10.15178/va.2018.143.85-110

RESEARCH

SOCIAL COGNITION STUDY: CLOTHING AND ITS LINK AS AN ANALYSIS ELEMENT OF NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION

ESTUDIO EN COGNICIÓN SOCIAL: EL VESTUARIO Y SU VINCULACIÓN COMO ELEMENTO DE ANÁLISIS EN LA COMUNICACIÓN NO VERBAL

ESTUDO EM CONHECIMENTO SOCIAL: O VESTUÁRIO E SUA VINCULAÇÃO COMO ELEMENTO DE ANALISES NA COMUNICAÇAO NÃO VERBAL

Jonathan Rodríguez-Jaime1 Abogado y psicólogo Institución Grancolombiano Polytechnic University Institution

1Grancolombiano Polytechnic University Institution. Colombia

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to determine whether clothing might be an element of analysis in nonverbal communication (NVC), given that there is currently an academic bias, on the one hand, those who incorporate it in the study of communication and, on the other hand, authors who do not contemplate it, thus that, an hermeneutical study was conducted as a method of elemental ontology, therefore, this article provides a criterion to create a theoretical framework for NVC and clothing as a sub-category, since, by examining experimental studies and looking at scientific literature, it was found that clothing: a) is a non-linguistic sign that sends at least 19 different messages, b) complies with all the structural elements for the existence of NVC c) is present as an expression mechanism in other species, and d) supports the verbal system by executing 5 functions. These results provide the basis for experimental research. In addition, it is concluded that it is a priority for the scientific community to establish a uniformed classification, in order to allow theoretical advancement of these elements at the international level and, through the same language, otherwise, communication sciences, especially in the sphere of NVC, will continue suffering from multiple opposed or inaccurate conceptions, therefore, it is proposed that the acronym (CF) be used to name any factor or issue resulting from clothing as an element of nonverbal expression.

KEY WORDS: Communication theory; nonverbal communication; clothing; communication psychology; social cognition

RESUMEN

El objetivo del presente artículo es dilucidar si el vestuario debe ser un elemento de análisis en la comunicación no verbal (CNV), dado que en la actualidad existe una polarización académica, por un lado, quienes lo incorporan en el estudio de la comunicación y por otro, un grueso de autores que no lo contemplan, así las cosas, se realizó un estudio hermenéutico como método de la ontología elemental, por ello, esta investigación aporta criterios para crear un marco teórico de la CNV y del vestuario como sub-categoría, pues, al examinar estudios experimentales y revisar la doctrina científica, se encuentra que el vestuario: a) es un signo no lingüístico que envía al menos 19 mensajes diferentes, b) cumple con todos los elementos estructurales para que exista CNV c) está presente como mecanismo de expresión en otras especies d) apoya al sistema verbal ejecutando 5 funciones. Estos resultados sientan las bases para continuar con investigaciones experimentales, para que de esa manera, se puedan explorar otros aspectos del vestuario implicados en la cognición social. Adicionalmente, se concluye que es deber prioritario de la comunidad científica, acoger una clasificación uniforme, en orden a permitir el avance teórico de estos elementos a nivel mundial y a través de un mismo lenguaje, de lo contrario, las ciencias comunicativas, en especial en el ámbito de la CNV, seguirán adoleciendo de múltiples concepciones contrapuestas o imprecisas, por último, se propone la sigla (FV) para denominar todo factor o asunto devenido del vestuario como elemento de expresión no verbal.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Teoría de la comunicación; comunicación no verbal; vestuario; psicología de la comunicación; cognición social

RESUME

O objetivo do presente artigo é dilucidar se o vestuário deve ser um elemento de analises na comunicação não verbal (CNV), dado que na atualidade existe uma polarização acadêmica, por um lado, os que incorporam no estudo da comunicação e por outro, muitos que não contemplam, assim se realizou um estudo hermenêutico como método da ontologia elemental, por isso, esta investigação aporta critérios para criar um marco teórico da CNV e do vestuário como sub categoria, pois, ao examinar estudos experimentais e revisar a doutrina cientifica, resulta que o vestuário: a) é um sinal não linguístico que envia ao menos 19 mensagens diferentes, b) cumpre com todos os elementos estruturais para que exista CNV, c) está presente como mecanismo de expressão em outras espécies, d) apoia ao sistema verbal executando 5 funções. Estes resultados assentam as bases para continuar com investigações experimentais, para que desta maneira possam explorar outros aspectos do vestuário implicados no conhecimento social. Adicionalmente, se conclui que é um dever prioritário da comunidade cientifica acolher uma classificação uniforme para permitir o avance teórico destes elementos a nível mundial e através de uma mesma linguagem, do contrário as ciências comunicativas, em especial no âmbito da CNV, seguiram sofrendo de múltiplas concepções contrapostas ou imprecisas. Por último, se propõe a sigla FV para denominar todo fator ou assunto derivado do vestuário como elemento de expressão não verbal.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Teoria da comunicação; comunicação não verbal; vestuário; psicologia da comunicação; conhecimento social

Received: 24/09/2017

Accepted: 30/11/2017

Correspondence: Jonathan Rodríguez Jaime

jorodriguezj@poligran.edu.co

This article is fed by findings exposed in Rodríguez, J. (2015) work carried out by the present author and which is attached to the line of research in Social Cognition of the Psychology, Education and Culture group PEC-PG, also incorporates some theses of the research product: Le facteur anthropomorphe: élément d’analyze dans la communication non verbale ?

Special thanks to my friends Michel Cislak, philologist and master in language sciences at the University of Lorraine, for his suggestions to the etymological framework, Alice Prada doctoral candidate at the University of Paris-V, for his methodological suggestions and to Kerri-Kay Leon

How to cite the article

Rodríguez Jaime, J. (2018). Social cognition study: clothing and its link as an analysis element of nonverbal communication. [Estudio en cognición social: el vestuario y su vinculación como elemento de análisis en la comunicación no verbal]

Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 143, 85-110

doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.143.85-110

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1041

1. INTRODUCTION

For more than half a century, nonverbal communication (CNV) has been studied in multiple pieces of research; there is currently a great deal of new theoretical contributions that contribute to a number of aspects of the human being, particularly in the analysis of their relationships in society (Kwon et al., 2015). For this reason, multiple branches of the social sciences such as: semiotics, sociology, ethology, anthropology, linguistics and psychology have been in charge of examining this issue (Hernández and Rodríguez, 2009).

Despite the existence of several disciplines, there is a vast number of research articles tending to analyze body language, perhaps, because to some intellectuals, CNV is still “any movement, whether reflective or not, of a part or the whole of the body that a person uses to communicate an emotional message to the outside world” (Fast, 1979, p.5, free translation), a stance shared by Guy Cabana, then, this form of expression “illustrates the truth of the spoken words as all our gestures are an instinctive reflex of our reactions that compose our attitude through the sending of continuous corporal messages” (2008, p.21).

However, these conceptions are inaccurate, given that CNV implies, in a general way, “the exchange of information through non-linguistic signs”. (García, 2000, p.21), this includes any element other than words, in contrast, the language of the body is circumscribed only to a specific type of sign (gestures).

Then, resolving the concept of sign, we obtain that this is an element originated by an issuer, which entails a meaning for a receiver (Boutaud, 2004) from this perspective, in addition to the corporal movements, there are other categories of CNV, such as the paralanguage (Birkholz et al., 2013), proxemics (space management) (Hall, 1984) and finally, the “physical look and appearance (nonverbal signals that remain unperturbed such as the shape of the body or the clothes”) (Hernández and Rodríguez, 2009, p.65).

Certainly, these last two elements are the most segregated of scientific specimens, for that reason, they deserve a deeper theoretical development, because in several sections they are only nominated; in fact, the influence of this category on the communicative process is unknown, then, it is necessary to reproduce compendiums that explicitly refer to reliable or updated academic sources., a matter which the works of (Eicher and Roach-Higgins, 1992; Knapp, 1995) lack, works cited in multiple articles on CNV.

