doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.138.96-119

RESEARCH

THE MELODRAMATIC TRAITS OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS IN PEDRO ALMODÓVAR: STUDY OF CHARACTERS OF THE LAW OF DESIRE, HIGH HEELS AND THE FLOWER OF MY SECRET

LOS RASGOS MELODRAMÁTICOS DE TENNESSEE WILLIAMS EN PEDRO ALMODÓVAR: ESTUDIO DE PERSONAJES DE LA LEY DEL DESEO, TACONES LEJANOS Y LA FLOR DE MI SECRETO

OS TRAÇOS MELODRAMÁTICOS DE TENNESSEE WILLIAMS EM PEDRO ALMODÓVAR: ESTUDO DE PERSONAGENS DA LA LEY DEL DESEO, TACONES LEJANOS E LA FLOR DE MI SECRETO

Valeriano Durán Manso1 He is professor in the Department of Marketing and Communication of the University of Cadiz, Doctor by the University of Seville and Bachelor in Journalism by the same University. He is a researcher of the Research Group on Analysis of Media, Images and Audiovisual Stories (ADMIRA) of the Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising of the University of Seville. His lines of research are based on the Tennessee Williams film adaptations, the construction and analysis of the audiovisual character, the history of universal cinema, the history of Spanish cinema, and the didactic possibilities of the history of cinema in the history of the education. http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9188-6166

1University of Cádiz, Spain

ABSTRACT

The main film adaptations of the literary production of the American playwright Tennessee Williams premiered in 1950 through 1968, and they settled in the melodrama. These films contributed to the thematic evolution of Hollywood due to the gradual dissolution of the Hays Code of censorship and, furthermore, they determined the path of this genre toward more passionate and sordid aspects. Thus, A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, or Suddenly, Last Summer incorporated sexual or psychological issues through tormented characters that had not been previously dealt with in the cinema. The classic Hollywood melodrama has had a remarkable influence in the filmography of Pedro Almodóvar, and the best evidence is the tendency of the director from La Mancha to deal with this genre in his complex plots. In addition, the tormented characters starring in them contain many personal, family or sexual traits which are very present in the main characters of the southern playwright. From these considerations, this paper aims to reflect on the presence of the melodramatic traits of the adaptations of Williams in Almodóvar by analyzing, as a person and as a role, the main characters of his three films belonging to this genre: The Law of Desire, High Heels y The Flower of My Secret.

KEY WORDS: Analysis of characters, Melodrama, Tennessee Williams, Pedro Almodóvar, The Law of Desire, High Heels, The Flower of My Secret

RESUMEN

Las principales adaptaciones cinematográficas de la producción literaria del dramaturgo norteamericano Tennessee Williams se estrenaron entre 1950 y 1968 y se asentaron en el melodrama. Estas películas contribuyeron a la evolución temática de Hollywood debido a la paulatina disolución del Código Hays de censura y, además, determinaron el camino de este género hacia aspectos más pasionales y sórdidos. Así, Un tranvía llamado deseo, La gata sobre el tejado de zinc, o De repente… el último verano incorporaron temas de carácter sexual o psicológico mediante unos personajes atormentados que no habían sido tratados anteriormente en el cine. El melodrama clásico de Hollywood ha tenido una notable influencia en la filmografía de Pedro Almodóvar, y prueba de ello es la tendencia del director manchego por abordar este género en sus complejas tramas. Además, los atormentados seres de ficción que las protagonizan contienen una serie de aspectos personales, familiares, o sexuales que están muy presentes en los protagonistas del dramaturgo sueño. Desde estas consideraciones, este trabajo pretende reflexionar sobre la presencia de los rasgos melodramáticos de las adaptaciones de Williams en Almodóvar mediante el análisis como persona y como rol de los personajes principales de sus tres películas que mejor se enmarcan en este género: La ley del deseo, Tacones lejanos y La flor de mi secreto.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Análisis de personajes, Melodrama, Tennessee Williams, Pedro Almodóvar, La ley del deseo, Tacones lejanos, La flor de mi secreto

RESUMO

As principais adaptações cinematográficas da produção literária do dramaturgo norte americano Tennessee Williams estrearam entre 1950 - 1968 e assentaram no melodrama. Esses filmes contribuíram a evolução temática de Hollywood devido à paulatina dissolução do código Hays de censura e, ademais, determinaram o caminho deste gênero em direção aos aspectos mais passionais e sórdidos. Assim, “Un tranvia llamado deseo”, “La gata sobre El tejado de zinc”, ou “De repente... El último verano” incorporaram temas de caráter sexual ou psicológico mediante uns personagens atormentados que não haviam sido tratados anteriormente no cinema. O melodrama clássico de Hollywood teve uma notável influência na filmografia de Pedro Almodóvar, e prova disso é a tendência do diretor espanhol por abordar esse gênero em suas complexas tramas. Além disso , os atormentados seres de ficção que protagonizam , contém uma série de aspectos pessoais, familiares ou sexuais que estão muito presentes nos protagonistas do dramaturgo. Desde essas considerações, este trabalho pretende reflexionar sobre a presença dos traços melodramáticos das adaptações de Williams em Almodóvar mediante a análise como pessoa e como rol dos personagens principais de seus três filmes que melhor se enquadram neste gênero: “La ley del deseo”, “Tacones lejanos” e “La flor de mi secreto”.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Analises dos personagens, Melodrama, Tennessee Williams, Pedro Almodóvar, Tacones lejanos, La ley del deseo, La flor de mi secreto

Received: 11/06/2016

Accepted: 04/12/2016

Published: 15/03/2017

Correspondence: Valeriano Durán Manso. valeriano.duran@uca.es

1. INTRODUCTION

The American playwright Tennessee Williams (Columbus, Mississippi, 1911-New York, 1983) had a privileged place in the scenic area of Broadway from the premiere of The Glass Menagerie in 1944, but he also influenced the Hollywood change in the later decade. His tendency to address issues of a sexual kind and build characters of great psychological complexity caused a great impact on the premiere of his works, and aroused the interest of the film industry. Although the Hays Code prevailed here since 1934 and Williams’s statements largely violated the guidelines of this sensor apparatus, from 1950 to 1968 the major film adaptations of his texts were released. These films provided the thematic openness and contributed to the development of melodrama to add to the romantic trend of the genre an oppressive atmosphere, fictional beings who are victims of unfavorable circumstances, and some issues like adultery, nymphomania, homosexuality, drug addiction or abortion; present in American society but hidden due to moral questions. Some of them such as A Streetcar Named Desire, Elia Kazan, 1951, Baby Doll, Elia Kazan, 1956, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Richard Brooks, 1958, Suddenly Last Summer, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1959, Sweet Bird of Youth, Richard Brooks, 1962, or The Night of the Iguana, John Huston, 1964 made it possible the dissolution of the code in 1967 and became a reference of a genre that in these years committed itself to more passionate and sordid issues.

Because of the tendency of Pedro Almodóvar (Calzada de Calatrava, Ciudad Real, 1949) to draw inspiration from the classical Hollywood cinema (Perales, 2008), his filmography is built on genres as solid as comedy, melodrama, or suspense. As says Roman Gubern, the intertextuality of the filmmaker gives rise to “a bold hybridization of genres and an ironic mannerism in their reinterpretations of the great themes of Douglas Sirk or Vincente Minnelli, but released from Protestant normativism that has corseted moviemaking in Hollywood” (Zurián and Vazquez, 2005, p. 50-51). Therefore, melodrama has a prominent place in his film work because of the issues he addresses, where family, love and sex occupy a prominent place, such as the characters he builds, mostly dominated by their passionate instincts. In this regard, “it is necessary to emphasize the admiration of Almodóvar for Tennessee Williams, particularly for the dramas featuring female characters who are in extreme emotional situations” (Rodríguez, 2004, p. 140).

