% of students score it with a 4 or 5. As established for the ability of Empathy, the distribution of the estimates that students make about the frequency with which Cooperative Learning allows them to develop the rest of the skills associated with Consensus or Democratic Participation, in ascending order, are shown in Table.

Table 3. Contribution of cooperative learning to the development of skills associated with consensus or democratic participation.

Source: own elaboration.

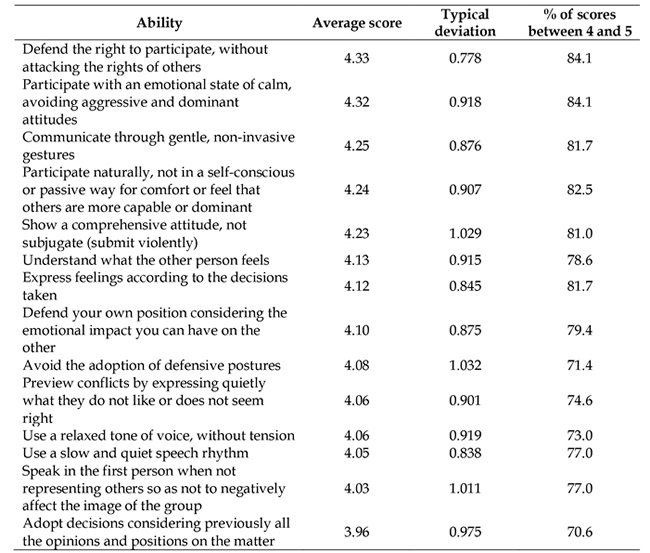

c) Capacity for assertiveness

The skills related to the capacity for Assertiveness maintain a very similar average score, they do not contain any extreme value within the global computation of the studied competences, as it happens with the two previous capacities. However, as done previously, we can point out, within this same dimension, as the best valued skill: Defend the right to participate, without attacking the rights of others, with a frequency of 4.33, so it is associated with the nominal value: Almost always. It means, then, that a little more than 84% of students have scored it with a 4 or a 5. The furthest skill from this score is: Adopt decisions previously considering all the opinions and positions about it, with a score of 3.96, which relates it to the nominal value: Frequently. It is a little more than 70% of students who score it with a 4 or 5. The rest of abilities related to the capacity of Assertiveness are arranged in Table 4.

Table 4. Contribution of cooperative learning to the development of skills associated with assertiveness.

Source: own elaboration.

The obtained results can be framed in the line of recent research that highlights Cooperative Learning in Higher Education as a methodological proposal that reports benefits to the students and allows them to develop, among other things, their Social Competence (Lanza and Fernández, 2012). This is also demonstrated in experimental works carried out from various academic disciplines, with significant improvements being observed in the respective experimental groups, in the levels of competence perception, self-determined motivation and social relations (Fernández-Río, Cecchini and Méndez-Giménez, 2014), as well as self-confidence and anxiety reduction (Berger and Hanze, 2015; Kwok and Lau, 2015; Partridge and Eamoraphan, 2015). It also occurs in specific capacities included in this evaluative study such as Empathy (Lirola, 2015, Rodríguez, Trianes and Casado, 2013), Consensus or Democratic Participation and skills related to Assertiveness (Durán-Aponte and Durán-García, 2013; Huang, Wu and Hwang, 2015; Jauregi, Vidales, Casares and Fuente, 2014). Likewise, the benefits of Cooperative Learning are supported by the latest findings of social neuroscience (Clark and Dumas, 2015, Necka, Cacioppo and Cacioppo, 2015).