On the other hand, conceiving “body shape and clothing” is inaccurate, taking into account the meta-analysis of Little and Robert (2012), Rodríguez and Cislak (2017) or Rodriguez’s (2015) research, where it is observed that those terms must be studied separately, on the one hand, the anthropomorphic factor (1), on the other hand, the clothing, since the process of transmitting information is not exactly the same. Therefore, it is essential to make a conceptual clarification on the last term, so, in order to execute a correct revision by a hermeneutical method, clothing is taken as the category of analysis in this writing, additionally, to achieve a theoretical decantation, elementary ontology, arranged by François Rastier (1998), is resorted to, following three axes 1) creation of a base semantic framework 2) identification of the elements, characteristics and structural classes of the concepts and 3) objective contrast to CNV.

(1) In terms of scientific studies, correlational, experimental research and derivatives.

In succession, it is necessary to emphasize that, on the category of analysis of this article, there is no explicit definition, nor is there a uniform nomination in the academic environment, probably because of the multiple translations of works. On the other hand, clothing as a sub-category is not even included in some contributions, proof of this are the works of (Fast 1979, p.5, De Lavergne, 2010, p.1, Owen, 2011, p.45; Cestero, 2015, page 2, Pons 2015, page 5), so there is no univocity in the scientific community to accept this term as an element of CNV.

The foregoing, although there are pieces of research that include clothing as part of CNV study (Leathers, and Eaves, 2016) and it can be used in the following matters: political analysis (Marín 2014), socio-cultural information (Entwistle, 2002), the expression of the individuality of the human being (Casablanca and Chacón, 2014a), the perception of the winner (Elkan, 2009), even other studies proposed by evolutionary psychologists allow us to know that there is an influence in the evaluation of aggressiveness (Frank and Gilovich, 1988) success (Hill and Barton, 2005) power or control (Stephen et al., 2012).

In general, in this academic corollary, it can be seen that there are possible aspects where clothing is related to the field of human expression, so, to some science makers, clothing is a criterion belonging to CNV, when transmitting messages without making use of words, however, another stance would argue the opposite, understanding that clothing is decoded as any other stimulus, because, first of all, there is no uniform theoretical framework to delimit it, which makes its communicative vocation doubtful. Secondly, it is possible for the brain to decode information of any component of the universe and this is not why we should say that the cosmos is communicating, so what results from clothes or accessories would simply be a phenomenon of sensoperception explained by the theory of Bruce Goldstein (2009).

Due to the above, it can be questioned: Should clothing be an element of analysis for nonverbal communication? Is clothing a component of nonverbal communication? Does clothing emit messages that can be interpreted?

2. OBJECTIVES

In order to answer these questions, the main purpose is to determine if clothing is an element of analysis in nonverbal communication (2). In a subsidiary way, the aim is to identify the ontology of these two concepts, in order to make a contrast between both criteria, all this, when examining the decodable information of the base analysis category of this study (3).

(2) Wording with the conjunction “if” is chosen in order to guarantee objective observance in terms of a qualitative deepening research with exploratory features, welcoming De la Croix (2012, page 118)

(3) The literature is chosen under the theoretical lines of social cognition and the processing of clothing information in social contexts.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Ontological structure of nonverbal communication and clothing

3.1.1. Ontology of nonverbal communication

In the article “Paradigmas da comunicaçâo: conhecer o quê?”, the author makes solid criticisms to those studying the phenomenon of human expression, because, in that work, she stresses that there is latent lack and even lack of interest to unfold a theoretical framework supra -ordinated in the field of communication (França, 2002), since there is not even a unified criterion that circumscribes this area of knowledge, which is why a minimum agreement must be urgently produced in the scientific community to achieve an epistemological breakthrough (Rodríguez and Cislak 2017).

Therefore, it is essential to build on the semantic roots of the concept, since there is no conceptual uniformity, then, etymologically according to the Société Académique pour l’Étude des Langues Romances (SAELR) (2009) (4) nonverbal communication comes from Latin “communicatio” which means “action or effect of transmitting messages” (p.147) not “ Non: no thing” (p.345) and verbal “verbalis: relative to words” (p.563), integrating the factors, it would be defined as the act of transmitting messages without using the words (Rodríguez and Cislak, 2017).

(4) It was studied together with the appendix for other languages (Spanish) and the title of references in that same work.

However, to Eduardo Duarte, communication “we cannot reduce it to the transmission of information” (2003, p.52), since it involves “the activity of articulation through which socially defined participants negotiate concrete meanings in a physical, temporal and social scenario” (Chi-yue Chiu and Lin Qiu, 2014, p.1 free translation) For this reason, Enríquez Eugène defines it as: “the process by which a source of information A tends to intervene on a receiver of information B to provoke in it the appearance of acts or feelings” (1971, p.169, free translation).

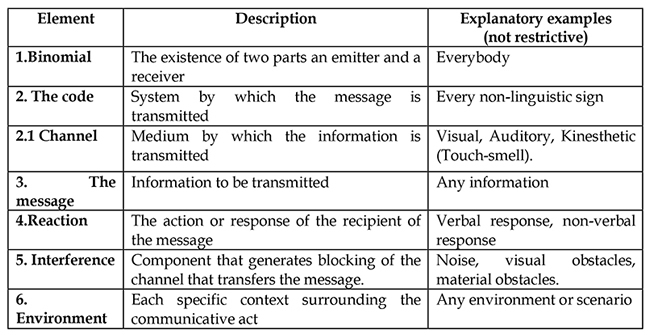

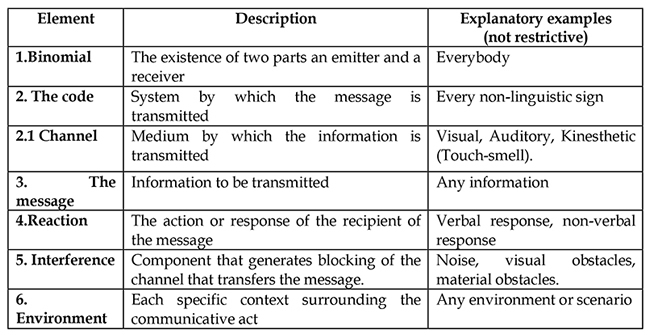

In succession, the work of Guy Spielmann (2011) breaks down a compendium of basic elements that any communicative act contains, then, the form of nonverbal expression complies unrestrictedly with each of these components, as ordered in the following scheme:

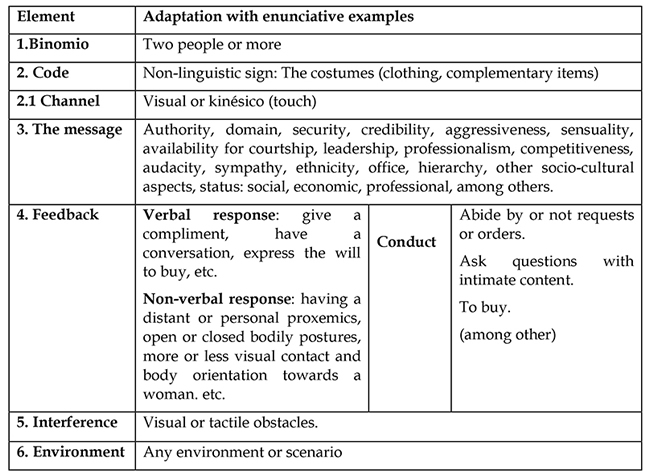

Table 1. General elements of non-verbal communication

Source: taken from Rodríguez (2015, p.5)

Regarding what is presented in the Table 1, there are two special properties of CNV, the first is transfer through a non-linguistic code, therefore, some authors say that a semantic characteristic of this form of nonverbal expression entails the generation of meanings through a behavior different from words (Leathers and Eaves, 2016), so that, there are no official guides governing the use of nonverbal signals, this supports a differentiating property of this communication system and is the traffic of information through signs, which do not contain any syntax or follow grammar rules; which indicates a wide catalog of categories (García, 2000).