Almodóvar’s films that are best framed in the classic American melodrama are those that have a greater similarity to the main titles of the genre, and especially to those of Williams. Thus, Law of Desire (1987) High Heels (1991) and The Flower of My Secret (1995), where the passion between a homosexual couple to death, the conflict between a charismatic mother and a shadowy daughter, and the vital and professional crisis of a mature woman are addressed, respectively, are closely related to Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The glass Menagerie (Irving Rapper, 1950) or The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (Jose Quintero, 1961). In this sense, these characters created by Almodóvar have a certain influence of Williams’s, who “are misunderstood who do not conform to conventional family rules, with serious problems of identity and experience daily failure, characteristics that make them unhappy” (Duran Manso, 2011, p. 39). Although Almodóvar has resorted to melodrama in later films like All about My Mother (1999), where there is a direct reference to A Streetcar Named Desire-Talk to Her (2002) and Juliet (2016), those that keep a closer link with Williams at the thematic and character levels are those mentioned above for their classic character. Therefore, the protagonists of these films are studied in this article as prototypes that define Williams’s and then they are analyzed as a person and as a role to better understand their operation in the story.

2. OBJECTIVES

The overall objective of this study is to demonstrate and reflect on those features of Williams’s universe that are more present in Almodóvar with respect to classic Hollywood melodrama and character building. We seek to draw a parallel between two of the most representative authors of the film genre that is closer to real life, and belong to two distinct and distant but similar and close times for being engaged in a process of change and maturation: American society of the decades of the fifties and sixties and Spanish eighties and nineties. Thus, the following specific objectives are established:

–To describe the context in which the film adaptations of Tennessee Williams were released and to value his contributions to the renovation of classic American melodrama.

–To specify the type of fictional beings of Williams and male and female prototypes.

–To highlight the influence of Hollywood melodrama and the films of Williams in Pedro Almodóvar.

–To define how the main characters of Law of Desire, High Heels and The Flower of My Secret are constructed according to of the archetypes of Williams.

3. METHODOLOGY

The study of the political, historical and social context in which the film adaptations of Tennessee Williams premiered helps to understand his relevance in a cinematic framework dominated by the Hays Code, which stipulated what the big screen could show under a Catholic and excessively Puritan approach, the rise of television and the crisis of the studio system. Thus, Hollywood in the late forties was in need of films that talked about topics of everyday life, problems of American society, and also on specific aspects of reality that the code prohibited as drug addiction, adultery or homosexuality (Duran Manso, 2015a; 2015b). The need for change producers and filmmakers longed for made it possible in the fifties a series of films based largely on the successes of Broadway at the time, those films were starred by characters of high drama that came from their own society. Williams, along with Arthur Miller and William Inge, became one of the most represented writers on the big screen thanks to issues with strong psychological content and their tormented characters. The analysis of this context is interesting in order to know how the adaptations of the southern playwright helped the gradual weakening of the Hays Code and how, in turn, they renewed the classic Hollywood melodrama with the addition of seedier and more passionate elements in his characters.

For the development of this work, we used a methodology based on a literary and film analysis of the film adaptations of Tennessee Williams, with special attention to the construction of his characters. This study has allowed a typology of fictional beings of this playwright based on parameters such as social status, physical appearance, age, character, or sexuality, among other things, in order to group them according to those features that determine their personal nature and growth within the story . Being melodramas, the psychology of these characters plays a major role in the development of action and, in most cases, they have even greater relevance than the issues addressed in own works and movies they star. In this regard, it is appropriate to note the words of Diez (2006) on the importance of fictional beings in the story: “The character is a set of psychological, sociological and biophysical features that make him living, unpredictable, surprising and able to change “(p. 170). In this regard, Seger (2000) notes that “the same way in which the creation of a character entails providing them with external characteristics such as physical appearance and behavior, it also implies that the writer must understand the inner world of the character, ie , psychology “(p. 65). Also, we proceeded to extract a male and a female prototype, following the typology of fictional beings that is dealt with, in order to clarify, specify and better define the nature, potential and the impact of the characters created by Williams. Because of the significant influence of the classic American cinema and, in particular, melodrama on post-modern filmmakers and determinants in the current film scene, such as Pedro Almodóvar, we can pose a parallelism between the claustrophobic and rupturistic universe of Tennessee Williams and that of the director from La Mancha. The melodramas of them both feature classic and own gender issues such as excessive passion that ends in tragedy, impossible relationships between parents and children or the loneliness of the mature woman, but stand and agree to contribute some complex characters very close to real life who entail a new twist to that style. Thus, “what matters is to turn the character into something tendentiously real: whether the character is meant to be considered primarily a “psychological unity” or is to be dealt with as a “unit of action’’, the aim is to constitute “a perfect simulation of that which we face in life” (Casetti & Di Chio, 2007, p. 159). Almodóvar’s films that are analyzed are those that are inserted in classic melodrama and also coincide with narrative approaches to adaptations of Williams. Thus, it is intended to compare the themes and characters present in Law of Desire, High Heels and The Flower of My Secret with those in Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Glass Menagerie, Suddenly ... Last Summer , A Streetcar Named Desire or the Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, following the typology of characters and the proposed prototypes.