This evaluative study provides novelty in that it explores a sample of students with different profiles, using the variables Assertiveness, Consensus or Democratic Participation and Empathy as a starting point, and on the perception that the students themselves express explicitly. This way it is confirmed that students perceive that, through Cooperative Learning, their Social Competence is developed and, therefore, it is assumed that they value this type of methodological strategy very positively to achieve it. The best valued skills are those that relate to the cognitive field and other emotional, axiological and paradigmatic skills related to alterity, the value of justice, sharing and recognition of the right of participation are relegated to a second position, although with little difference. Listening to the other, recognizing the same right that others have to participate, give opinions and be heard become the skills best valued by students with a cognitive orientation, to the detriment of others more related to the emotional sphere; body, attitudinal and paradigmatic language,: use gestural language to support the arguments put forward, avoid counteracting arguments and adopt decisions previously considering all opinions and positions on the subject.

5. CONCLUSIONS

After conducting a participant observation for years (2009-2013), conducting a participatory action research in an academic year (2013-2014) and carrying out an educational innovation project on cooperative work, we estimate that qualitative research that combines several techniques and tools for years in Higher Education on the same subject is very effective and ensures the adequacy to the diversity of students.

We want to highlight, in this case, the structuring of the participatory action in the pilot project to create a project of educational innovation with more scope as very adequate to deepen the reality and provide variables as a starting point both for the innovation project and for a research project. The advantages of participatory action research that we list are many. First, it provides the professor with research tools and teaching improvement because it deepens, adapts it to the reality of the classroom that the professor guides and allows him to understand the needs of the students. Second, it is a human environment favoring a climate that allows students to express themselves about their learning process, which stimulates them and also favors extroversion with their classmates, as well as other factors such as conflict management, greater mutual knowledge and understanding. Third, it facilitates that the student understands the research of the teaching staff in Education, both of the project and of the used techniques, as well as of the attitude of humility of the professor who seeks to understand the students in order to deploy suitable teaching methodologies.

With regard to the results of the qualitative research and the innovation project, we can finally conclude that it is pertinent to replicate the experience and continue with the use of Cooperative Learning. On the other hand, the measures that could counteract the impact of the possible limitations of this evaluative study on the obtained results are: Increase the sample size in order to generalize the obtained results further, increase the duration of the study to assess the degree of attrition in the participating agents due to the fatigue generated by the work dynamics in longer periods of intervention than the one we used and examine the factors that could hinder the participation of the students in Cooperative Learning (Lanza, 2015; Shimazoe and Aldrich , 2010).

The obtained results encourage us to continue with the research line initiated while raising new questions. Some future lines of work are: expand the contexts of implementation of Cooperative Learning and analyze the differences in their results. Include the strategies of cooperative learning in subjects so far oriented to the lecture and assess differences in the results on the suitability of the methodology for larger classrooms oriented to the lectures, adapt the methodology of Cooperative Learning to incorporate it into the modality of communication through ICTs (Salmerón, Rodríguez and Gutiérrez, 2010) and include, in the strategies we used, the findings of social neurosciences related to social competence; empathy and prosocial behaviors (Necka et al., 2015).

REFERENCES

1. Aguaded, I. (2013). El Programa «Media» de la Comisión Europea, apoyo internacional a la educación en medios [Media Programme (EU) - International Support for Media Education]. Comunicar, 40(20), 7-8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-01-01

2. Arnaiz, P. y Linares, J. E. (2010). Proyecto ACOOP. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia y Consejería de Educación, Formación y Empleo.

3. Berger, R. y Hanze, M. (2015). Impact of expert teaching quality on novice academic performance in the jigsaw cooperative learning method. International Journal of Science Education, 37(2), 294-320. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2014.985757

4. Bisquerra, R. y Escoda, N. P. (2007). Las competencias emocionales, Educación XX1, 10, 61-82. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.1.10.297

5. Camilli, C. (2015). Aprendizaje cooperativo e individual en el rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios: un meta-análisis, (Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid). Disponible en http://eprints.ucm.es/30997/

6. Cano, M. E. (2008). La evaluación por competencias en la educación superior. Profesorado. Revista de currículum y formación del profesorado, 12(3), 1-16.