Secondly, the channel is the sensory route through which a message travels; in this respect, linguistic communication is based on two channels only, because the spoken language is transmitted through sound and collected by the ears (auditory) or the written coding, the symbols of which belong to the visual and / or tactile scope, of course, only those three are the only means contemplated for sending information in this system. In contrast, CNV uses all five senses, since it is also possible to receive messages through taste and smell (Owen, 2011).

On the other hand, human beings are the only ones with an inherent capacity to abstract thought (Vygotsky, 1962), allowing them to transcend space and time through the use of a number of verbal symbols. Despite this, men are not the only creatures that are able to interact through CNV, so according to Korpikiewicz (2004, p.14) a structural feature of this form of communication is that it is part of several species of the animal kingdom.

On the other hand, the most accurate definition of nonverbal communication is the process between two parties to share any type of messages through a means other than words, that is, expressing information through any non-linguistic code, using the diversity of signs, symbols or other stimuli of that magnitude lacking in syntax, the result of which is a psychological decoding and an immediate response from the receiver. (Rodríguez, 2015, p.7).

Another guiding principle of CNV has been developed by Peter Andersen, in his work Nonverbal Communication : Forms and Functions, because, according to him, this form of expression is irrepressible (2008, p.21), that is to say, that part of its execution is not mediated by conscious processes (Little and Robert, 2012), because there is a connection between the intention to send nonverbal messages and neural circuits responsible for the instincts, within them is the manifestation of emotions, a reason whereby, just as the emotional system is autonomously activated by human biology, CNV also, therefore, shares a large fragment of that brain architecture to encode messages (Buss, 2016), while those mechanisms were developed before the ability to speak and write (Andersen, 2008).

In succession, several aspects of the human being are transmitted without making use of the words, so that CNV is linked to the expression of individuality, then, through its different components, specific behaviors that are translated into personality traits can be evidenced, for example, recurrent bodily manifestations of fear, such as agitated movements, would be an indicator of a person with anxious characteristics (Ekman and Oster, 1981; Fast and Funder, 2008).

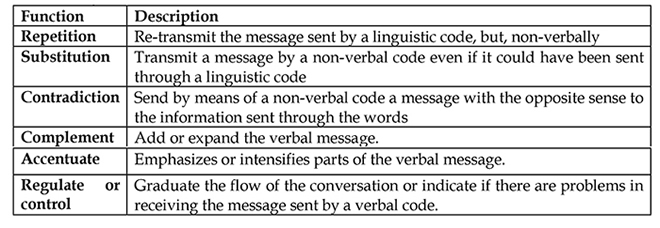

In turn, it is necessary to emphasize that non-linguistic communication does not operate independently of the verbal network, but it “serves to support this system” (Mc Entee, 2004 p.41.), Consequently, CNV plays some functions (5) revealed by Paul Ekman (1965), as organized in the Table 2:

(5) Regarding their execution, authors like Mc. Entee (2004, p.41) and Hargie (2011, p.5 ) add that all functions allow: 1. the construction of a meaning as support for the verbal system or 2. refuting, sending crossed messages, so that, when hermeneutically decanted, it is important to bear in mind that there will always be a relationship with the linguistic network, as a support or contradiction ( Kwon et al., 2015).

Table 2. Functions of non-verbal communication

Source: taken from the work of Rodríguez (2015, p.6)

3.1.2. Ontology of clothing

According to SAELR (6) (2009) the word “clothing” comes from the suffix “ario-arius” which indicates “set” (p.595),it also derives from the Indo-European term “u?es” (p.1019) that in turn conforms the Latin “Vestis” the meaning of which in Spanish is, firstly: “clothes” (7) in second, “costume, clothing” (p.595), those last words have a compound suffix root “mentum” (8) and the prefix “induere” equivalent to “what is worn” (p.178-179), the integration of factors would result in the word clothing being the set of clothes and elements that are worn or that cover the body (9), then, this will be the basic semantic framework for this piece of research.

(6) It was studied together with the appendix for other languages ??(Spanish) and the title of references of proto-Indo-European terms in that same work.

(7) It comes from Latin of the middle ages in three terms: “rauba, ropa, raupa” which mean: “covering with cloth or general clothes” (SAELR , 2009, p.467 ).

(8) This Latin suffix means “means, result or mode” of the preceding term, (SAELR, 2009, p.1178 -a)

(9) The Royal Academy of the Spanish Language (2014) considers for the word clothing ¨ (garments with what one covers one’s body) ¨ consulted from: http://dle.rae.es/?id=bhgK1nm on December 9, 2016

However, it is plausible to have observance of the doctrine, then, clothing is a term studied from the word “dress”, which has been examined by several academics, one of the most influential ones are professors Joanne Eicher and Ellen Roach- Higgins, who make a synthesis of social science trends to achieve a definition, so that, according to the authors, this concept is “a set of body modifications and / or supplements exposed by a person in communication with another human being” ( 1992, p.15).

From the previous definition, two elements can be abstracted, on the one hand, the corporal modifications, which in the judgment of the academics, are alterations imposed directly on the body and include:

Body parts that can be modified, including hair, skin, nails, musculoskeletal system, teeth and breath. Parts of the body that can be described in terms of the specific properties of color, volume and proportion, shape and structure, surface design, texture, smell, sound and taste (Eicher and Roach-Higgins, 1992, p. 16, free translation).

On this aspect, Kim Johnson and Sharon Lennon in their work, The Social Psychology of Dress, expose that corporal transformation conceives, likewise:

Make color changes (for example, the use of cosmetics, tanning, tattooing), the shape (for example, diet, exercise, cosmetic surgery), texture alteration (for example, using lotion to make skin soft), and smell (for example, the use of perfumes, deodorants)” (2013, p.13 free translation).

However, it is essential to specify that the meta-analyses of Little and Robert (2012, p.787), Rodríguez (2015, p.12), Rodríguez and Cislak (2017) or the research by Leathers and Eaves (2016, p. 156), Elliot et al. (2010), Rhodes (2006), among others, point out that the direct effects of changing the body in orbits of color, volume, size, shape or proportion are a different spectrum and are not accepted in terms of “clothing” since, as it was seen in the etymological substrate, that word implies “to wear or be covered”, therefore, it is inconceivable to think, for example, that the physical body modification resulting from a surgery, scar, tooth whitening or a change in the skin by solar radiation mean wearing something (10) rather, that aspect should be strictly circumscribed as a topic of analysis of the anthropomorphic factor in nonverbal communication (11), for this reason, these properties are not included in this ontological analysis and it is necessary that the academic community reflect by updating these postulates.

(10) Nor be covered by something.

(11) Nor be covered by something.

In turn, although Johnson and Lennon (2012) in an attachment to the theory of Eicher, J. and Roach-Higgins M., contemplate “smell and taste” in the category of “clothing - dress” (the original reference of which in English is “Dress”), it is not possible to conceive in the Spanish Language that “someone is wearing an odor or a taste”, therefore, this conception cannot be universally contained in that word, so that the sciences that deal with the study of communication should also wield the creation of a category that responds as a supra-ordinate concept of “smell and taste”, since, being nonverbal stimuli, they are properties that deserve to be introduced in a special classification, since the proposal of the professors does not comply either with the semantic roots exposed herein or with the meta-analyses referred to in the previous paragraph.

Therefore, it is a priority duty of the scientific community to accept a univocal classification, in order to allow the theoretical advance of these elements worldwide and through the same language, otherwise, the communication sciences (especially in the field of CNV), will continue to suffer from multiple opposing or imprecise conceptions, such as those that emerged in the previous section.

On the other hand, the second formulated element is developed by Johnson and Lennon as supplementary factors, which are the devices that are added to the body, such as: “jewelry, clothes, Ipods, makeup, electronic devices, inlays and a wide range of accessories “(2012, p.3 free translation).

Regarding this category, it can be deduced that it complies in a general way with the etymological and semantic reference being the foundation of this writing, a reason why it is still indispensable to generate deep observance of these properties, since man is the one who creates them and even accepts the free use of some of them, a situation that implies the interaction of cognitive processes (Richard et al., 1990). While clothing is also a universal human behavior (Lynch, 1989, Gamble and Gamble, 2017).