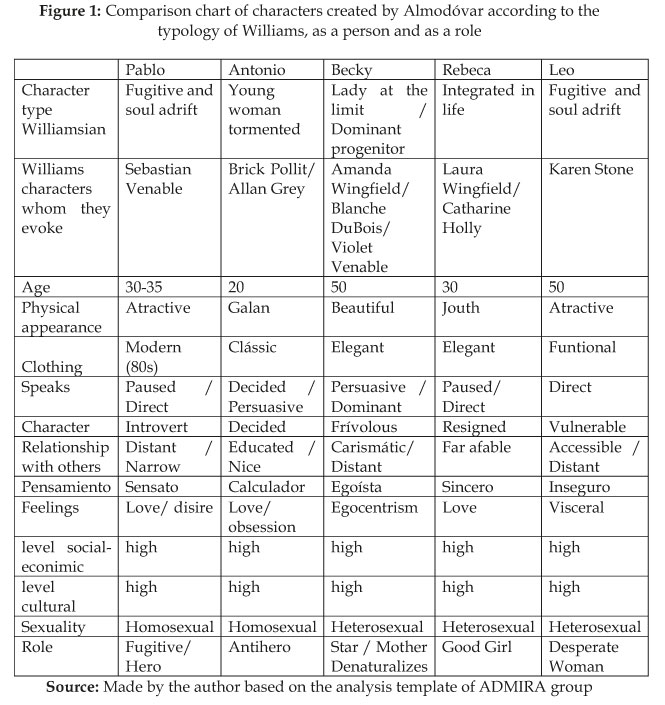

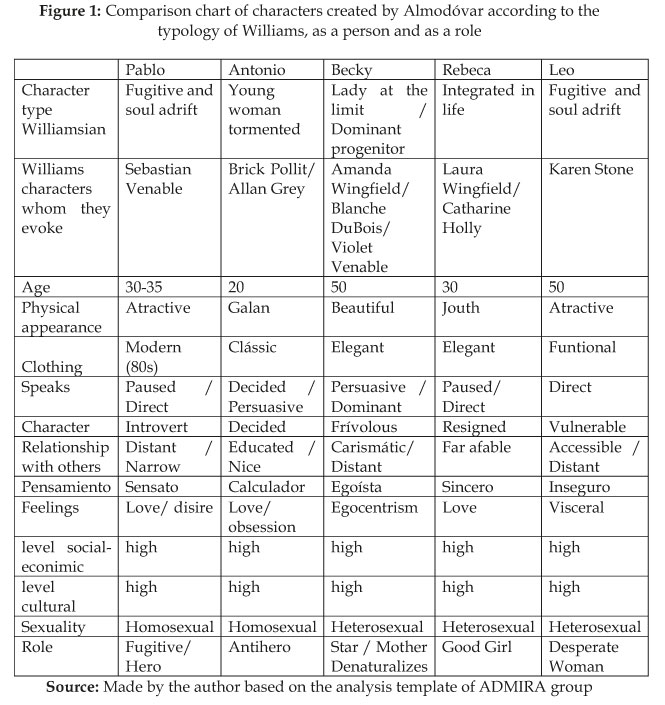

Viewing these films allows you to set the thematic similarities between both authors and the aesthetic differences proper to the different times when they were shot, such as Hollywood after World War II and the post-democratic transition in Spain. Therefore, the comparative study of the main characters of them is completed with an analysis of character as a person and as a role that is applied to the protagonists of the films of Almodóvar: Pablo Quintero and Antonio Benitez, Law of Desire; Becky del Paramo and Rebeca Giner, High Heels; and Leo Macias, The Flower of My Secret. For this purpose, we applied the template of analysis of characters created in 2009 by the research group on Analysis of Means, Images and Audiovisual Stories (ADMIRA) at the Audiovisual Communication and Publicity Department of the University of Seville, based on Francesco Caseti and Federico di Chio’s approaches. This qualitative tool –being the heir of the work of other relevant authors in the narrative such as Algirdas Julien Greimas and Vladimir Propp allows us to know key elements of the fictional beings such as the physical aspect, the way they talk, their character, their way of relating to others, their thoughts, their feelings, their personal development, their social, economic and cultural level, their sexuality, or the type of actions they take and their role in history. Undoubtedly, “the narrated plots are always the plots of someone ‘, events and actions related to whom, as we have seen, has a name, an importance, an incidence and enjoys particular attention: in a word, a “character” (Casetti and Di Chio, 2007, p. 159).

By analyzing these fictional beings, it is intended to highlight the elements that approximate the characters of Williams, their consistent construction as being taken from real life that plausibly work and evolve in the film, and the circumstances that determine and humanize them due to their universal character despite their tragedy. Melodrama being the most popular genre for its emotional and sentimental nature, this analysis attempts to facilitate understanding of the characters and the process of identification with the viewer because, although the argument must be solid for the story to work, the fictional beings have must be well defined as they are the ones who support the action. For these issues, the analysis as a person and role arises as a resource to try to learn more about the psychology of the characters of Williams and Almodóvar, since in both cases fictional the fictional beings tend to stand out of the action.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. The classic American melodrama and the adaptations of Tennessee Williams

Melodrama is the genre that has greater experience in film history for being present in the first silent films and also in much of the experiences of the characters in films of other styles. This intergeneric character indicates the existence of films inserted into the melodrama by clear thematic issues, while “many others who would belong to other genres – even those who seem opposites such as comedy – contain numerous ingredients within the scope of the melodramatic, which brings out the excessive sentimental stories away from it “(Pérez Rubio, 2004, p. 30-31). With a patent popular character, it has its origins in the theater of the late eighteenth century and was very successful in 19th-century romance and melodrama. The emotional charge of the story together with the drama of fictional beings had music to reinforce the tragic tone of its representation: The etymological definitions refer to the presence of music at the origin of the term, and historical to the genesis of the “form”, then the importance of music in the course of representation is noted for its character of “stressed”, of “contrast”, of “relief”, of climax, etc. (Monterde, 1994a, p. 54) The musical factor played a key role in the adaptation of this genre in cinema in its silent beginnings, since the only way to express the dramatic tension and emotions of the characters was through music that was played in the hall during the screening, as it was done in the scene. Thus, key elements of the genre as the division of fictional beings into good and bad, the presence of chance in romantic action, plot twists brought about by crime or death, moralizing end, or appeal to public sentiment, were transferred to the new filmic melodrama underlined at the musical level. Music has played a crucial role in its development “for its ability to intimately connect with the audience, identify the audiovisual message, synthesize the exposed primary emotions, identify the audience with the characters and finally homogenize the set of the film” (Zurián & Vazquez, 2005, p. 373). With these assumptions, the film melodrama is about the emotional nature of the situations to facilitate more direct identification between the viewer and the characters, and therefore, has a classic and popular character (Balmori, 2009).

Although it is present in the most diverse films, it is in the Hollywood industry where this genre has had a broader development and has exerted more influence globally. During the period from the arrival of talkies in 1927 to the fall of the censorship system in 1967, melodrama had extensive development. Gradually, Manichaeism of a theatrical type initially installed to lead to more complex situations that could not be solved with a solution that only distinguished right from wrong was abandoned. Although originally the moral question was decisive, as seen in the happy ending of initial melodramas, the destabilization of the Hays Code allowed the entry of taboo subjects that had great potential. In the late forties, romanticism inherent in the films of this genre gave way to passionate character issues with not necessarily positive outcomes for the suffering characters. Films that announced this trend such as Jezebel (William Wyler, 1938), Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939), Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz, 1945), Leave Her to Heaven (John M. Stahl, 1945), or The Heiress (William Wyler, 1949). Thus, “the genre experienced a major shift toward cruder, more direct and passionate arguments from the fifties, just as Williams’s works were adapted to the cinema” (Duran Manso, 2015a: 684). Film adaptations of the southern playwright had a prominent place in the melodrama made in Hollywood after World War II and contributed to the gradual dissolution of the code, although they underwent the ravages of censorship due to their sexual charge. This happened in A Streetcar Named Desire, Baby Doll or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, although the ability of Elia Kazan in the first two cases and Richard Brooks in the third made it possible that some of the raised issues could be perceived, such as nymphomania and adultery, the desire for a child, or homosexuality, respectively. These themes enabled passion, and not just the loving nature, starred melodrama in the fifties and, furthermore, the public -not used to seeing these situations on the screen, connected with the characters. In a time when Hollywood was heading to thematic freedom with fictional plots and beings closer to real life, this genre experienced a remarkable development although it maintained much of its original proposals. In addition to these films, Williams’s The Glass Menagerie, The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), Suddenly ... Last Summer, The Fugitive Kind (Sidney Lumet, 1960), Summer and Smoke (Peter Glenville, 1961), the Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, Sweet Bird of Youth, The Night of The Iguana, This Property Is Condemned (Sydney Pollack, 1966) and The Cursed Woman (Boom !, Joseph Losey, 1968), among which “ some of the most relevant melodramas made in Hollywood in the decades of the fifties and sixties stand out” (Duran Manso, 2015a: 683). Due to the success obtained, over the years, works of great success on Broadway by contemporary playwrights to Williams such as William Inge, such as Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955) and Splendor in the Grass (Elia Kazan , 1961) were adapted too. Melodrama had a special role in these years, even those set in war-torn areas like Love is a Many-Splendored Thing (Henry King, 1955), or exotic like Mogambo (John Ford, 1953), but those that had greater development were the family type dealing with sentimental, sexual and generational issues in southern or provincial environments, such as those of Williams. Thus, the plot tension of a melodramatic nature increased enclosed spaces where family pressure or puritanical society constrained the lives of the characters. This scheme was also present at prominent melodramas as Giant (George Stevens, 1956), Written on the Wind (Douglas Sirk, 1956) and Peyton Place (Mark Robson, 1957), or Imitation of Life (Douglas Sirk, 1959) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (Stanley Kramer, 1967), where the racial aspect played a decisive role. Although the code forbade interracial relationships, these films managed to weaken it in addressing an issue that had not been deal with until Pinky (Elia Kazan, 1949). These titles and especially those of Williams contributed to the evolution of melodrama and subsequently influenced filmmakers close to the classical American cinema like Pedro Almodóvar.