7. Cebrián-De La Serna, M., Serrano-Angulo, J., y Ruiz-Torres, M. (2014). Las eRúbricas en la evaluación cooperativa del aprendizaje en la Universidad [eRubrics in Cooperative Assessment of Learning at University]. Comunicar, 43(22), 153-161. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-15

8. Clark, I. y Dumas, G. (2015). Toward a neural basis for peer-interaction: what makes peer-learning tick? Frontiers in psychology, 6, 1-12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00028

9. Cohen, L., Manion, L. y Morrison, K. (2013). Research methods in education. London y New York: Routledge.

10. Decety, J., Norman, G. J., Berntson, G. G. y Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). A neurobehavioral evolutionary perspective on the mechanisms underlying empathy. Progress in neurobiology, 98(1), 38-48. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.05.001

11. Decety, J., Bartal, I. B. A., Uzefovsky, F. y Knafo-Noam, A. (2016). Empathy as a driver of prosocial behaviour: highly conserved neurobehavioural mechanisms across species. Phil. Trans. R. Soc., 371(1686), 1-11. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0077

12. Del Barco, B. L., Felipe, E., Mendo, S. y Iglesias, D. (2015). Habilidades sociales en equipos de aprendizaje cooperativo en el contexto universitario, Psicología conductual. Revista internacional de psicología clínica y de la salud, 23(2), 191-214.

13. Del Barco, B. L., Mendo, S., Felipe, E., Polo, M. I. y Fajardo, F. (2015). Team Potency and Cooperative Learning in the University Setting. Journal of Psychodidactics, 21(2), 1-15. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1387/RevPsicodidact.14213

14. Durán-Aponte, E. y Durán-García, M. (2013). Aprendizaje cooperativo en la Enseñanza de Termodinámica: Estilos de Aprendizaje y Atribuciones Causales. Journal of Learning Styles, 6(11), 256-275.

15. European Commission/Eacea/Eurydice (2015). The European Higher Education Area in 2015: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi: 10.2797/128576

16. Fernández-Río, J., Cecchini, J.A. y Méndez-Giménez, A. (2014). Effects of cooperative learning on perceived competence, motivation, social goals, effort and boredom in prospective Primary Education teachers, Infancia y Aprendizaje: Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 37(1), 57-89. doi: 10.1080/02103702.2014.881650

17. Ferrés, J. (2007). La competencia en comunicación audiovisual: dimensiones e indicadores, Comunicar, 29(15), 100-107.

18. García, A. y Troyano, Y. (2010). Aprendizaje cooperativo en personas mayores universitarias. Revista Interamericana de Educación de Adultos, 32(1), 7-21.

19. Gardner, H. (2005). Inteligencias múltiples. La teoría en la práctica. Barcelona: Paidós.

20. Gast, D. L. y Ledford, J. R. (2014). Applied research in education and behavioral sciences. Single Case Research Methodology: Applications in Special Education and Behavioral Sciences. New York y London: Routledge.

21. Gil, P. (2015). Percepciones hacia el aprendizaje cooperativo del alumnado del Máster de Formación del Profesorado de Secundaria. REDU. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 13(3), 125-146.

22. Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

23. Goleman, D. (2006). Inteligencia social: la nueva ciencia de las relaciones humanas. Barcelona: Kairós.

24. Huang, Y. H., Wu, P. H. y Hwang, G. J. (2015, July). The Pilot Study of the Cooperative Learning Interactive Model in e-Classroom towards Students’ Learning Behaviors”. In T. Matsuo, K. Hashimoto, T. Mine y S. Hirokawa (Eds.), Advanced Applied Informatics (IIAI-AAI), 2015 IIAI 4th International Congress on. Okayama: CPS, pp. 279-282. doi: 10.1109/IIAI-AAI.2015.193

25. Jauregi, P. A., Vidales, K. B., Casares, S. M. G. y Fuente, A.V. (2014). Estudio de caso y aprendizaje cooperativo en la universidad. Profesorado: Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 18(1), 413-429.

26. Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T. y Holubec, E. J. (1999). El aprendizaje cooperativo en el aula. Barcelona: Paidós.

27. Jurkowski, S. y Hanze, M. (2015). How to increase the benefits of cooperation: Effects of training in transactive communication on cooperative learning, British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 357–371. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12077

28. Kwok, A. P. y Lau, A. (2015). An Exploratory Study on Using the Think-Pair-Share Cooperative Learning Strategy. Journal of Mathematical Sciences, 2, 22-28.

29. Lanza, D. y Fernández, A. B. (2012). Aprendizaje cooperativo como fórmula para el desarrollo de competencias en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior: un estudio exploratorio con alumnos de Psicología de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Revista del Congrés Internacional de Docència Universitària i Innovació (CIDUI), 1(1).

30. Lanza, D. (2015). Aprendizaje cooperativo en el espacio europeo de educación superior: debilidades y fortalezas de una metodología didáctica, Revista del Congrés Internacional de Docència Universitària i Innovació (CIDUI), 2, 1-14.

31. Lirola, M. M. (2015). The Potential of Cooperative Learning and Peace Education to Promote the Acquisition of Social Competences at Tertiary Education, International Journal of Peace, Education and Development, 3(1), 37-47.

32. Mertens, D. M. (2014). Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods. Thousands Oaks: Sage Publications.

33. Mulder, M., Weigel, T. y Collings, K. (2008). El concepto de competencia en el desarrollo de la educación y formación profesional en determinados países, miembros de la UE. Profesorado: Revista de curriculum y formación del profesorado, 12(3), 1-26.

34. Necka, E. A., Cacioppo, S. y Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Social Neuroscience of the Twenty-First Century, International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(22), 485–488. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.56020-6

35. Oricain, N. D. (2015). Adquisición de competencias en el marco del Aprendizaje Cooperativo: valoración de los estudiantes, REDU: Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 13(1), 339-359.

36. Ortiz, M., Vicedo, A., González, S. y Recino, U. (2015). Las múltiples definiciones del término «competencia» y la aplicabilidad de su enfoque en ciencias médicas, Edumecentro, 7(3), 20-31.

37. Parra, M. C. y Peña, B. (2012). El aprendizaje cooperativo mediante actividades participativas, Revista Anales de la Universidad Metropolitana, 12(2), 15-37.

38. Partridge, B. J. y Eamoraphan, S. (2015). A comparative study on students’foreign language classroom anxiety through cooperative learning on grade 10 students at Saint Joseph Bangna School, Thailand. Scholar, 7(1), 171-185.

39. Peña, B. y Parra, M. C. (2011). Aprendizaje cooperativo en observación sistemática mediante el visionado de films. Revista Vivat Academia, 117E, pp. 701-712. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15178/va.2011.117E.701-712

40. Peña, B., Díez, M. y García, M. (2012). La conveniencia de la inteligencia emocional por parte de los maestros de infantil y primaria En B. Peña (Coord.), Desarrollo humano, 15-48. Madrid: Visión libros.

41. Peña, B. (2014). Evaluación mediante la observación participante de una metodología de trabajo en equipo para el desarrollo de competencias básicas de inteligencia social. En González J. J., Sánchez, F. J. y Castejón M. A. Innovación Evaluación y Universidad, 46-60. Murcia: UCAM.

42. Rabadán, J. A. y Pérez, E. (2012). Renovación pedagógica en la sociedad del conocimiento, Nuevos retos para el profesorado universitario. RED-DUSC. Revista de Educación a Distancia-Docencia Universitaria en la Sociedad del Conocimiento, (6), 1-11.

43. Restrepo, J. A. (2014). La argumentación de las competencias en educación superior, ¿conducen a emulación o a generar virtud? No siempre el saber hacer implica el saber ser. Revista Interamericana de Investigación, Educación y Pedagogía, RIIEP, 7(2), 235-250.