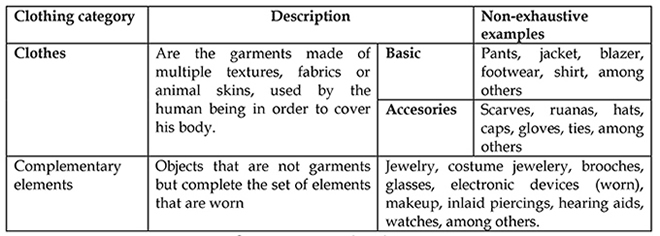

On this basis, a decantation of the structural properties of the concept of clothing is formulated, as shown in the following scheme:

Table 3. Costume properties

Source: own authorship

In summary, Table 3 shows the essential features of clothing: 1) They are elements the origin of which is external to the body and 2) they must be seen outside the skin, although they may be embedded in it. Hence, aspects such as body hair or hair should not be included in this category of CNV, as it happens inaccurately in ( Gamble and Gamble, 2017, p.102 ).

On the other hand, clothing has several functions, the first, to protect from the impact from the physical environment and, therefore, as a means of adapting to the environment (Casablanca and Chacón, 2014b), a timely example includes the use of gloves to protect hands from the cold or the use of shoes to avoid wear on the foot soles (Entwistle, 2002).

Secondly, it acts as a sign between the individual and the broad socio-cultural environment, here you can find elements the use of which is exclusive to an ethnic group or that is given a mystical power, it also serves as a camouflage, a reflection of the state of mind and even social status (Volli, 2001, Gamble and Gamble, 2017). Ultimately, it makes it possible to express information. (Davis and Lennon, 1988, Leathers and Eaves, 2016).

3.2. Information coming from clothing

3.2.1. Color and shape assessment: review of studies in psychology

There is a direct relationship between clothing and its influence on the characteristics people infer from others, its impact is such that it manages to intervene in how others behave, a clear example is developed by Hill and Barton (2005), then, they found an effect produced by color as a stimulus coming from clothes, which was associated with success cases in four combat sports during the 2004 Olympics, this is explained, according to Fetterman, Liu, and Robinson (2015), because any chromatic range “conveys psychological meanings” (p.106, free translation) and even correlates with certain personality traits (see 2015, page 113).

Wiedemann et al. (2012) established that it happens just as in soccer, in their study, the red color is related to the team’s success, it also comes as a factor that increases the odds of getting a win and, if used on one’s own uniform, it can increase the level of confidence at the time of facing a penalty or free kick. To the above, we add the provisions of Hill and Barton (2005) who state that red clothing is linked to self-perception of security, strength or power, for those who wear it and correlatively, decreases confidence in their opponents.

On this basis, it is necessary to show that research indicates that the red color has an activating effect of the sympathetic system (12) of the body (Fetterman, Robinson and Meier, 2012; Elliot and Maier, 2014). Therefore, it is linked to the perception of authority, alert behavior and even has links increasing the assessment of submission to whoever wears garments of that color, since this element has a relationship with control (Rowe et al., 2005) and aggressiveness (Stephen et al., 2012) from an evolutionary perspective. However, there are other colors that are also decoded by the brain as a message of authority, on this basis, Frank and Gilovich (1988) conclude that black uniforms make a referee perceive a hockey or football team as more aggressive.

However, the color of clothing is not limited only to the sports field, but it can increase the perception of success and improves the attractiveness score, since it influences both the user and the recipients of information (Roberts, Owen and Havlicek, 2010). On the one hand, regarding the increase in attraction, heterosexual women prefer men who wear red in clothing, because they link it with a high status (Elliot et al., 2010), power ( McMillan et al., 2002) and even physical fitness to mate (Little and Robert 2012).

(12) It is the nervous system that puts the body in a state of alertness, stress or emergency. Its function, although autonomous, can be increased or decreased by the cerebral cortex.

In a similar way does it happen with women who wear shirts of that same tone, because it positively influences the behavior of men toward them in a romantic-reproductive sense (13) (Elliot and Niesta, 2008), increasing the probability that male people are in the mood of talking (14), feel close to them or even ask them more intimate questions (15) (Kayser, Elliot and Feltman, 2010).

(13) According to an experiment where men stated that they preferred a woman wearing a red shirt to have a date or invest more money in that activity, this as a result of two comparison situations (red vs green and red vs blue, ( Elliot and Niesta , 2008, p.1150)

(14) The behaviors referred to that term are: diminution of the distance between both, open bodily postures, more visual contact and corporal orientation towards the woman.

(15) As a reference, we took the woman wearing the red shirt vs. the women in green or blue in two experimental situations.

Finally, the role played by the choice of clothing to influence social perceptions, particularly in the domain of domination and competition (Davis and Lennon, 1988), which is immersed in a variety of contexts, is notable; however, it becomes very important in the first impression (Thelwell et al., 2010). For example, in studies by Temple and Loewen (1993), it is concluded that women who wear blazer-like jackets were perceived as more expert and with legitimate power, all this being evaluated by people of different gender. (16), additionally, in their research, Damhorst and Pinaire show that the choice of dark suits allows people to make a greater “professional impression” (1989, p.98, free translation) than with other chromatic types, in turn, they conclude that the color of clothes influences the perception of “power, competitiveness and audacity” (1989, p.89 free translation) of other people.

(16) It was researched whether the perceived interpersonal power of a woman is affected by the clothes she wears. With a group of evaluators consisting of 93 male and 68 female undergraduates, through a score ranging from 1 to 4 to drawings of a woman, based on 6 categories (Temple and Loewen, 1993, p.339).

In succession, several academics have developed a framework on the decoding of clothing form. For his part, Ronald Bassett states that there is a certain type of clothing that is perceived as “high status, for example: a tie suit in the case of males or a tailor in women” (1979, p.282, free translation) even in several articles, people who wear that type of attire were more successful in getting strangers to fulfill a requirement requested by them. The opposite effect occurs with people who wear other elements that are associated with “low status such as jeans or work shirts” (1979, p.282, free translation), so, whether by a psychological, socio-cultural vision or by interpretative disposition of semiotics, there are garments linked to the message of authority, credibility or persuasion (Kaiser, 1990, Gamble and Gamble, 2017).

This can be proven by studies collected by (Bassett, 1979, Pornpitakpan, 2004) where people with “high status” clothes emanated messages of authority, because, when demanding others to fulfill a request, the latter complied with it decided to: a) make changes, b) accept pamphlets, c) sign petitions, d) explain directions on the street, e) write the answers to a questionnaire. In contrast, “low status” clothing is associated with messages of low credibility, which results in a low rate of compliance in the same tasks.

O’Neal and Lapitsky (1991) conducted a study to research the effects on credibility scores and declared purchase intent, through the manipulation of clothing worn by a message source, in an advertising situation (17). That article concludes that, when the person was dressed appropriately (18) for the task demonstrated in the advertisement, the subjects of the experiment evaluated it with a significantly greater credibility, which resulted in a directly proportional increase in the purchase rate, therefore, clothing transmits information that can be contrasted with the general stimuli of the context, in order to discriminate them according to their meaning (filter) and, if it finds them coherent, the issuer is classified as credible (Pornpitakpan, 2004).

(17) Two types of dress used by the issuer and two advertising situations that were crossed in order to perform a 2 x 2 factorial design were taken as variables. The participating subjects were randomly assigned in the four experimental manipulations (O’Neal and Lapitsky, 1991, p.31).

(18) The term refers to the consistency of messages between the product sold, the professional setting and clothing.

3.2.2. Assessment of clothing semiotics: socio-cultural information and other associated messages

Clothing is developed as a sign between the individual and their socio-cultural environment, finding a multiplicity of elements the meaning of which is built by a group of people, this is given at an ethnic, local or international level; therefore, from an anthropological perspective, clothes and even the complementary elements emit information, which is encoded in a recent and historic way (Volli, 2001; Casablanca y Chacón, 2014b), allowing the community to interpret them, either through a process of voluntary or unaware registration, which in summary, according to Kaiser (1990), allows clothing to ”transmit socially desirable meanings” (p.25, free translation) “derived from cultural experience” (p.238, free translation).