4.2. The characters in Tennessee Williams: types and prototypes

The universe of Tennessee Williams is characterized by the decline of the southern class due to his birth and education in the state of Mississippi and the artistic and vital refuge he found in New Orleans, his city of reference. Therefore, this playwright has a clear tendency to address issues such as the current situation of the so called Old South scenario -in which most of its texts took place-, fear of characters who do not recognize themselves, and sex as liberating way to escape a stifling and closed society (Duran Manso, 2011). The construction of fictional beings of great dramatic complexity, but at the same time very close to individuals from everyday reality, shows the ability of this writer to delve into the depths of the human soul and, ultimately, his own. In addition, the parallels between his life and his work is reflected in the characters, since some act as his alter ego, some evoke his mother or his sister, and others are inspired by acquaintances (Williams, 2008). The beings created by Williams can be divided into the following five groups:

–Ladies to the limit. Williams created Southern women inspired by her mother, Edwina Dakin Williams, and presents them as the inheritors of the plantations of the Old Southern families. After the Civil War and the loss of Southern values, they cling to their past and cultivated mind but are lost in a new society that does not understand them and which they do not want to understand either. It is women who range from youth to maturity, of great charisma and beauty, but of an extremely vulnerable nature. The clearest examples are Amanda Wingfield and Blanche DuBois, the protagonists of The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire, respectively.

–Tormented youth. Like the above, they are determined by the conflict between individual and society, but less sharply. They often take refuge in their particular universe due to personal problems, family conflicts or sentimental disappointments or suffering, and this prevents them from being happy. In addition, they live in puritanical societies that continually question their desire for independence and freedom. Although they embody universal values that are common to all young, they have a tragic existence. The best examples are Brick Pollitt and Chance Wayne, the protagonists of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Sweet Bird of Youth, respectively. –Integrated in life. These characters survive with the acceptance of their present, which is not always what they like or prefer, and this allows them to find the way to be happy. They have their feet on the ground and are aware that they have to fight to get ahead, and as they have not lost anything because they lack a glorious past, they have a more positive stance than ladies to the limit. Williams presents oppositely fragile and nostalgic dreamers that focus almost all his work to contact the social reality. The protagonist of A Streetcar Named Desire, Stanley Kowalski, and the star of Suddenly ... The Summer, Catharine Holly, belong to this group.

–Key Parents. They represent the counterpoint of tormented youth that often embody their children and sometimes the prison in which they find themselves. They are ruthless, authoritarian, repressive and unable to empathize with those who think like them or have a sensitive nature. They have long struggled to achieve the high status they have and are concerned about providing a comfortable life for their family, but have forgotten to give them love. Therefore, the generational conflict they have with their descendants is very pronounced. The patriarchs of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Big Daddy, and Sweet Bird of Youth, Boss Finley, are the most relevant cases.

–Fugitives and souls adrift. They are aimlessly in life because of the difficult personal or professional situation they face. Fear of failure, loneliness or insecurity have them dominated, and they are even on the verge of depression because they find no meaning in their lives. They usually escape through alcohol, drugs or sex, but these formulas do not represent a solution to the spiral that is drowning them. They usually live alone, get along with their meager family, their emotional state is unstable, and have an interesting social life. This is the largest group and the clearest example is Karen Stone, the star of The First Roman of Mrs. Stone.

Despite its psychological complexity, two prototypes can be taken from this classification, a male and a female. The first group is notable for their almost nonexistent relationship with their fathers and their narrow but destructive relationship with their mothers; a strong desire for independence collides with a certain limitation to escape their reality; and a developed sexuality. Meanwhile, the second group is characterized by a strong family commitment that haunts when her world loses its structure; a difficult adaptation to the society in which they are; and sexual desire that allows them to escape reality. Thus, the family, the clash between the inside and the outside worlds, and sex are the axes that articulate the characters of Williams and precisely, are also present in the protagonists of the melodramas of Almodóvar. For this reason, this type is applicable to the characters created by Almodóvar that are analyzed.

4.3. Williams melodrama in the universe of Pedro Almodóvar

The films framed in classic Hollywood melodrama had a strong presence in other film industries due to the use of universal emotional formulas and the US hegemony as a filmic engine. Thus, they had predominance over Pedro Almodóvar, who grew up watching titles like Johnny Guitar (Nicholas Ray, 1954), Picnic, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof or Splendor in the Grass while studying at a religious school in Caceres, which posed a contradiction with the teachings he received. The adaptations of Tennessee Williams played an important role in its cultural and educational development, determined his cinephile origin, and let him know the keys of the genre. Therefore, the filmmaker confessed to Strauss (2001): “What I did not know was that, decades later, some of the images projected on the screens of my childhood would have my signature and be marked by those first films where T. Williams was my true spiritual director” (p. 134). Thus, the films of the Southern writer marked the director’s style, but other masters of melodrama such as John M. Stahl or Douglas Sirk also influenced him. The connection between Williams and Almodóvar is apparent in narrative, spatial, thematic elements regarding character creation. First, both located most of their stories in the same city that is in keeping with their character. While the New Orleans fifties represents the decline of the southern elite class to which Williams belonged, the capital of Spain in the eighties is to Almodóvar a place of seething. Thus, the director explains that “like my characters, Madrid is a wasted space to which it is not enough to have a past because the future keeps exciting it” (Strauss, 2001, p. 70). These spaces are actively involved in his films to host the controversial issues addressed, such as adultery, homosexuality, or nymphomania, since both tend to touch aspects of daily life that had been hidden by a moral issue and, ultimately, places them in what is transgressive. For this reason, the family relationships they create are far from those recreated by their melodramatic predecessors as conflicts have a strong psychological burden; although, to the former, they verge upon oppressiveness and, to the latter, the tragicomic. Third, Williams and Almodóvar share a tendency to build strong characters who are far from the standards established by a conservative society. If, in the universe created by Williams, fugitives were outside the family and social dictates, the universe created by Almodóvar thrives on drug addicts, prostitutes and homosexuals who, after being marginalized for decades in the Spanish cinema, began to have visibility. Both also agree in the prominence they give to women in their films, either housewives or entrepreneurs or artists, and this draws them close to the classic melodramas of George Cukor or Sirk. Moreover, the playwright and the filmmaker agree on the importance of music as a melodramatic factor. Each has a style present in his films reflecting the characterization, status and personal development of their fictional characters: the sensuality of jazz in the case of the southern author and sentimental chanson, bolero and ranchera in the case of the director from La Mancha. Thus, in the films we studied, Ne me quitte pas, by Jacques Brel, indicates the deep love that Paul feels for John, and I doubt, played by Los Panchos, that of Antonio for Paul in Law of Desire; Think of me, in the voice of Luz Casal, he reveals the feelings between Becky and Rebecca in High Heels; And in The Last Drink, sung by Chavela Vargas, Leo’s despair is expressed after the abandonment of Paco in The Flower of My Secret. Therefore, Almodóvar follows: “songs are an active part, a kind of dialogue in the scripts of my films and say much about the characters. They are not just for show “(Strauss, 2001, p. 69). These styles are closely linked to melodrama because their lyrics speak of love, passion, separation, pain, or heartbreak; constant gender issues. As says Holguin (2006), “music adds to the dramatic situation of the characters, penetrating their psychology, giving emotions and feelings to characters that move by hatred, love and revenge” (p. 222). Thus, we can say that there is parallelism in the melodramatic construction of Williams and Almodóvar, although the latter takes the genre to his ground by introducing features from fields as diverse as comedy, suspense, the Spanish popular culture or subversive the New American Cinema. Being an heir of classic melodrama, he reformulates one of the most established genres and transgressors elements compose a collage full of intertextual quotations that makes his universe very unique and easily recognizable. Thus, he creates “a melodrama of his own that is played by characters who inhabit a fictional universe where the force of passion predominates, but in which there is no classical Manichean division of the characters of traditional melodrama” (Rodríguez, 2004, p. 156). The many references to movies, actors or characters of classic Hollywood that appear in his films, but also European filmmakers ranging from Ingmar Bergman to Roberto Rossellini, are one of his hallmarks.