44. Rodríguez, F. M. M., Trianes, M. V. y Casado, A. M. (2013). Eficacia de un programa para fomentar la adquisición de competencias solidarias en estudiantes universitarios, European Journal of Education and Psychology, 6(2), 95-104.

45. Román, S. S., Vecina, C., Usategui, E., Del Valle, A. I. y Venegas, M. (2015). Social representations and educational guidance of the professorship, Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23, 1-18. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v23.2088

46. Salovey, P. y Mayer, J.D. (1990). Emotional intelligence, Imagination, cognition and personality, 9(3), 185-211.

47. Salmerón, H., Rodríguez, S. y Gutiérrez, C. (2010). Metodologías que optimizan la comunicación en entornos de aprendizaje virtual, Comunicar, 34(17), 163-171. doi: 10.3916/C34-2010-03-16

48. Shimazoe, J. y Aldrich, H. (2010). Group work can be gratifying: Understanding and overcoming resistance to cooperative learning, College Teaching, 58, 52-57.

49. Más, O. y Olmos, P. (2012). La atención a la diversidad en la educación superior: una perspectiva desde las competencias docentes, Revista de Educación Inclusiva, 5(1), 159-174.

50. Trujillo, A. L. y Sánchez, M. T. (2013). Apuntes sobre la internacionalización y la globalización en educación: de la internacionalización de los modelos educativos a un nuevo modelo de gobernanza, Journal of Supranational Policies of Education, (1), 53-66.

AUTHORS

Francisco José Sánchez Marín: Doctor in Pedagogy and Master in Health Law and Bioethics. Professor Contracted Doctor in the San Antonio Catholic University of Murcia (UCAM). He has participated in projects related to Education and Technologies of Information and Communication, Diversity, Inclusion, Autonomous Student Work, Digital Competences and Good Practices in the framework of the EHEA, Innovation in teaching methodology and evaluation of learning. His lines of research include: values and education, inclusive school, school organization and management, continuing education of teachers, technologies applied to education, attention to diversity and educational methods.

fjsanchez235@ucam.edu

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3164-6333Google Scholar: https://goo.gl/8HQETY

ResearchID: http://www.researcherid.com/rid/L-8164-2014

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Francisco_Sanchez_Marin

María Concepción Parra Meroño: PhD in Business Administration and Management: Marketing and Organization. She is a professor in the Degree in Business Administration and in the Master in Marketing and Communication and in the Master MBA of the UCAM. His main lines of research are educational innovation, consumer behavior, marketing and communication. He has published in impact journals such as Estudios sobre Educación, Historia y Comunicación Social, Revista Opción, Cuadernos de Economía y Direccion de la Empresa, Journal of Knowledge Management. He has published in prestigious editorials (SPI ranking) such as Tecnos, McGrawHill, UOC or Pirámide.

mcparra@ucam.edu

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0457-4613Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=H49mMdgAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria_Concepcion_Parra

Beatriz Peña Acuña: He has participated in national and international congresses and has published in impact journals, as well as in prestigious editorials. Accredited Full Professor Extraordinary doctorate prize Principal researcher of the Personal Development group. His main lines of research are educational innovation and communication. He has published in impact journals such as Studies on Education, History and Social Communication, Chasqui, Opción Magazine and books in SPI rankings such as Tecnos, McGrawHill, Dykinson, Cambridge scholar publishing, MediaXXI.

bpena@ucam.edu

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2577-5681

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=-yTRm0cAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchID: http://www.researcherid.com/rid/L-9229-2014

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Beatriz_Pena-Acuna

Academia.edu: http://ucam.academia.edu/BeatrizPe%C3%B1aAcu%C3%B1a

Mendeley: https://www.mendeley.com/profiles/beatriz-pena-acuna/