In succession, you can find parts of clothing that are given a mystical power or the use of which is exclusive to an ethnic or social group, such is the case of certain communities where Brahmins wear hanging oracles with stones that give them special powers (according to beliefs of that culture) which translates into hierarchical power (Volli, 2001). Another current example is the cassock, the priest’s own garment, which gives them an association with religious-spiritual matters, likewise, a chain in the form of a cross or crucifix also provides them with that message of divine connection. In turn, white garments in multiple cultures are associated with sanctity and purity (Heller, 2004), so that this information becomes an attribute of the person wearing it.

On this effect, Johnson, Schofield and Yurchisin (2002), in their study Appearance and Dress as a Source of Information: A Qualitative Approach to Data Collection, examined the content of the answers (19) of a group on the evaluation of the appearance of another, it is concluded that the analysis of clothing is a primary source to perform the execution of that task, likewise, most of the participants considered that the decoding of the information of appearance and general dress are signals that create an impression, the accuracy of which uses the situation or context, they are related to the specific signals emitted by the image of the person.

(19) The qualitative research was carried out including, among others, the trend analysis and their grouping.

At the same time, the dress is an indication of “belonging” (Casablanca and Chacón, 2014b, page 61), for this reason, clothes have the ability to communicate matters such as: nationality or ethnicity, since there are types of clothing that are exclusive to a geopolitical space, for example, turbans indicate that the person who wears it is from the middle east, the same happens with a niqab (20) or an Afghan burka (21), which, in addition to indicating the region of provenience, allow us to know the gender, since, these garments are exclusive to Muslim women. The same happens with the skirt, the use of which in Western society is linked to the female sex (Gamble and Gamble, 2017).

(20) Oriental garment that hides the entire body and face.

(21) Muslim garment that covers the entire body and has an opening (at eye level) that allows you to see.

Another aspect is the socioeconomic status that can be interpreted thanks to the “use of specific garments” (Kraus, Piff and Keltner, 2011 et al, p.246 free translation) is, for example, if a person wears a suit made of silk, cloth which is very fine and therefore very expensive, it will be understood that whoever wears it has much purchasing power.

In the same way, it happens if someone wears a watch inlaid with precious stones or made of gold, this type of item has a value appraised in thousands of dollars, so an individual in poverty could not buy it. However, a more everyday case is given thanks to the brands, some of which have very high prices, so by just seeing these symbols in another’s clothing, their financial level is evaluated, because they transmit the message of wealth (Owyong, 2009; Gamble and Gamble, 2017).

Anthropologically, clothing or its accessories can describe factors such as age or group identity, an example is given with the urban tribes who have special clothing that characterizes them and differentiates them from each other, at the same time, clothing also communicates information about the professional hierarchy (Entwistle, 2002) and even “who controls who” (Nathan, 1989, p.39) such is the case of the military who have medals and attachments that identify the chain of command or its ranks at a glance .

Another example is given by the uniform of the maids, attires that are exclusive to the hotel service staff, it indicates that they perform specific cleaning functions, so that a guest would not go to the manager to ask him to perform hygiene tasks.

3.2.3. Coding of messages through clothing : theory of the 7 universal styles

Alice Parsons (2008), in her book StyleSource: The Power of the Seven Universal Styles for Women and Men, makes a compilation of her theories proposed since the beginning of the 1990s, this one deals with 7 universal types of classifying the information coming from a person or institution, this conception has an application emphasis in the categorization of people’s clothing, which is linked to the transmission of messages.

Although this reservoir of axioms has not been subjected to a thorough review by the traditional disciplines of the social sciences, for more than twenty-five years this theoretical body has served several professions related to the field of communication (such is the case of image consultants, organizational psychologists, designers, public relations specialists, semiologists, among others.) whose purpose is to ensure the coherent transmission of information, which is particularly useful when creating the reputation of artists, politicians or companies and in their interaction with their audiences (Aguilar, 2015).

Then, this theory is based on the expression of individuality (Casablanca, and Chacón, 2014a), whose messages as well as “personality remain stable over time”, (Polaino-Lorente et al., 2007, p.19), the reason why it is possible to organize them into categories. The first is natural or casual, which is characterized by sending information of little structure, relaxation, dynamism, joy or optimism , through elements that, in terms of clothing, can be: handicrafts, worn clothing, jeans, tennis, light colors or from nature (such as green) and even with clothing that is generally loose, light and vaporous (Parsons, 2008).

In second term is the traditional type, the characteristic messages of which are: credibility, loyalty, maturity, responsibility, immutability and a special attachment to traditions, hence its nomination, therefore, it makes use of garments such as suits, ties, classic dresses, with generally sober colors, so that their risk is to communicate being old-fashioned, something that does not happen with the elegant style, the third factor, which sends messages of: distinction, high status, refinement, confidence, formality and prestige. Although they are characterized by wearing garments similar to the traditional, they differ, because the use of fabrics, shapes or colors and accessories are of high quality and even costly, then, it will never transmit messages of archaic presence, rather its risk is to look pretentious (Parsons, 2008).

In fourth term is the romantic style, who generally wear for example: soft, cushioned fabrics, warm colors, laces, some with heart prints or discreet accessories like small pearls, with this they seek to communicate: softness, tenderness, affability and care. Opposedly, there is the seductive type, the characteristic messages of which are: sensuality, stimulating physical care, extroversion and even a seductive attitude, all this, through fitted clothing, necklines, fabrics that leave the body or its silhouettes exposed, textures such as leather and colors like red, on this aspect, works like the one by Leather and Eaves support the sense of this theory, as, in certain tribes, wearing accessories on the head, nose or neck serve to attract the opposite sex or express that they are “available” (2016, p.157) to start courtship.

On the other hand, the sixth style is the dramatic, characterized by sending messages of avant-garde, sophistication, urban, fashion, advanced, among others, in terms of clothing, they can use non-classical, modern elements, with colors in trend or using contrasts, icons and fine structures, which is why their risk is to be perceived as aggressive and intimidating (Parsons, 2008).

In the last place is the creative archetype, which communicates to be imaginative, novel or varied, through garments, accessories, textures and unique colors, without respecting the parameters used by the majority. Here also are contained the urban tribes that arise creating new elements, thanks to the fact that clothing is contemplated in the doctrine

As a means of expressing opposition to the core values of society at a particular stage. That protest, which is reflected in clothing, sometimes allows us to communicate an alternative lifestyle, such is the case of hippie clothing (Saulquin, 2010, p.71).

This allows us to deduce that people can choose to wear items in order to communicate that they do not agree and even that they oppose the status quo and the established standards, as is the case with Punk clothing especially in the 1970s, wearing untidy clothes contrary what was common (structure-sobriety when dressing) expressed their aggressiveness towards the system (Leathers and Eaves, 20 16).

3.3. Clothing, an element of analysis in nonverbal communication

The studies of the previous section allow us to synthesize that when two humans interact, the brain of one with respect to the other, decodes information coming from clothing, giving it a meaning, and then generating an immediate response, this obeys all the indispensable elements so that there is a communicative act in the terms of Spielmann (2011), as shown in the following scheme:

Table 4. Suitability of clothing in the elements of communication

Source: own authorship

The previous scheme shows that clothing transmits messages without the use of words, thus fulfilling what is contemplated in the etymological substrate of CNV; therefore, the information coming from clothes or accessories has a meaning, since it does not go in a straightforward or meaningless way (Gamble and Gamble, 2017), but its individual or collective interpretation produces a range of responses subject to particular interests, personality or other property derived from the receiver’s cognition (Richard, et al 1990; Kraus Piff and Keltner et al., 2011).

Despite the above, to certain authors, it is necessary to articulate a voluntary encoding of the message, that is, the intention to express (Chi-yue Chiu et Lin Qiu, 2014), otherwise, it would be in the presence of a mere act of sensoperception. However, in the field of body language and particularly micro expressions, muscle movements appear without the will of the issuer, which proves that there is not always a conscious communicative vocation, so, this way, clothing can also be classified as an element that belongs to the communication process.