In this sense, direct or indirect quotations refer to titles by Williams like The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, as occurs in Back (2006), or Pepi, Lucy, Boom And Other Girls Like Mom (1980), respectively. However, also they refer to other melodramas as Duel in the Sun (King Vidor, 1946), Matador (1985); Johnny Guitar, in Women on the Edge of a Nervous Breakdown (1989); or All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950) in All about My Mother (Perales, 2008). In addition, these quotes are usually known by the viewer and facilitate understanding of the character, because what happens on screen is similar to what happens in the film they evoke. Thus, “the appointment of the Hollywood text is always an organic part of the film to be perfectly integrated into the plot, its main function establishing thematic, narrative and plot clear parallels between the text of Almodóvar and the original text” (Rodriguez, 2004 p. 145). Almodóvar’s film where a greater number of references is given to a text of Williams is All About My Mother, but, although the story has a direct analogy with A Streetcar Named Desire, his characters have such a clear link, except for Manuela Cecilia, played by Roth, who seems an evolution of Stella DuBois.

4.4. Analysis of characters in melodramas of Pedro Almodóvar

Love between a couple led to the tragedy, the complex relationship between a mother and a daughter, and loneliness in a mature woman are typical themes of melodrama. In addition to focusing various texts of Tennessee Williams, they articulate in this order the arguments of Law of Desire, High Heels and The Flower of My Secret. Thus a parallel between the characters of the playwright and Almodóvar is established.

4.4.1. The melodrama of passion: Law of Desire

The sixth film directed by Almodóvar is the first produced under the label with which he made his other films: Desire. In Law of Desire, passion of three gay guys – directly and without falling into stereotypes –, the excesses of fame, transsexuality, family abandonment, or abuse of the clergy come together for the first time in the Spanish cinema. Although filmmakers like Pier Paolo Pasolini, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, or Stephen Frears had already addressed homosexuality, “Almodóvar was the only one who has approached it so bravely and sincerely, presenting it as a natural fact, avoiding all kinds of sublimation” (Holguín, 2006, p. 248). The characters that are analyzed are Pablo Quintero and Antonio Benitez, played by Eusebio Poncela and Antonio Banderas, respectively, for although Tina Quintero, played by Carmen Maura, shares the spotlight with them, her transsexual condition takes her away from the beings created by Williams. Both the addressed topics and the characters that develop them, and the use of music with a clear dramatic purpose, lead to his first major melodrama and also “the first great film of Almodóvar” (Sotinel, 2010, p. 33).

4.4.1.1. Pablo Quintero

Like Tennessee Williams who had his alter ego in the protagonist of The Glass Menagerie -the young poet Tom Wingfield-, it can be assumed that this character is the alter ego of Pedro Almodóvar, to “make the portrait of a filmmaker who no longer controls anything that is overtaken by real or fictitious events” (Strauss, 2001, p. 63). Following the typology of characters created by Williams, Pablo belongs to the group of fugitive souls adrift and that is carried away by the occurrences without being able to take control of their life. Despite having talent as a filmmaker, youth, fame and public recognition, he goes through a difficult personal situation that influences his career. The protagonist lacks a stable partner, he is not reciprocated in love the way he needs, and is increasingly self-enclosed, and this explains his refuge in alcohol and especially on cocaine. Although he lives alone, he has a very close relationship with his sister Tina and with the daughter of her mistress, Ada, who are his only family. However, they can not give the emotional tranquility he needs, as only he holds the key to confront himself and understand his own feelings. By analyzing him as a person, we can extract that Pablo is from 30 to 35, he is tall, thin, blond and blue-eyed, and this combination makes him attractive. In addition, he is dressed in the fashion of the eighties, wearing costumes with big shoulder pads, tight jeans, and printed shirts. As for his speech, he has a rich discourse in words but he is not very talkative and often uses a slow and direct tone of voice that only rises when he perceives that his privacy is invaded. However, during the plot, his speech is stable and does not undergo a major transformation to an iconographic level. From a psychological point of view, he is good-natured but is introverted and unstable, although it seems that he perfectly controls his life. At first, he can be distant in dealing with others, even with his partners, but he has a very close relationship with his immediate environment and, in fact, Ada takes on a parental role. As for his thinking, he is quite sensible, as evidenced in his employment decisions, but he is dominated by a feeling where love and desire are the protagonists. He is in love with Juan, who is starred by Micky Molina, but is frustrated because Juan does not correspond with the intensity he needs. When he goes to Conil to work in summer, Antonio suddenly comes into his life and they start a relationship which he wants to but cannot stop. In this regard, Almodóvar follows: “Eusebio’s character has a very strong need to feel desired but, as he tells Antonio, not by any” (Strauss, 2001, p. 68). Herein lies the real problem of Pablo. His love for Juan, whom he has idealized, is different from what he feels for Antonio, a young man who captivates but also overwhelms him.

The protagonist experiences a remarkable evolution after the car accident following the death of Juan. As the impact leaves him amnesiac, it becomes more melodramatic as the disease or disability “always magnifies the image of weakness of the character and compassion comes with it” (Monterde, 1994a, p. 58). After overcoming his illness, he understands that he has really fallen in love in such an extreme way as Antonio desired. Pablo has a high socioeconomic and cultural level because of his career but he never appears in opulent surroundings. As for his sexuality, he embodies the liberated homosexual who accepts himself and coexists perfectly with his orientation. Thus, it can be said that the purpose of the filmmaker is “validate and” normalize “sexual otherness as the very essence of heterosexuality, with love above the carnal desire that truly unites individuals in male homosexual relations” (Zurián & Vázquez, 2005, p. 446). Therefore, the being created by Williams who is directly referred to is Sebastian Venable -the poet protagonist of Suddenly ... The Last Summer- because, like the latter, he has youth, beauty, prestige, and assumes his homosexuality, and enjoys it, being and artist and living in an elitist environment. Also, he also it evokes the own Williams for the same reasons. Because of this, the main role he plays is that of a fugitive, but he assumes the role of a hero at the end when he accepts his reality.

4.4.1.2. Antonio Benitez

This character can be considered an evolution of the protagonist of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Brick Pollitt, who shares a family environment of high and traditional status, the hidden way in which he lives his true sexual orientation, and his desire and obsessive love for another man. Within the classification of characters of Williams, Antonio belongs to the group of tormented youth because he lives a double life as he is unable to accept his homosexuality; he belongs to a family of the high society of Jerez de la Frontera (Cádiz) that, consequently, is Catholic, very conservative, and would never accept his condition; he is trapped under the rule of his overprotective mother, an elegant lady of German origin played by Helga Liné; and ultimately, his desire for freedom constrained by a suffocating environment. This usual dichotomy between the desire of youth and family stiffness is worsened when he progressively and obsessively takes shelter in the relationship that he begins with Pablo. Love, passion and the desire he feels for him, but also jealousy, lead him even to commit murder and suicide.

Following the analysis as a person, physically Antonio is 20 year old, tall, slim, dark, dark-eyed, and with gel-combed hair parted on the side, and this looks as close to the prototype of a gallant. His classic image is linked to a system based on poles of basic colors of Lacoste, shirts, slacks and Castilian shoes. His speech is characterized by being persuasive, despite his youth, and the firm tone of voice becomes very aggressive if things do not go as he expected. While maintaining his its style, he undergoes an iconographic transformation when he buys the same emblazoned shirt as Pablo, a garment that “will allow Antonio believe that he possesses Pablo, the subject and object of his desire” (Suarez, 2012, p. 124), and especially when wearing jeans, boots, said shirt, a leather jacket and his hair without hair gel to kill Juan. Psychologically, he is decisive, and as the film director, he is good-natured but unstable. In dealing with others he is polite and pleasant, but he is a victim of the close relationship with his mother, who, like Violet Venable in Suddenly Last Summer ..., does not want to see that his son is gay. In this sense, the same pattern of characters in this title by Williams with an absent father is because he is a member of the Andalusian Parliament, an arrogant, elitist and possessive mother and a gay son who needs to break the umbilical cord and live his life. Because of this oppressive environment, he asks Pablo that, when writing letters to him, do it with a girl’s name – Laura Q –, to avoid suspicion; an idea that “demonstrates the sedimentation of regulatory and punitive bias in the new young Spanish generation and conflicts that still exist in gay self-awareness,” (Zurián & Vázquez, 2005, p. 447). However, in his relationship with him, he is natural, affectionate and committed. Although it has good background, his thinking is calculating and devises a plan to kill Juan, so he is dominated by his feelings. Pablo represents the free man who accepts and lives in coherence with himself, and Antonio falls in love with him to such an extent that he develops a pathological obsession. Therefore, Almodóvar indicates that “to Antonio, desire is something immediate which is transformed into motor energy” (Strauss, 2001, p. 68). This passion is so destructive that the only way out is suicide, as happens to other gay beings created by Williams such as Allan Grey – the husband of Blanche DuBois – in A Streetcar Named Desire – or Skipper in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. This character undergoes an interesting development because of a repressive field and, ultimately, indirectly acknowledges his homosexuality in public, yes, without the presence of his mother and before shooting himself. Antonio comes from a higher social class and moves in cultural areas of Madrid, where he lives because he studies at the University. At a sexual level, he represents the repressed homosexual for family reasons who wants to break his barriers, and when he falls in love he decides to break free. He also plays the role of antihero, although, given his complexity, he quickly passes from being a lover to being a psycho.

4.4.2. The generational melodrama: High Heels

The ninth film of Pedro Almodóvar is the most faithful to the classic Hollywood melodrama. The tone of the story, the relationship between the characters and their stylized aesthetics, both costumes and sets and music, make High Heels an heir of Williams and Douglas Sirk. The film has one of the most powerful melodramatic situations: separation and reunion of fictional beings, in this case, a famous mother and an abandoned daughter. On this point, Monterde (1994a) asserts that “the idea of separation implies narrative importance of the trip -in a triple sense of displacement, psychological development or social mobility-, and of course it has its corollary in the reencounter, either because they finally make it or because it is definitively impossible “(p. 57). The studied characters are Becky del Paramo and Rebeca Giner, played by Marisa Paredes and Victoria Abril, respectively -despite the fact that judge Dominguez and the transvestite Femme Letal, who is played by Miguel Bosé, act as intermediaries between them-, since they evoke other mothers and daughters of the southern author. As Almodóvar points out: “the family is always a dramatic material of the first order” (Strauss, 2001, p. 67).

4.4.2.1. Becky del Páramo

This character has a certain parallelism with the characters created by Williams Amanda Wingfield, Blanche DuBois and Violet Venable, with whom it shares a great physical attraction, an overwhelming personality, a remarkable charisma, and more shadows than light. Depending on the type of characters of Williams, Becky is part of the ladies at the limit but has traits of dominant parents in regard to the relationship with her daughter. In this sense, she coincides with the former in living engrossed in her world of splendor, if any, her career as a singer of boleros makes it difficult for her to face the present in which she is now, as happens when she returns to Madrid after fifteen years; and displays a fragility to problems. On the other hand, from the latter group she retains her firm position against the authoritarian Rebeca; the inability to put herself in her place after having abandoned her; and the firm belief that all her sacrifice was so that her daughter did not lack anything, when she really did it for her personal triumph. In this way, she shows melodramatic traits proper to Williams’s characters. By analyzing her as a person, we can extract that Becky is around 50, tall, thin, blonde, has a sexy look and smile, and knows how to exploit her beauty. Elegance is the value that best defines her, and it is shown by her sophisticated wardrobe made up of suits, gowns, high heels, and other accessories that denote that “she embodies head to toe the image of a star diva “(Zurián & Vázquez, 2005, p. 168). As for her speech, she has a great way with words and a persuasive speech, but her pleasant tone becomes dominant when she feels attacked, ie, every time her daughter reproached her absence. Her main iconographic transformation occurs when, at the end, she abandons her usual costume for a gown because of her heart disease. From a psychological point of view, she has a frivolous nature because of her level as an international singer, but behind the facade of professional success, she is an unstable character. In personal relationships, she stands out for her charisma but, because of her fame, she is often distant with others, as demonstrated when she meets Femme Letal and judge Dominguez. With Rebecca she has a bond of love / hate because she is aware that she has not been good and, though she even tries to be loving and caring, she does not hesitate to use her weapons to stand over her, as if instead of her daughter were a rival with which she had to compete. In addition, their reunion after fifteen years shows their scarce naturalness to act as a mother as she maintains a posture of star; the role she plays best.