3.3.1. Clothing and nonverbal communication in the animal kingdom

According to Honorata Korpikiewicz, CNV “is innate and widely used by all animals” (2004, p.14), which means that it is not exclusive to humans, regarding this aspect, we must specify that clothing emerges as a manifestation of the cultural development of the human being, like the system of linguistic expression; however, it is possible to find similar mechanisms in other species.

Together, studies by Burley, Krantzberg and Radman (1982) and Cuthill, et al. (1997) conclude that to artificially add some element of red color to a bird (for example, attaching a ring of red plastic to its leg) (22), increases the amount of hostile behavior of this organism. The explanation of this effect occurs because, in violent confrontations, the exposed blood is red, therefore, the others perceive it as more aggressive (23) and consequently act more submissively. This situation is similar to the effect produced by this chromatic type in clothing and its association with dominance or aggressiveness (Hill and Barton, 2005, Wiedemann et al., 2012, Fetterman et al., 2015).

(22) The ring or plastic element of red color would act as an accessory, a sub-category of clothing.

(23) El The red color of the blood resulting from a violent action can explain the association of that chromatic type to aggressiveness, they would be lags of the primitive human brain applied to clothing (Daly and Wilson, 1999)

The same happens with taxonomic types closer to the human race such as the primates of the genus Mandrillus sphinx, where some males have a red coloration that is also associated with the perception of aggressiveness or dominance (Setchell and Wickings, 2005), although this effect comes from the body coat (24),that is, another element of CNV (the anthropomorphic factor) (Rodríguez 2015, Rodríguez and Cislak, 2017), the mechanism of visual interpretation is similar to that resulting from clothing.

(24) Fur, being an element of the body and not a garment that implies wearing something, should not be considered clothing although authors such as Eicher and Roach-Higgins (1992) or Johnson and Lennon (2012) do accept it in that category. The analyses by Little and Robert (2012, p.787), Rodríguez, J. (2015, p.12), Leathers and Eaves (2016, p.156) or the research by Elliot, et al. (2010); Rhodes, et al. (1998) support this differentiation.

Thus, from the point of view of comparative psychology (25) these pieces of research support the thesis that clothing should be specifically accepted as an element of analysis in CNV, then, the clothes or their accessories work as a tool of nonverbal expression, thanks to supra ordinate mechanisms present in the animal kingdom.

(25) Then, “the study of species close to man allows understanding of several cognitive and behavioral processes of the human being” (Maestripieri, 2012, p551, own translation), a subject particularly relevant to the analysis of nonverbal communication.

3.3.2. Clothing: executor of the functions of nonverbal communication

According to Mc. Entee (2004, p.41), a structural aspect of CNV is that it goes interdependently supporting the verbal system, all through six functions shown in Table 2, so, examining their execution in clothing, we find that the repetition function can be carried out if, for example, a subject says, “I’m a professional” and at that moment he is wearing a tie suit or a dark colored tailor, then, according to Damhorst and Pinaire’s research, (1989, p.89), that garment communicates competitiveness, expertise or professionalism, this way, the same message is transmitted, both verbally and nonverbally.

On the other hand, the task of substitution is fulfilled in an exemplified way when urban tribes decide to wear certain clothes to express opposition, avoiding wearing the clothes that most members of society wear (Saulquin, 2010), thus, wearing any item that breaks the classic is a sign to show disagreement and rebellion with everydayness.

Another way to perform this function is to make use of symbols the meaning of which is collective. Thus, if a person wears, for example, a gold ring on the ring finger, it means that he is married; or if you wear a pink ribbon, it indicates that you are engaged in the fight against breast cancer. Then, information is sent through a non-linguistic code, although the words could be used to transmit the message.

Regarding the work of contradiction, this can be evidenced in a case where a person verbally says to be accessible or peaceful, however, he wears a red garment and, by virtue of the studies by Little et al. (2011, p.1642) or that by (Stephen et al, 2012, p.571), it is known that this chromatic type is interpreted by the brain as aggressiveness, which refutes the message sent through the words.

On the other hand, if an individual says: “I have money”, however, at that time he wears clothes with visible brands of international designers or even jewelry with precious metals, then, it follows that the interlocutor will know that whoever spoke not only has money but he has it in large quantity (Gamble and Gamble, 2017), then, clothing extends the verbal message, adding more information to what is expressed orally, this fulfills the task of complementation.

It is possible to execute the task of accentuation by being supported in the corporal moves, for example, if someone says: “I’m from (x) ethnic group, this is what I am” and firmly grasps his characteristic cultural dress, this way he would be intensifying his nationalist verbal expression; however, wearing accessories can also enhance messages, a case would be to use instruments that visually lead to a neckline; a code that can emphasize sexual interest, which is viable according to the vision of Leather and Eaves (2016, p.156), because, in certain societies, women wear ornaments or garments to emphasize that they are available in terms of reproductive mating.

Despite the casuistic development of 5 functions, it is impossible to give expression to the task of regulation by means of examples, since grading the flow of the conversation or recognizing problems in a fragment of the verbal message implies the interaction of meta-cognitive expression skills the higher order of which is applicable specifically to the field of paralanguage or body language.

However, as evidenced in the present text, clothing is part of the communication process through the transmission of at least 19 different messages (see Table 4), in addition, they support the verbal system through the functions of repetition, contradiction, substitution, complementation and accentuation, which is a sufficient basis for clothing to be incorporated into the study of CNV, firstly, because the tasks set forth in Table 2 are not exhaustive, secondly, because the decoded information of the clothes or their complementary elements allow that: a) there is an exchange of messages, b) the receiver constructs a more exact meaning in the communication c) several semantic aspects are fed, as in the kinesic language, anthropomorphic factor and paralanguage.

In succession, since clothing is incorporated into all the structural properties, definition and functions of CNV, then it is feasible to reject the thesis that the information coming from clothing or its complements is simply a process of sensoperception, which serves as a basis for unifying, in the social sciences, the incorporation of this term as another element of CNV analysis, since, having presented the evidence, there are no reasons for some authors to exclude it. Also, it is essential to have deeper observance of this non-linguistic code, to continue experimental research to examine, for example, the theory of the 7 styles and even to evaluate the effects of the texture of a garment in the communicative field and, that way, to explore other aspects of clothing involved in social cognition.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In this text, it was stated that CNV does not have a uniform theoretical agreement and, consequently, neither does clothing as a sub-category, which is why an ontological study of both was made, the result of which allows us to propose that the most eclectic definition of the first term implies the process between two parties to share any type of messages by a means other than words, that is, expressing information through any non-linguistic code, that is, using the diversity of signs, symbols or other stimuli of that magnitude lacking syntax, the result of which is a decoding and an immediate psychological response from the receiver (Rodríguez, 2015).

On the other hand, the term “clothing”, the basic semantic frame of which is: the set of clothes and elements that are worn or cover the body, allowed us to propose an ontological decantation, because in some doctrine they incorrectly incorporated to it elements that are unique to the anthropomorphic factor, an example of this are body modifications, which are accepted by several works derived from Eicher and Roach-Higgins (1992); however, in scientific literature that sub-category is not linked to the word clothing, in addition, its essential characteristic is that it must come from an agent external to the body. Then, after the differentiation, it is proposed that its components be clothes and complementary elements.

Thus, it is a priority duty of the scientific community to accept a unique classification, in order to allow the theoretical advance of these elements worldwide and through the same language, otherwise, communication sciences (especially in the field of CNV), will continue to suffer from multiple opposing or imprecise conceptions, such as those that arose in the previous section, then it is proposed that the acronyms (FV) be used to denominate any factor or issue arising from clothing.

Current works derived from the theory of Eicher and Roach-Higgins (1992) consider “smell and taste” in the category of “clothing - dress” (the original reference in English of which is “ dress “), however, it is not possible to conceive in the Spanish language that “someone is wearing an odor or a taste”, therefore, this conception cannot be universally contained in that word, then, the sciences that deal with the study of communication must also wield the creation of a category that responds as a supra-ordinated concept to “smell and taste”, since, as they are nonverbal stimuli, they deserve to be evaluated and introduced in a special classification, therefore, the proposal of the professors does not comply with the semantic roots presented herein or with the meta-analyses referred to in this piece of research.

In succession, having made a compilation of experimental studies and a review of the specialized doctrine, it is found that the properties of clothing in terms of form and color produce interpretable information, translated into the following messages: Authority, control, confidence, credibility , aggressiveness, sensuality, availability for courtship, leadership, competitiveness, audacity, sympathy, ethnicity, office, hierarchy, other socio-cultural aspects, status: social, economic, professional.

It is also concluded that clothing is a non-linguistic sign, which complies with each of the structural elements for communication to exist, since: (a) it fits the definition of CNV, (b) by means of it different messages are sent, (c) it is possible to find it as a mechanism of expression in other species, (d) it serves as a support to the verbal system executing 5 functions, e) it helps the construction of a more exact meaning, therefore, it can be ruled out that decoding of information from clothing is simply a phenomenon of sensoperception and, therefore, should be incorporated uniformly as an analysis element of CNV.

Finally, it is necessary to have deeper observance of this non-linguistic code, so this article lays the foundations to continue experimental research, so that, this way, other aspects of clothing involved in social cognition are explored, for example, the theory of the 7 styles, the postulates of which continue to be used in several disciplines of communication for more than two decades, without there being an examination by experimental science, there is also a deep development that confirms or discards its axioms, additionally, the influence of texture should be evaluated with empirical bases as another criterion for the analysis of clothing, of which currently there are only functioning hypotheses.

REFERENCES

1. Alicke M, Smith R, Klotz M (1989). Judgments of Physical Attractiveness: The Role of Faces and bodies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12(4):381-389. Doi: 10.1177/0146167286124001

2. Andersen PA (2008). Nonverbal Communication: Forms and Functions. Illinois: Waveland Press.

3. Aguilar D (2015). La tipología del estilo como herramienta clave para mejorar las relaciones humanas a partir los procesos de reclutamiento de personal (Tesis de doctorado). México D.F.: Colegio de Consultores en Imagen Pública.

4. Bassett RE (1979). Effects of source attire on judgments of credibility. Central States Speech Journal, 30(3):282-285

5. Boutaud J (2004). Sémiotique et communication : Un malentendu qui a bien tourné. (Tesis de doctorado). Borgogne: Université de Borgogne

6. Buss D (2016). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of mind, (5ed.) New York: Routhledge.

7. Burley N, Krantzberg G, Radman P. (1982). Influence of color-banding on the conspecific preferences of Zebra Finches (Poephilia guttata), Animal Behavior, 30(2):444–455. Doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(82)80055-9

8. Cabana G (2008). ¡Cuidado! Tus gestos te traicionan, (2ª Ed.) Barcelona: Editorial Sirio

9. Casablanca L, Chacón P (2014a). La moda como lenguaje. Una comunicación no verbal. Revista de la Asociación Aragonesa de Arte, 29(2):1-10.

10. Casablanca L, Chacón P (2014b). El hombre vestido. Una visión sociológica, psicológica y comunicativa sobre la moda. Cartaphilus, 13, 60-83.

11. Cestero A (2015). La Comunicación no verbal: propuestas metodológicas para su estudio. Linred. 13, 1-36. Recuperado de http://www.linred.es/monograficos_pdf/LR_monografico13-2-articulo1.pdf

12. Chi-yue C, Qiu L (2014). Communication and culture: A complexity theory approach. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 17(1):108-111. Doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12054

13. Cuthill IC, Hunt S, Cleary C, Clark C (1997). Colour bands, dominance, and body mass regulation in male Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 264 (1384):1093-1099. Doi: 0.1098/rspb.1997.0151

14. Daly M, Wilson M (1999). Human evolutionary psychology and animal behavior. Animal Behaviour, 57(1): 509-519. Doi: 10.1006/anbe.1998.1027

15. Damhorst ML, Pinaire JA (1989) clothing color value and facial expression: Effect on evaluation in female job applicants. Social behavior and personality, 14(1): 89-98. Doi: 10.2224/sbp.1986.14.1.89

16. Davis LL, Lennon SJ (1988). Social cognition and the study of clothing and human-behavior. Social Behavior and Personality, 16(2):175-186. Doi: 10.2224/sbp.1988.16.2.175

17. De-Lavergne C (2010). La communication non verbale. Recuperado de http://www.univ-montp3.fr/infocom/wp-content/REC-La-communication-non-verbale2.pdf

18. Duarte E (2003). Por uma epistemologia da comunicação. Dans-Lopes MIV. (dir.), Epistemologia da comunicaçâo (2e éd., vol. 1, p. 41-54). Sâo Paulo, Brésil: Loyola.

19. Eicher J, Roach E (1992). Describing Dress: A System of Classifying and Defining: Implications for Analysis of Gender Roles. En R. Barnes & J. B. 9-27

20. Elkan D (2009). The psychology of colour: Why winners wear red. New Scientist, 2723(203):42–45.

21. Ekman (1965). Communication throught nonverbal behavior: A source of information about interpersonal relationship. En Tomkins SS (Ed.), Affection, cognition and personality, (p. 390-492), New York: Springer-verlag

22. Ekman P, Oster H (1981).Facial expressions of emotion. Journal of Psychology, 2(7):115-144. Doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.30.020179.002523

23. Enriquez E (1971). Les Techniques modernes de gestion des entreprises. En Hierche H (2ed.). Communication et organisation, (p.163-179). Paris, France: Dunod.

24. Entwistle J (2002). El cuerpo y la moda, una visión sociológica. Barcelona: Paidós.

25. Elliot AJ, Kayser DN, Greitemeyer T, Lichtenfeld S, Gramzow RH, Maier MA, Liu H (2010). Red, rank, and romance in women viewing men. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General, 139(3):399-417. Doi: 10.1037/a0019689

26. Elliot AJ, Maier MA (2014). Color psychology: effects of perceiving color on psychological functioning in humans. Annual Review of Psychology. 65, 95–120. Doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115035

27. Elliot AJ, Niesta D (2008). Romantic red: red enhances men’s attraction to women. J. Personality & Social Psychology, 95(5). Doi: 1150–1164 10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1150

28. Fast J (1979). El lenguaje del cuerpo. Barcelona, España: Kairos.

29. Fast A, Funder C (2008). Personality as manifest in word use: Correlations with self-report, acquaintance report, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(2):334-346. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.334

30. França V (2002). Paradigmas da comunicaçâo: conhecer o quê?. Dans-Motta LG, Weber MH, França V, Paiva R. (dir.), Estratégias e culturas da comunicaçâo (3e éd., vol. 2, p. 13-29). Brasil, Brasilia: Editora Universidade de Brasilia

31. Frank MG, Gilovich T (1988). The dark side of self-perception and social-perception: Black uniforms and aggression in professional sports. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1):74-85.

32. Fetterman AK, Robinson MD, Meier BP (2012). Anger as “seeing red”: Evidence for a perceptual association. Cognition and Emotion, 26(8):1445–1458. Doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.673477

33. Fetterman AK, Liu T, Robinson M (2015), Extending Color Psychology to the Personality Realm: Interpersonal Hostility Varies by Red Preferences and Perceptual Biases. Journal of personality, 83(1):106-116. Doi: 10.1111/jopy.12087

34. Gamble T, Gamble M (2017). Nonverbal Messages Tell More: A Practical Guide to Nonverbal Communication. New York: Routledge

35. Garcia JL (2000). Comunicacion no verbal, periodismo y medios audiovisuales. Madrid: Universitas.

36. Goldstein BE (2009). Sensation & Perception. San Francisco: Thomson.

37. Hall ET (1984). Le langage silencieux. Paris: Seuil.

38. Hill RA, Barton RA (2005). Red enhances human performance in contests. Nature, 435(239):293-293. Doi: 10.1038/435293a

39. Hargie O (2011). Skilled Interpersonal Communication. New York: Routledge

40. Heller E (2004). Psicología del color. Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili S.A.

41. Hernández M, Rodríguez I (2009). Investigar en comunicación no verbal: un modelo para el análisis del comportamiento kinésico de líderes políticos y para la determinación de su significación estratégica. Enseñanza & Teaching, 27(1):61-94. Recuperado de http://revistas.usal.es/index.php/0212-5374/article/view/6584/7150

42. Johnson KP, Lennon S (2012). Apereance and power: The Social Psychology of Dress. New York: Bloomsbury

43. Johnson KL, Lida M, Tassinary LG (2012). Person (mis)perception: Functionally biased sex categorization of bodies. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Biological Sciences, 279(1749):4982-4989. Doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2060

44. Johnson K, Schofield N, Yurchisin J (2002). Appearance and Dress as a Source of Information: A Qualitative Approach to Data Collection. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 20(3):125-137. Doi: 10.1177/0887302X0202000301

45. Kaiser S (1990). The social psychology of chlothing: Symblolic appereances in context, (2nd ed.) New York: Mcmilan.

46. Kayser D, Elliot A, Feltman R (2010). Fast track report Red and romantic behavior in men viewing women. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 901-908. Doi: 10.1002/ejsp.757

47. Knapp ML (1995). La comunicación no verbal, el cuerpo y el entorno. (4ª ed.) Barcelona: Paidos.

48. Korpikiewicz H (2004). Non verbal communication vs awareness, Lingua ac Communitas, 14(1):13-19. Recuperado de http://www.lingua.amu.edu.pl/Lingua_14/KORPIKIEWICZ_14.pdf

48. Kraus MW, Piff KP, Keltner D (2011). Social Class as Culture: The Convergence of Resources and Rank in the Social Realm. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4):246-250. Doi: 10.1177/0963721411414654

50. Kwon J, Ogawa K, Ono E, Miyake Y (2015). Detection of Nonverbal Synchronization through Phase Difference in Human Communication. PLoS ONE, 10(7):1-15. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133881

51. Leathers D, Eaves MH (2016). Successfull non verbal communication: Principles and applications. (4th ed.), New York: Routledge.

52. Little AC, Robert SC (2012). Evolution, Appearance, and Occupational Success. Evolutionary Psychology, 10(5):782-801. Doi: 10.1177/147470491201000503

53. Lynch A (1989). Survey of Significance and Attention Afforded Dress and Gender in Formative American and English Anthropological Field Studies. manuscript. University of Minnesota.

54. Maestripieri D (2012). Comparative Primate Psychology. Recuperado de http://primate.uchicago.edu/2012CPP.pdf

55. Marín P (2014). La mano encima. Análisis de la comunicación no verbal en la campaña para la secretaría general del partido socialista obrero español. Revista Encuentros, 12(1):93-106. Doi: 10.15665/re.v12i1.204

56. McEntee E (2004). Comunicación Oral. México DF, México: Mc Graw-Hill

57. McMillan O, Monteiro A, Kapan D (2002). Development and evolution on the wing. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 17(3):125-133. Doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02427-2

58. Nathan J (1989). Uniforms and nonuniforms: Communication through clothing. NewYork, Estados Unidos: Greenwood Press.

59. O’Neal GS, Lapitsky M (1991). Effects of Clothing as Nonverbal Communication on Credibility of the Message Source. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 9(3):28-34. Doi: 10.1177/0887302X9100900305

60. Owen H (2011). Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (3rded.) London, England: Routledge.

61. Owyong YSM (2009). Clothing semiotics and the social construction of power relations. Social Semiotics, 19(2):191-211. Doi: 10.1080/10350330902816434

62. Parsons A (2008). StyleSource: The Power of the Seven Universal Styles for Women and Men, (2a. ed.). New York: Universal Style Int

63. Polaino-Lorente A, Cabanyes T, Del-Pozo A (2007). Fundamentos de psicología de la personalidad. Navarra: Universidad de Navarra.

64. Pons C (2015). Comunicación no verbal. Barcelon: kairós.

65. Pornpitakpan C (2004). The Persuasiveness of Source Credibility: A Critical Review of Five Decades’ Evidence. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(2):243–281. Doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02547.x

66. Rastier F (1998). Le problème épistémologique du contexte et le statut de l’interprétation dans les sciences du langage. Language, 98 (129):97-111. Recuperado de http://www.jstor.org/stable/41683254

67. Real Academia de la Lengua Española (2014). Diccionario de la lengua española (23.aed.). Recuperado de http://www.rae.es/rae.html

68. Richard J, Bonnet C, Ghiglione R, Bromberg M, Beauvois J, Doise W, Deschamps J (1990). Traité de psychologie cognitive: cognition, représentation, communication. Paris: Dunod

69. Rhodes G (2006). The Evolutionary Psychology of Facial Beauty, Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 199-226. Doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208

70. Rhodes G, Proffitt F, Grady J, Sumich A (1998). Facial symmetry and the perception of beauty. Psychonom. Bulletin, 5(4):659–669. Doi: 10.3758/BF03208842

71. Roberts SC, Owen RC, Havlicek J (2010). Distinguishing between perceiver and wearer effects in clothing color-associated attributions, Evolutionary Psychology, 8(3):350-64. Doi: 10.1177/147470491000800304

72. Rodríguez J (2015). Aproximación al factor antropomorfo: el cuerpo como estímulo en la comunicación no verbal (Tesis de grado). Institución Universitaria Politécnico Grancolombiano, Bogotá, Colombia.

73. Rodríguez J, Cislak MB (2017). Le facteur antropomorphe: élément d´analyse dans la communication non verbale? Revista CES Psicología, 10(2):126-142.

Doi: 10.21615/cesp.10.2.9

74. Rowe C, Harris JM, Roberts SC (2005). Sporting contests: Seeing red? Putting sportswear in context. Nature, 437(7063):E10-E11. Doi: 10.1038/nature04306

75. Saulquin S (2010). La muerte de la moda, un día después. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

76. Setchell JM, Wickings EJ (2005). Dominance, status signals and coloration in male mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx). Ethology, 111(1):25–50. Doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2004.01054.x

77. Société Académique pour l’Étude des Langue Romances (2009). Dictionnaire pour l´étude avancé des Langues Romances, (2da ed.), (Vols. 1-27), Bordeaux: SAELR.

78. Spielmann G (2011). Théorie(s) de la communication le modèle classique à six éléments. Recuperado de: http://faculty.georgetown.edu/spielmag/docs/comm/commschema.htm

79. Stephen ID, Oldham FH, Perrett DI, Barton RA (2012). Redness enhances perceived aggression, dominance and attractiveness in men’s faces. Evolutionary Psychology, 10(3):562-572. Doi: 10.1177/147470491201000312

80. Temple LE, Loewen KR (1993). Perceptions of power: First impressions of a woman wearing a jacket. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 76:339-348.

81. Thelwell RC, Weston NJV, Greenlees IA, Page JL, Manley AJ (2010). Examining the impact of physical appearance on impressions of coaching competence. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 41:277-292.

83. Vigotsky (1962 ). Thought and Language. Cambridge: MIT Press.

84. Volli U (2001). ¿Semiótica de la moda, semiótica de vestuario?. En deSignis: La moda representaciones e identidad (p. 253-263) Barcelona: Gedisa

84. Wiedemann D, Barton RA, Hill RA (2012). Evolutionary perspectives on sport and competition. In Roberts SC (Ed.), Applied evolutionary psychology (p. 290-307). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

85. Xu Y, Lee A, Wing-Li W, Liu X, Birkholz P (2013). Human Vocal Attractiveness as Signaled by Body Size Projection. Plos One, 8(4):1-9. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062397

AUTHOR

Jonathan Rodríguez Jaime

Lawyer and psychologist of the Grancolombiano Polytechnic University Institution, with academic productions published in both disciplines. In the professional practice, he has worked as a consultant in matters of nonverbal communication of politicians and lawyers. In addition, he has been a speaker at international conferences, where he presents his theses on the anthropomorphic factor or other aspects of nonverbal communication. Currently, he is a member of the research group: Psychology, Education and Culture (PEC-PG), a space in which he conducts studies circumscribed to the area of ??communication psychology.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0636-940X