Her vital objective has been the world of singing and so she decided to go to Mexico when her daughter was little. This resignation reveals her great spirit of sacrifice but also her selfish thought because the girl wanted to go with her. Also, her feelings are characterized by marked egocentrism, but, basically, she is emotional and sentimental as “in melodrama, there is no love like the love of a mother (and to a lesser extent a father), no matter how destructive it can come to be” (Monterde, 1994b, p. 69). When she best expresses her feelings as a mother is when, during her first concert in Madrid, she dedicates the bolero Think of Me to Rebecca after saying she is in jail. However, in moments of maximum tension, the melodrama in her songs is confused with her life. Becky experiences a significant evolution going from a dominant position to a redemptive one: first, suffering a heart attack on stage; then she pleads guilty to the murder committed by her daughter; and third, when dying. Thus, “feeling that her end was near, Becky decides to incriminate herself in favor of her daughter, a final test of love to redeem her selfishness and narcissism” (Méjean, 2007, p. 67). She has a high socioeconomic and cultural level by profession but her origins are humble, because she grew up in a superintendent’s apartment in Old Madrid. She is a heterosexual character that appears in the plot sentimentally attached to her ex-husband; her previous partner before her Mexican stage, Alberto; and Rebecca’s husband, Manuel. Becky plays the role of a star and, especially, a denatured mother (Sotinel, 2010).

4.4.2.2. Rebeca Giner

This character is one of the most melodramatic of Almodóvar along with Becky del Páramo. Although she evokes Laura Wingfield due to the domination of her mother over her, as she is not sick she directly reminds us of Catharine Holly, who suffered the hard pressure of her aunt Violet Venable in Suddenly ... Last Summer but she could confront her and tell, with no fear, all the truth about her cousin Sebastian. According to the typology of fictional beings of the southern playwright, Rebecca belongs to the group integrated in life because, despite her being abandoned by her mother, she does not live tormented by it. Contrary to expectations, she bears the pain of separation, resignedly accepts reality and has found peace through her job as a television presenter and her marriage to Manuel, a former lover of Becky. She is intelligent, feisty, simple, has capacity for forgiveness and shows an enormous strength despite her youth. Following the analysis as a person, Rebecca is about 30 years, average height and is a good guy, has a boyish face, and her light brown hair is cut short. This youthful image is completed with a costume consisting of Chanel jacket suits, accessories of the same firm, and evening dresses. Her speech is based on a talkative but slow speech and a direct voice tone, and though she is not very talkative she always does it decisively. However, her words become hurtful and she considerably raises her voice when she has an argument with her mother. The main iconographic transformation occurs when she goes to jail and her fine clothing is replaced with a pair of jeans and a sweater with a wide diamond pattern of colors that do not suit her and emphasize her fragility. Psychologically, Rebecca has a resigned nature due to the difficult relationship with Becky, and cries a lot with everything about it, from the songs, memories, or disputes. Regarding her personal relations, she is affable due to the emotional deprivation she undergoes because of her mother. With her, she tries to be accommodating when her mother returns to Spain but the torment of her abandonment prevents their relationship from being fluid. So, this link is marked by a mixture of love and hate, forgiveness and pain, but ultimately self-denial, for her love as a child exceeds her rancor. While with Manuel she shows a failed marriage relationship, with Lethal she feels loved by herself.

She has sincere thinking that is extensible to her feelings, where unconditional love for her mother gives meaning to her existence. Therefore, when she was little, she did not hesitate to kill Alberto, a former boyfriend of Becky, for opposing her musical career, and, more, Manuel, for being an obstacle to their being together. In this sense, Rodriguez (2004) says that, together with “Antonio in Law of Desire, she is a one-dimensional melodramatic character, absolutely dominated by the erotic-amorous passion she feels for her mother, for whom twice she resorted to murder” ( p. 178). She also has a sense of guilt because she never understood how Becky left her with her father for years and did not take her to live in Mexico, and an inferiority complex. This explains why, to feel her closer, she married one of her former lovers and found refuge in Letal’s performances, a transvestite who imitates and who she falls in love with. She undergoes an evolution after facing her mother in court and expresses the pain she has suffered since childhood, and how it makes her feel inferior, citing as an example the mother-infant relationship in Höstsonaten (Ingmar Bergman, 1978). This meeting serves as a catharsis to get out all the harm she had, and helped her to forgive Becky and take care of her until she died in her arms. The socioeconomic and cultural level of Rebeca is high, as indicated by her housing, clothing, education and profession. She Is a heterosexual character who finally manages to be happy with Letal and the son they both wait for. She occupies the role of a good girl because “she always saw herself as a nuisance, and just wanted the love of her mother” (Zurián & Vázquez, 2005, p. 430).

4.4.3. The melodrama of maturity: The Flower of My Secret

The eleventh film of Pedro Almodóvar speaks of heartbreak, loneliness, and the encounter with oneself; topics that are closely linked to melodrama. However, this gender is “more contained than in previous works, because now, instead of focusing on the excesses of passion, the director focuses his gaze on the pain of the protagonist because of the loss of her beloved” (Rodriguez , 2004, p. 180-181). The Flower of My Secret evokes the only novel of Williams that became a movie, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, and it has direct connections to classics like Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943), The Apartment (Billy Dating Wilder, 1960) or Rich & Famous (George Cukor, 1981); which shows the cinephile nature of the filmmaker. The only character that is analyzed is Leo Macías, played by Marisa Paredes, even though Angel, played by Juan Echanove, becomes her savior and reminds us of the character created by Williams Dr. Cukrowicz of Suddenly...Last Summer. As Almodóvar suggests, “everything rests on her, the others only appear depending on her route, which avoids dispersion. Leo unites them all “(Strauss, 2001, p. 138).

4.4.3.1. Leo Macías

This character reminds us of Karen Stone, the star of The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, because she is no longer young, is going through a bad professional time, and love has escaped. For these reasons, following the classification of characters of Williams, Leo belongs to the group of fugitive souls adrift, since she is going through a crisis of inspiration in her literary career; she suffers the repeated absence of her husband, Paco, played by Inmanol Arias, who works in Brussels; and she is depressed. In addition, she takes refuge only in waiting the calls from Paco, making her an emotional dependent, and alcohol. The protagonist lives alone in the center of Madrid, she has a good relationship with her mother and sister, who live in Parla (Madrid) and are her only family, and has little social life, but enjoys the anonymity brought about by her pseudonym Amanda Gris. However, she is in a dangerous emotional drift that leads her to float in a vacuum. By analyzing her as a person, we can extract that Leo is about 50 years old, is tall and slender, has brown to coppery hair, a wide smile and a sad look, but is appealing. Her wardrobe reflected her mood well when wearing casual clothes and sober tones when she feels bad, and, on the other hand, stylized and colorful business suits or dresses when she feels well. Her style indicates a “firm representative of the bourgeois world, she wears sober and minimalist clothes, without fanfare” (Holguín, 2006, p. 284). Leo is direct in her speech and uses a paused tone of voice that she often alters because of her depression. The most important iconographic transformation that she undergoes occurs when she leaves the village with her mother and there she appears wearing old but comfortable clothes, a casual bun, and sneakers. From a psychological point of view, she has a vulnerable nature, because, like Karen Stone, she maintains her beauty and charm but suffers a creative and sentimental crisis. This explains that the romance novels she should write for Fascination Publishing House turn out to be black and she sees that her life is over. In this regard, Almodóvar says that “Leo is a woman alone and loneliness has made her a tremendously fragile being. It is not a recent fragility, but caused by years and years of solitude “(Strauss, 2001, p. 133). In her personal relationships, she is accessible to people in her immediate environment and is distant with others. With whom she has a closer connection is her family, her friend and confidante Bety, and her assistant Blanca, while with her husband she has a very complicated relationship. However, Angel becomes her main support when she finds no way out.

Because of her personal situation, she have insecure thinking and a way to feel visceral. Her emotional state is represented well when she is in a barroom and Chavela Vargas appears on television singing In The Last Drink, “Vargas, maternal or fraternal figure, seems to be singing directly to Leo, urging her to a shared agreement to stop drinking and destructive love that should no longer have the power to hurt the two of them” (Zurián & Vázquez, 2005, p. 172). The writer undergoes a significant evolution after attempting suicide following her breaking up with Paco, for “she gets out of her lethargy thanks to the voice of her mother, whose voice she hears in the distance on the answering machine, as if the one that bore her could save her from death “(Méjean, 2007, p. 103). Her origin is more important than one may think and, therefore, she takes refuge in her family and take a trip with her mother to the town where she was born that serves to put her life in order. Leo has a high socioeconomic and cultural level due to the literary world. In addition, she is heterosexual, and although she suffers for her husband she finally decides to give Angel a chance. The writer plays the role of a desperate woman for her difficulty to find a way out.

5. CONCLUSIONS-RESULTS

Pedro Almodóvar’s tendency to draw inspiration from the classic American cinema makes his melodramas have a similarity with the themes and characters from the reference Hollywood films. The director is an admirer of the masters of the genre, such as John M. Stahl or Douglas Sirk, and his transgressive nature is very close to Tennessee Williams. Thus, in the universes of Williams and Almodóvar there is certain parallelism indicating the presence of the former in the latter at a melodramatic level. Both share sexually charged plots, psychologically rich characters – with women specially standing out –, and spaces with an important role at a narrative level. In addition, in adapting this gender to his aesthetic vision –providing it with “a comic-dramatic sense with surreal touches” (Holguín, 2006, p. 73) -, the analyzed films have elements of his personality and remain faithful to the essence of melodrama. In this regard, Law of Desire, High Heels, and The Flower of My Secret deal with issues specific to this genre that, being starred by homosexuals, a daughter annulled by her mother or a mature woman over the edge, respectively, make reference to titles of Williams that have influenced Almodóvar, such as A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on A Hot Tin Roof, or Suddenly ... Last Summer

The analysis of the types of characters of the southern playwright in five groups has allowed us to classify them through aspects of their construction and characterization, and also to compare them with the protagonists of the melodramas of Almodóvar due to features of a psychological sort they contain. For its part, the study allows us to better understand how the fictional beings are and act based on their appearance, age, speech, character, interests, circumstances, concerns and aspirations, and also their sociocultural and sexual dimension, or the role they have, among other things. This double analysis shows that the characters of Almodóvar and Williams are designed to participate in the story in a natural, relevant and credible way, and they are very close to real-life beings; which affects their melodramatic potential.

The research work we developed a llows us to demonstrate that each of the types of characters of Williams are present in the fictional beings of the melodramas of Almodóvar that we studied: Pablo, Antonio, Becky, Rebeca and Leo. Despite their being from 20 to 50 years old, they stand out for their physical attractiveness, an unstable character even with different personalities, their dependence on love and desire, their suffering emotional conflicts, their being both heterosexual and homosexual, and their belonging to a higher social class. Also, the roles are closely related to the nature of the type in which they fall into. These features present in the characters created by Williams match the reality of the ones we analyzed. Which leads us to consider that the fiction beings of the most classical melodramas of Almodóvar are closely related to those of Williams.

REFERENCES

1. Almodóvar A (productor), Almodóvar P (director) (1986). La ley del deseo [cinta cinematográfica]. España: El Deseo S.A.

2. Almodóvar A (productor), Almodóvar P (director) (1991). Tacones lejanos [cinta cinematográfica]. España: El Deseo S.A. / CIBY 2000.

3. Almodóvar A (productor), Almodóvar P (director) (1995). La flor de mi secreto [cinta cinematográfica]. España: El Deseo S.A. / CIBY 2000.

4. Balmori G (2009). El melodrama. Madrid: Notorious ediciones.

5. Casetti F, Di-Chio F (2007). Cómo analizar un film. Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós.

6. De-Rochemont L, Wolff L (productores), Quintero J (director) (1961). La primavera romana de la señora Stone [cinta cinematográfica]. Reino Unido: Warner Bros.

7. Diez E (2006). Narrativa fílmica. Escribir la pantalla, pensar la imagen. Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos.

8. Durán-Manso V (2011). La complejidad psicológica de los personajes de Tennessee Williams. FRAME, 7, 38-76. Recuperado de http://fama2.us.es/fco/frame/frame7/estudios/1.3.pdf.

9. Durán-Manso V (2015a). El dramatismo de los personajes de Tennessee Williams en el melodrama de Pedro Almodóvar: Tacones lejanos. En: E Camero, M Marcos (coords.) Hibridaciones, transformaciones y nuevos espacios narrativos (Tomo I; pp. 678-691). III Congreso Internacional Historia, Literatura y Arte en el Cine en español y portugués. Centro de Estudios Brasileños. Universidad de Salamanca.

10. Durán-Manso V (2015b). El horror psicológico en Tennessee Williams: el tormento de sus personajes en el cine. Cauce. Revista Internacional de Filología, Comunicación y sus Didácticas, nº 38:71-88.

11. Feldman CK, Wald J (productores), Rapper I (director) (1950). El zoo de cristal [cinta cinematográfica]. Estados Unidos: Warner Bros.

12. Feldman CK (productor), Kazan E (director) (1951). Un tranvía llamado deseo [cinta cinematográfica]. Estados Unidos: Warner Bros.

13. Holguín A (2006). Pedro Almodóvar. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra.

14. Méjean J (2007). Pedro Almodóvar. Barcelona: Ediciones Robinbook.

15. Monterde JE (1994a). El melodrama cinematográfico. Dirigido por… Nº 223:52-65.

16. Monterde JE (1994b). Geografías del melodrama. Dirigido por… Nº 224:52-69.

17. Perales-Bazo F (2008). Pedro Almodóvar: heredero del cine clásico. Zer: Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, 24:281-301. Recuperado de http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2885462.

18. Pérez-Rubio P (2004). El cine melodramático. Barcelona: Ediciones Paidós Ibérica.

19. Rodríguez J (2004). Almodóvar y el melodrama de Hollywood. Historia de una pasión. Valladolid: Editorial Maxtor.

20. Seger L (2000). Cómo crear personajes inolvidables. Guía práctica para el desarrollo de personajes en cine, televisión, publicidad, novelas y narraciones cortas. Barcelona: Paidós Comunicación.

21. Sotinel T (2010). Maestros del cine. Pedro Almodóvar. París: Cahiers du cinéma.

22. Spiegel S (productor), Mankiewicz JL (director). 1959. De repente… el último verano [Cinta cinematográfica]. Estados Unidos: Columbia Pictures.

23. Strauss F (2001). Conversaciones con Pedro Almodóvar. Madrid: Ediciones Akal.

24. Suárez JC (2012). La ley del deseo. Revista Latente, 8:123-127

25. Weingarten L (productor), Brooks R (director) (1958). La gata sobre el tejado de zinc [cinta cinematográfica]. Estados Unidos: Metro Goldwyn Mayer.

26. Williams T (2008). Memorias. Barcelona: Ediciones B para Bruguera.

27. Zurián F, Vázquez-Varela C (coordinadores) (2005). Almodóvar: el cine como pasión. Actas del Congreso Internacional “Pedro Almodóvar”. Cuenca: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha.