doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.141.115-137

RESEARCH

INVISIBLE PATRIMONY. RESEARCH LINES FROM A GENDER PERSPECTIVE AND THE RECOVERY OF LGTB MEMORY

PATRIMONIOS INVISIBLES. LÍNEAS DE INVESTIGACIÓN DESDE LA PERSPECTIVA DE GÉNERO Y LA RECUPERACIÓN DE LA MEMORIA LGTB

PATRIMONIOS INVISÍVEIS. LINHAS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO DESDE UMA PERSPECTIVA DE GÊNERO E A RECUPERAÇÃO DA MEMÓRIA LGTB

Antonio-Rafael Fernández-Paradas1 Doctor of History of Art from the University of Málaga, with a doctoral thesis entitled Historiography and methodologies of the History of furniture in Spain (1872-2011). A state of affairs. Graduated in History of Art and Degree in Documentation from the University of Granada. Master of Expert’s Report and Appraisal of Antiques and Works of Art from the University of Alcalá de Henares. He is currently an Assistant Professor Doctor of the University of Granada, where he teaches in the Department of Social Science Didactics of the Faculty of Education Sciences, and he is a teacher of the Master’s Degree in Art and Publicity of the University of Vigo. https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=XoViNywAAAAJ&hl=es

1University of Granada. Spain

ABSTRACT

With the present work, Invisible Patrimony Research lines from a Gender Perspective and the recovery of LGTB Memory firstly starting from the studies of Gender, the own Patrimony and Patrimonial Education about, we try to glimpse new horizons in relation to the treatment, visualization and contributions of women and the LGTB groups into the Patrimonial Fact, and more concretely, how these points of view visualize those Patrimonies, which are invisible for the Society. As a specific objetive, we want to offer a catalog of different options, in a sistematic and orderly way, that allow the analysis of Patrimony, from the sight of Gender and LGTB Studies. In order to reach this aim, we included different lines of investigation, both traditional and modern, that they let the reviewing and interpretation through these perpectives.

KEYWORDS: Patrimony, gender, LGTB, education.Patrimony, gender, LGTB, education.

RESUMEN

Con el presente trabajo, patrimonios invisibles. Líneas de investigación desde la perspectiva del género y la recuperación de la memoria LGTB, partiendo desde los estudios de género, el propio patrimonio y la educación patrimonial, pretendemos vislumbrar nuevos horizontes con respecto al tratamiento, visibilización y aportaciones de las mujeres y los colectivos LGTB al hecho patrimonial, y más concretamente, cómo las aportaciones y miradas de estos visibilizan esos patrimonios que son invisibles para la sociedad. Como objetivo específico, queremos ofrecer de manera ordenada y sistematizada un catálogo de diferentes opciones que permitan analizar el patrimonio desde el punto de vista del género, y de los estudios LGTB, para ello se incluyen diferentes líneas de investigación, tanto tradicionales, como de nuevo cuño, que permiten interpretar el patrimonio desde éstas perspectivas.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Patrimonio, género, LGTB, educación.

RESUMO

Com o presente trabalho, patrimônios invisíveis. Linhas de Investigações desde uma perspectiva de gênero e a recuperação da memória LGTB, partindo de estudos de gênero o próprio patrimônio e a educação patrimonial, pretenderam vislumbrar novos horizontes com respeito ao tratamento, visibilidade e contribuição das mulheres e dos coletivos LGTB ao feito patrimonial e concretamente, como as contribuições e suas perspectivas visibilizam esses patrimônios que são invisíveis para a sociedade. Como objetivo específico queremos oferecer de maneira ordenada e sistematizada um catalogo de diferentes opções que permita analisar o patrimônio desde um ponto de vista do gênero, e dos estudos LGTB, para isso incluem diferentes linhas de investigação, tanto tradicionais, como novas, que permitem interpretar o patrimônio desde esta perspectiva.

PALAVRA CHAVE: Patrimônio, Gênero, LGTB, Educação

Received: 26/04/2017

Accepted: 14/06/2017

Published: 15/12/2017

Correspondence: Antonio Rafael Fernández Paradas. antonioparadas@ugr.es

How to cite the article

Fernández Paradas, A. R. (2017). Invisible patrimony. Research lines from a gender perspective and the recovery of LGTB memory. [Patrimonios invisibles. Líneas de investigación desde la perspectiva de género y la recuperación de la memoria LGTB].

Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 141, 115-137

doi http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.141.115-137

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1068

1. INTRODUCTION

History, rather new histories –those that look at things of a violet color, unfortunately revealed that man made himself important, and therefore the woman, women around the world, fell into deep lethargy . Men told stories of men, their deeds, their exploits and their achievements, until they bequeathed their own Patrimony, which is also a masculine word. The constructions of gender, from the western view of the world, did everything else, assigned social roles to each of the sexes, legitimized by the people themselves, rites of passage were constituted, and the spaces of action of each of the genres as well as their activities and their objects were perfectly demarcated.

People live, struggle and interrelate in geographical spaces, in which they create material and immaterial goods that are legitimized by themselves. These goods are a reflection of their own identity and have been bequeathed to future generations, and we have a moral duty to guard and increase them so that the future inhabitants of the world can enjoy them. However, the problem occurs when the legitimacy of these goods has not been made by society as a whole, that is, by men themselves, but also by women. Pérez Winter (2014, p. 543) points out that “although the estate should include and represent different aspects of the identity of a country or locality, quite often there is invisibilization of some subjects and elements of the identity diversity of a territory.”

With this paper, invisible Patrimony. Lines of research from the gender perspective and the recovery of the LGTB memory, starting from gender studies, Patrimony itself and Patrimony education, we aim to glimpse new horizons regarding treatment, visibility and contributions of women and LGTB groups to the Patrimony fact, and more specifically, how their contributions and looks make those assets that are invisible to society visible. As a specific objective, we want to offer, in an orderly and systematized way, a catalog of different options that make it possible to analyze Patrimony from the point of view of gender; to do so, we include different lines of research, both traditional and new, that allow us to interpret Patrimony from the genre, allowing a

cultural literacy that enables the individual to make a reading of the world around him, raising the understanding of the sociocultural universe and the historical-temporal trajectory in which it is inserted, [which] leads to greater self-esteem of individuals and communities and the valuation of culture understood as being multiple and plural ... [This] critical knowledge and conscious appropriation by communities of their Patrimony are essential factors in the process of sustainable preservation of their property, as well as strengthening feelings of identity and citizenship (Horta, Grunberg and Monterio, 1999, p.6).

If, in all this process of cultural literacy allowed to us by Patrimony education, we exclude women, minorities and LGTB collectives, the reading of the world surrounding us will be incomplete and, therefore, we will continue to privilege some people, their facts and actions over others, we cannot deconstruct gender stereotypes, we will lose a part of our identity as citizens and ultimately, we will be losing exciting pages, written but not read, of our own history.

This paper is structured in different sections. Introduction, objectives and methodology on the one hand, and body of work on the other hand.

In section four, spaces of legality, we provide an overview of the legislative framework of Patrimony, specifically as the issue of gender is collected or not in legislation. In this section, we will also analyze the masculinity of the term Patrimony, as well as the necessary contextualization of Patrimony within cultural rights.

In section five, gender, women and Patrimony, the issues about the absence of women as beings legitimating and producing Patrimony and how heritage has traditionally been legitimized by men are analyzed. We also include reflections on gender as a category of analysis. Finally, a catalog of lines of research is offered to approach heritage from the genre perspective.

In section six, the LGTB look, we offer a panoramic view of the LGTB Patrimony, and as studies related to it are under construction. We also include different approach proposals to study and communicate the LGTB Patrimony.

Finally, the text includes a series of conclusions and a concise bibliography on the topics being discussed and analyzed.

2. OBJECTIVES

1. We intend to glimpse new horizons regarding treatment, visibility and contributions of women and LGTB groups to the patrimonial fact, specifically, how their contributions and looks make those Patrimony that are invisible to society visible.

2. Demonstrate the importance of gender as a category of analysis within Patrimony.

3. Offer an organized and systematized catalog of different options allowing the analysis of Patrimony from the point of view of gender, for this purpose, different lines of research are included, both traditional and new, which allow interpretation of Patrimony from the gender perspective.

4. Analyze the current problems of LGTB Patrimony, as a historical-artistic Patrimony being totally unprotected legally and without actions to ensure survival.

5. Evidence the lack of communication of LGTB Patrimony.

6. Make a catalog of lines of research allowing the researcher to approach LGTB Patrimony.

3. METHODOLOGY

For the elaboration of this piece of research, first a deep historiographic sweep has been made to systematize an important number of publications the object of which is Patrimony, gender and women. The result of this analysis is the systematization of lines of research currently being carried out in relation to Patrimony, gender and women. This process has also allowed us to state what the problems and shortcomings of these publications are.

Secondly, a legislative analysis has been carried out at various levels. On the one hand, international recommendations have been taken into account in relation to women and LGTB groups. On the other hand, the allusions to women and culture by the State Law on Gender Equality and the Andalusian one have been extracted. In relation to the legislative issue, we have thoroughly analyzed the “cultural rights” and put them in relation to the object of study.

Thirdly, we have made a historiographic approach to the LGTB Patrimony issue, both nationally and internationally, especially in the United States.

Finally we have consulted the databases of protected goods in the United States and the Spanish homonyms, which has allowed us to show the presence of LGTB Patrimony in the US databases, and its total absence in the Spanish ones.

4. THE SPACES OF LEGALITY

Patrimony legislation is a dense, complex and not easily accessible topic. Now, we think it is necessary to include a timely reflection on the areas of law and jurisprudence concerning heritage from the perspective of gender analysis, contributions and visibility of women, LGTB groups and minorities.

We start from a terminological conditioning situation, since the term heritage itself is a masculine word, which has been socially legitimated by men who have also projected their worldview onto this term. Secondly, we would have the criticism of legitimizing this Patrimony by way of the male gaze, with the problem of lack of relevant specific legislation. Thirdly, we have the international legislative framework, cultural rights, on which gender studies on h Patrimony should be based and, finally, those statements or normative proposals that specify the importance of Patrimony and its readings by the studies of women, gender studies or feminist studies. We must not forget the different mentions the state law of equality of gender and the laws of the autonomous communities make of women and culture.

Let us start from the beginning, with the Patrimony / marriage binomial. The notion of Patrimony is not only a masculine term, but it is also strongly generalized from the male gaze. It comes from Latin patrimonium, the root of which is Pater, a term laden with social and masculine connotations, by means of which family bonds, hereditarily transmitted goods such as offices, titles or privileges are inherited or constituted. In short, the Patrimony via the firstborn, the foundation of which lies in the Roman law and its Western perpetuation. The concept of Patrimony carries a burden of explicitly intrinsic power, as the one having Patrimony has power, whether family-related, economic, social etc. Meanwhile, the term marriage refers to reproduction and the educational processes of the offspring, establishing a position of inferiority, because women, having no power - Patrimony -, are relegated to the realm of what is domestic and private, from which realm they educate their children. Women, through their patrimony, are also heritagized. This statement, which has a generalist and social historical character, has its exceptions, as for example, in the medieval and modern Catalonia, inheritance rights granted women the possibility of recovering those assets they brought to marriage through their dowry in case of legal separation, which were usually chests and later chests of drawers, among other pieces of trousseau and money.

Once the masculinity of patrimony has been defined, it acquires a new dimension when legitimized by the dominant males, projecting on it a whole system drawing on ideological, political, social and cultural values, from which women were excluded.

The ability to provide value was not, neither is it, universal or accessible to any person but it was associated, and it is associated, with certain social standing: political power, expert knowledge and social relevance, mainly (...) And it is no wonder that women were not included among those subjects socially enabled to activate goods, for the simple reason of their invisibility in public spaces (Martinez Latre, 2009, p. 146).

In their plurality of possibilities, most papers aimed at women and heritage o patrimony vindicate and highlight the contributions made by women, the recovery of historical memory and women’s visibility in relation to equity, an issue about which there is still much to be done, and which is certainly very necessary. The fact that these women and those heritages do not come to light and are not made available to the whole society entails a breach of the basic rights of citizenry, from the point of view of the Declaration of Cultural Rights of Freiburg, in addition to create a discriminatory situation with respect to women.

The Declaration of Freiburg on Cultural Rights was released on May 7, 2007 at the University of Freiburg and later at the Palais des Nations in Geneva, where the cultural dimension of Human Rights was highlighted.

Cultural rights are rights related to art and culture, understood in a wide dimension. They are rights promoted to guarantee that people and communities have access to culture and can participate in whatever their choice may be. They are fundamentally human rights to ensure the enjoyment of culture and its components in conditions of equality, human dignity and non-discrimination. They are rights related to issues such as language; cultural and artistic production; participation in culture; cultural heritage; copyright; minorities and access to culture, among others (cultural rights, nd).

The Freiburg Declaration of Cultural Rights in its article 3 (Cultural Identity and

Heritage) , states the following:

Every person, individually or collectively, has the right:

a) To choose and to respect their cultural identity, in the diversity of their modes of expression. This right is exercised, especially in connection with freedom of thought, conscience, religion , opinion and expression ;

b) To know and to respect their own culture, as well as the cultures that, in their diversity, constitute the common heritage of humanity. This particularly implies the right to know human rights and fundamental freedoms, essential values of that heritage;

c) To access, in particular through the exercise of the rights to education and information, to the cultural patrimonies that constitute expressions of different cultures, as well as resources for present and future generations.

See the full text of the Freiburg Declaration on cultural rights:

http://www.culturalrights.net/descargas/drets_culturals239.pdf

The issue of cultural rights is of paramount importance to understand, access and have the right to enjoy our identity and heritage, but, besides being very much unknown, they develop other problems. The main and most complex one is that the controlling, protecting and guaranteeing mechanisms, as well as the efforts invested in safeguarding them, are substantially lower than those used in the other human rights, such as social and educational rights. In this situation, we must add women’s own invisibility to cultural rights.

Although the struggles of women to achieve equality with men add years to their history, the reality is that the protection of their cultural rights, and therefore of society as a whole, lacks sufficient legal frameworks allowing adequate action on them. Back in 1979, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), “establishes rules expressly regulating equal access in political, labor rights, civil status, family relationships, education, health, but says nothing about cultural rights” (Colombato, 2013: 9). In the case of Belem do Par Convention (Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women, 1994) no reference to the work and cultural practices of women is made, also excluding references to equal cultural participation in their communities. Only one reference in Article 5 prescribes that “any woman can freely and fully exercise their rights under international and regional instruments on human rights. The party States recognize that violence against women prevents and nullifies the exercise of those rights”.

Regarding culture, Law 12/2007 as of 26 November, to promote gender equality in Andalusia, mentions the need to “make visible and recognize the contribution of women to the various facets of history, science, politics, culture and development of society.” For its part, Article 16, related to “curriculum materials and textbooks,” makes reference to the fact that “Andalusian educational administration will ensure that, in textbooks and curriculum materials, cultural prejudices and sexist and discriminatory stereotypes are eliminated, focusing on the eradication of models in which situations of inequality and gender violence appear, valuing those that best respond to coeducation among girls and boys.” Meanwhile, Organic Law 3/2007 as of March 22 for effective equality of women and men, mentions that “all positive actions necessary to correct situations of inequality in production and intellectual artistic and cultural creation of women”.

If the visibility of the cultural rights of women is far from being a reality from the point of view of international law, those targeting LGTB groups are nonexistent. Here again there is a circumstance to be taken into account, while the rights of women in the Western world have been consolidated throughout the 21st century, homosexuality, for example, has been considered a disease until recently, and the rights of homosexuals are in the process of being accepted, even in countries of the European Union itself. Much more delicate is the situation of the transgender, the transsexual, etc., in most cases lacking any kind of legal protection. It is noteworthy that the United Nations Declaration on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (United Nations General Assembly on December 18, 2008), does not make the slightest allusion to the right of LGTB groups, and j society as a whole, to enjoy their own heritage and cultural identity, for whose legal foundation, like that of women, we have to resort to the Freiburg Declaration on Cultural Rights.

5. GENDER, WOMEN AND HERITAGE OR PATRIMONY

5.1. Women and heritage

Consideration of women in relation to equity compulsorily must start from the legal framework we have outlined above, the analysis of which, according to Perez Winter (2014, p 546.) leads us to ask the following questions: “Which identity is being represented and which is excluded and omitted? How is this identity activated and represented in the process of heritagization? “.

Although this situation is gradually being reversed, the reality is that the answers to these questions go through the patriarchal view of the white man, located in a specific cultural context, the Western one, with certain social standing, and political and cultural ideals that he projects on the legitimization of heritage, by means of which he maintains the structures of patriarchy. In this sense, “ heritagization is another mechanism that contributes to shaping and legitimizing narratives of inclusion or exclusion to configure and represent the identity of a community and locality” (Pérez Winter, 2014, p. 546). The consequence of this male gaze would be that of offering an unrealistic and stereotypical view of women, isolating them as culture-producing subjects and placing them in timeless domestic spaces, conditioned by biological theories, sex, and their reproductive and social functions. We had to wait for the twentieth century for the “feminist epistemologists and feminist theories [to give] rise to observing and interpreting how the heritage- and museum-related value of daily life has been activated “ (Martinez Latre, 2009, p. 138).

Therefore, we start on a situation in which women have consistently been removed from public life, relegated to housekeeping, with no presence in the social, cultural and economic life, whose history also has been told by men. To this situation, we must add the epistemological traditions of Social Sciences in general and of History in particular, where, nowadays, there is still prevalence in the textbooks of a positivist, belligerent story that shows history as a succession of political events and battles starring men (Garcia Luque, 2016, pp. 245-254).

It was not until the French Revolution that women wondered what their role was in equality, liberty and fraternity, and it was much longer, in the first third of the twentieth century, when their basic rights began to be recognized. And it was not until mid-century when “national liberation movements rose against colonialism or imperialism, as well as the movements in favor of the gay, the ecology and women” (Lagunas and Ramos, 2007, p. 123). From the heritage viewpoint, these new orders will bring recognition of a specific culture of women.

The next step was to recognize the importance of maintenance activities, and the need to recover and draw attention to women through them. Revealing this was a momentous step because, suddenly, the walls of the household space turned women into perfect vehicles of cultural transmission because “women are often the cornerstone of ethnic transmission, and cultural transmission and reproduction” (Anthias, 2006, p. 50). A vehicle of transmission, but also a historical subject to be considered, and a producer of cultural goods.

5.2. Gender as a category of analysis in the Social Sciences and heritage

The inclusion of gender as a category of analysis has been an important antidote when bringing new life into the great historiographical constructions in the fields of history, art, geography, etc., since it is presented as a privileged position from which we can see the world from a holistic view regarding the dynamics of society and its behaviors, revealing societal organization, but also the hidden mechanisms making the relations between the sexes visible, and their social projections, as well as their close interrelationships with other analytical categories such as class, race or ethnicity.

From the point of view of social sciences, the emergence of “gender as a category of analysis has transformed the interpretation of time and space, which are the two basic building blocks in the construction of social knowledge” (García Luque, 2016, p 249). By overcoming the purely political, belligerent vision and as a successive construct of empirically tested dates and facts, gender “entailed an alternative vision and global rethinking of the great interpretive axis of history” (Garcia Luque, 2016, p. 253). Therefore, thanks to gender, history has been greatly enriched and in some ways surpassed itself, since by including women as a vehicle of production, transformation and transmission, new stories that either completed the previous ones or gave a completely different version of the facts came to be generated, which has necessarily to entail revising the principles and values on which our civilization is based, an issue that in turn will end up being manifested in legislation, textbooks and finally in the own deconstruction of gender stereotypes.

According to Perez Winter (2014), from the point of purely patrimonial view, the views provided from the gender perspective have not only made women visible, highlighting their importance as subjects producing culture and identity, but gender has also become a powerful weapon for the economic development of many populations because, thanks to the analysis of gender in its interrelations, references and interferences between men and women, it has been possible to correct social imbalances and, above all, to understand the internal dynamics of functioning underlying certain cultural groups, “showing the influence of gender on conservation and utilization of cultural heritage, [by] highlighting the importance of integrating social participation of women and men equally to strengthen social cohesion and detonate development processes” (Lugo Espinosa, 2011, p.599).

Knowing the internal reality of a society or population allows us to reveal how women and men see themselves in a certain context, which are the looks projecting over each other, and how they are seen in relation to the heritage they have generated and keep generating, which allows us to take educational, economic measures, etc., in favor of the community and its development, and how these parameters affect the conservation, dissemination and enhancement of heritage. “By encouraging the participation of women and men in the preservation of the cultural heritage with a gender approach, equity is promoted in the community. Cultural heritage can strengthen social and cultural identity and promote gender equality in the community” (Lugo Espinosa et al, 2011, p. 600).

5.3. Lines of research. A proposal for classification from heritage

Wanting to define each of the possible fields of research aimed at women in their relations with heritage is an almost impossible task because any type of activity may be capable of being analyzed from a gender perspective, in addition to having a feminine view of that reality. For our part, in the bibliographic and historiographic review we conducted for this text, we have found lack of jobs giving an overview of how to study women in relation to heritage, since most analyzed texts offer specific actions addressing specific problems from a gender or women’s perspective. With this classification proposal, we intend to compile a series of lines of research based on which heritage has been analyzed in order to provide a systematic and updated tool for teachers, researchers and students on which to build new spaces for reflection.

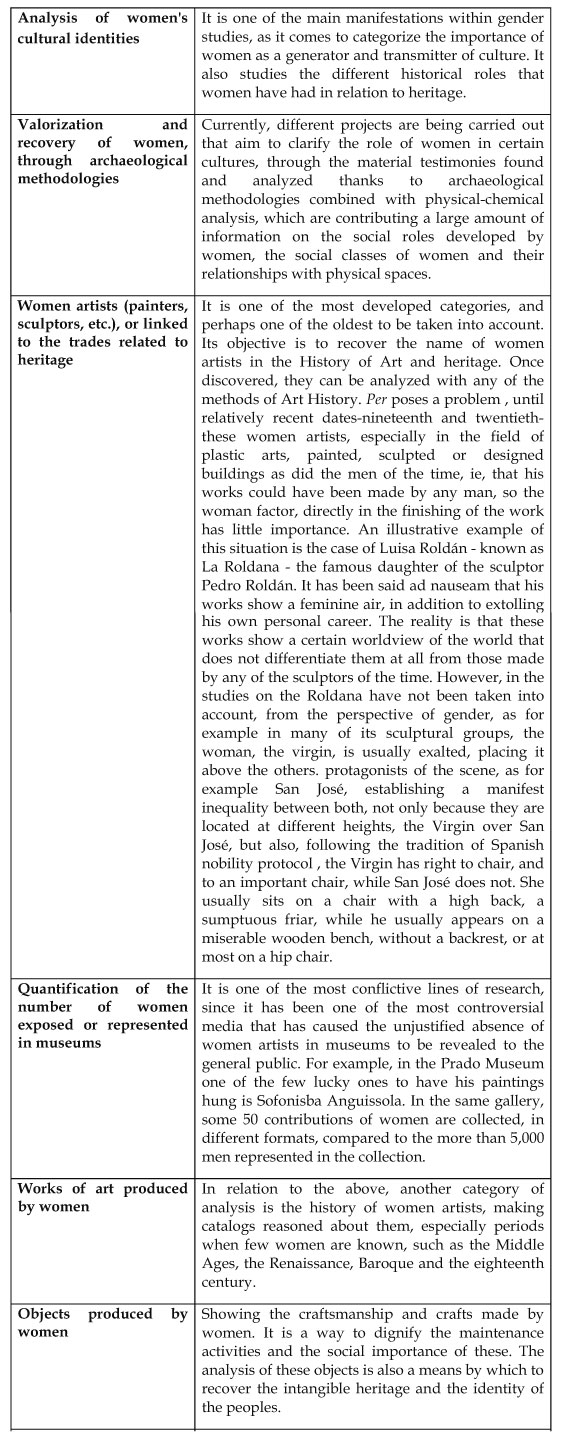

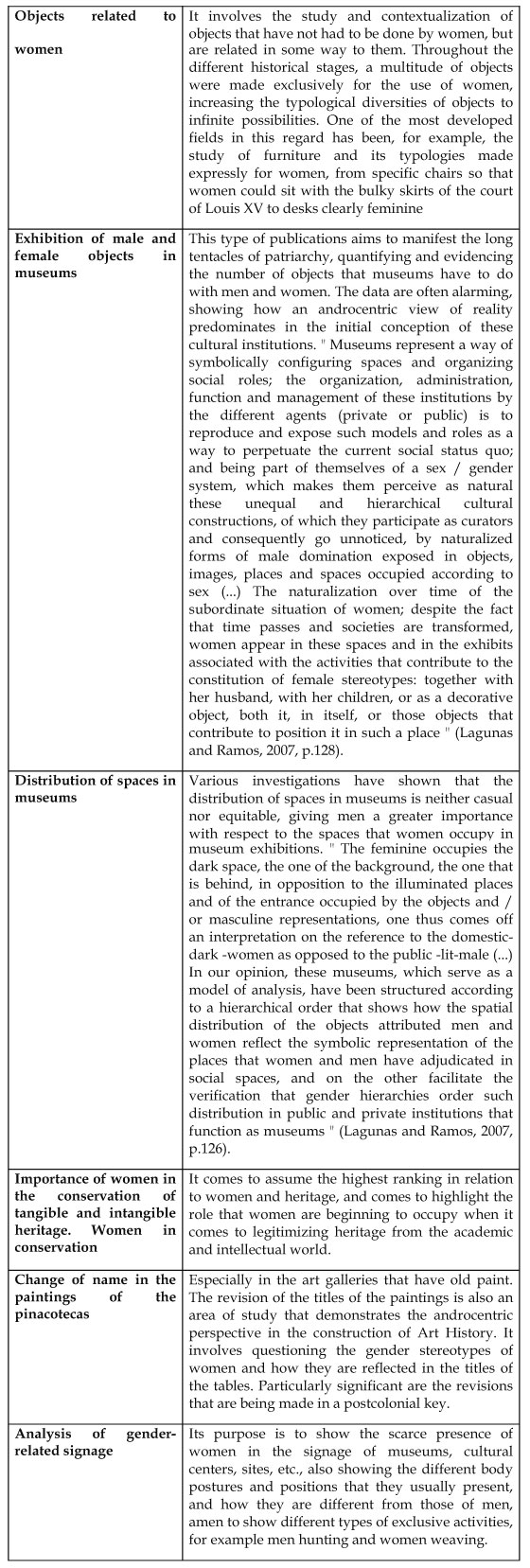

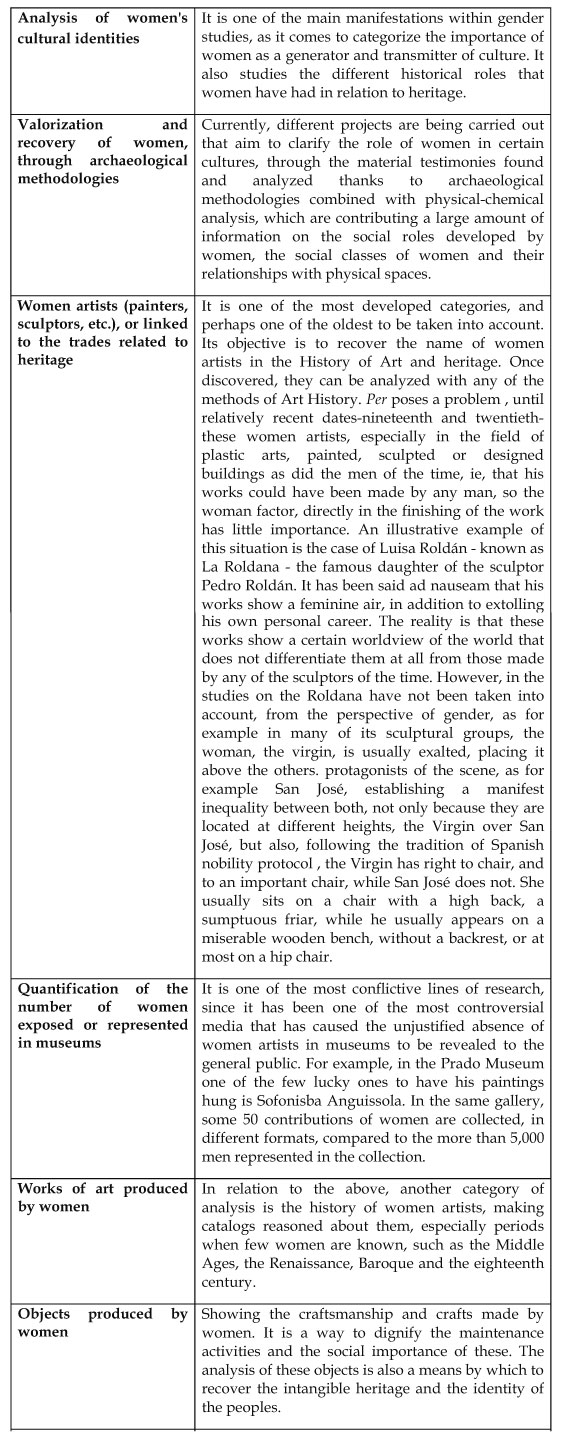

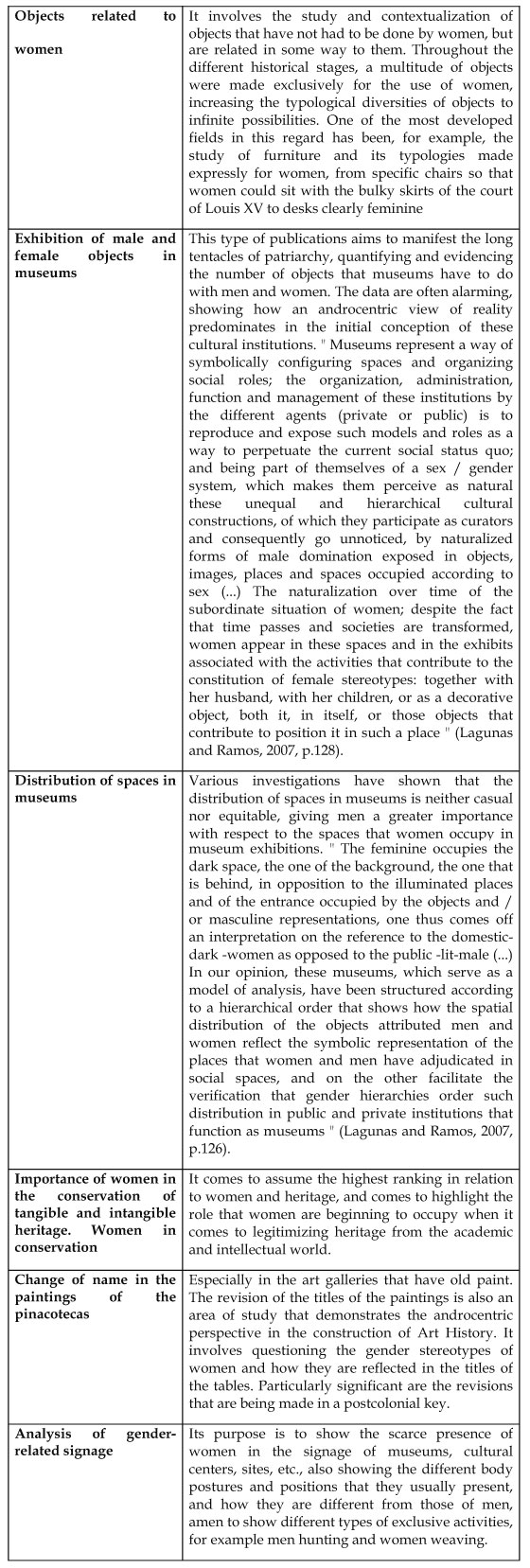

We defined two types of actions. On the one hand, lines of research that specifically aim to analyze heritage from different perspectives and, on the other hand, lines of dissemination, awareness and equity, which aim, once the previous ones have done their work, to demonstrate the heritage contributed by women throughout history.

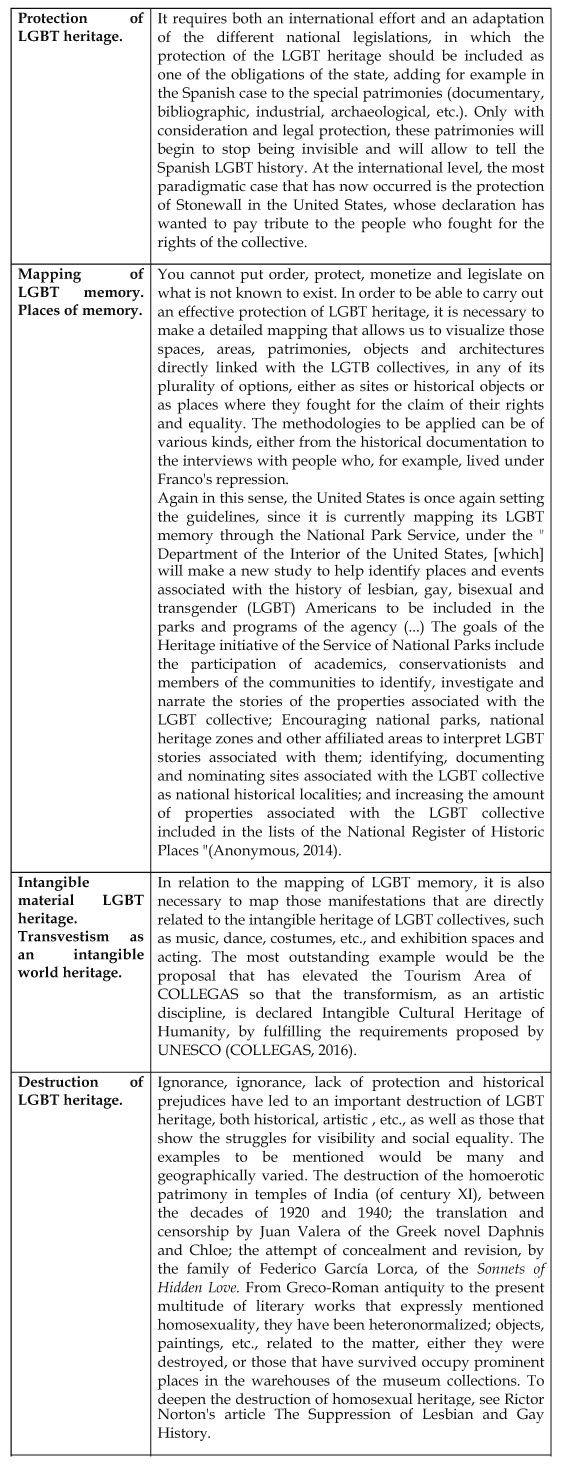

5.3.1. Research lines from heritage

5.3.2. Lines of dissemination, awareness raising and equity

All those issues and proposals that can be carried out once any of the previous research processes has been attained would fall into this category.

6. THE LGTB VIEW

6.1. Invisible subjects

We want to think, from the point of view of the construction of egalitarian modern societies, that if visualizing women in history and at present is a guarantee for equity among people, recovering the LGTB memory, from a patrimonial viewpoint, will contribute to reinforce these objectives, ensuring that no one is discriminated because of their sex, identity or gender.

If, in the case of women, we have been asserting that their heritage and their patrimonial relations have been legitimized by men, the case of LGTB heritages has not yet been legitimized by anyone. Their object-testimonial manifestations are in a legal limbo, which at most is diluted between the artisticity of the testimonies, but they are not categorized as heritages that reveal a new vision of history, in which there were not only women and men, but also homosexuals, lesbians, hermaphrodites, transvestites, etc., and which we understand to be so important to understand ourselves, our history and our circumstances, as they are to study men and women.

6.2. The issue of LGTB heritage or patrimony

We could define LGTB heritage as a set of material and immaterial testimonies that show the participation and importance of homosexuals, lesbians, hermaphrodites, transvestites, etc., in historical societies, as well as manifesting, equally, the processes of discrimination that they have undergone throughout the ages and whose analysis allows us to reconstruct the past in a more exact and approximate way to the cosmo visions of the world of each moment. The retrieval, analysis and protection of the material and immaterial testimonies of these subcultures are equally constructs of equity and social and emotional progress.

To speak of LGTB heritage is to enter a world the foundations of which have not even begun to be traced. It is not that it is an emerging field of study, it is that it is a field that we have not yet questioned to be studied. It is an area of social knowledge, which through LGTB heritage, will allow us to get to better understand our history and also the societies in which we live. From the point of view of communication, LGTB heritage has virtually zero media impact.

As an area of knowledge, it has no history, institutional support, or legal protection, so that we are legally violating the cultural rights to which we previously referred. In Spain, LGTB heritage is not only totally invisible, but also there are no sites of the LGTB historical memory. Nor are there any measures that reverse this situation.

Therefore, the protection of LGTB heritage is a line of work from which nothing has been done, and which disciplinary foundations and criteria for intervention have still to be defined. Preserving, protecting, interpreting and disseminating LGTB heritage means recovering and putting at the service of society its own history. The mistake is to consider these assets, as was the case with women, to be the heritage of women, the heritage of homosexuals, or the heritage of the LGTB groups. From the perspective of cultural rights, society, everyone, we have rights to have each of these assets recovered as an integral part of our social and cultural identity.

From the point of view of approximations to LGTB heritage, we think that there are two well differentiated major historical periods. On the one hand, there are all those objects, assets and tangible and intangible manifestations related to contexts of the past, which evidence the social importance of these groups, and the existence of them, but do not show the struggle to make them visible and achieve equal rights. On the other hand, there would be those manifestations, typical of the second half of the 20th century, which are reflections of transcendental historical moments for the visibility and rights of homosexuals, lesbians, etc.

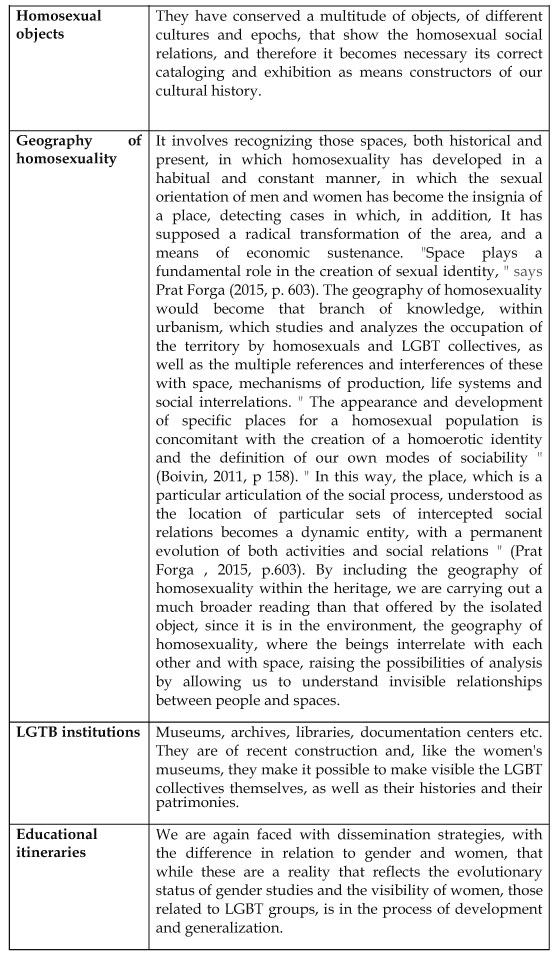

6.3. Lines of investigation

7. CONCLUSION

The historiographic review carried out in relation to gender, heritage and women has allowed us to highlight the different perspectives that are being applied to analyze the relationship between heritage and women. The result of this analysis is the catalog of lines of research that we propose as a basis to give a global vision of the state of the art of these studies.

In the case of LGTB heritage, we have been able to show a much more complex situation, since while the heritage of women has some legal protection, the heritage produced by the LGTB groups and places of historical memory related to them, in Spain, pass for the stage of being a nonexistent reality, a question we have been able to verify by means of historiographically reviewing and consulting the databases of the protected Spanish heritage. This situation has a different perspective, for example, if we compare it with the case of the United States, where the places of historical memory related to LGTB groups are currently being mapped, in addition to granting specific protections to certain spaces and monuments.

The catalog of lines of research we propose in relation to LGTB heritage results from this comparison and analysis.

REFERENCES

1. Anónimo (2014). Colegas propone que el transformismo sea declarado Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial de la Humanidad, COLEGAS. Recuperado de http://www.colegaweb.org/colegas-propone-que-el-transformismo-sea-declarado-patrimonio-cultural-inmaterial-de-la-humanidad.

2. Anónimo (2014). La destrucción del patrimonio Homosexual, L´armari Obert. Recuperado de http://leopoldest.blogspot.com.es/2014/12/la-destruccion-del-patrimonio-homosexual.html.

3. Anónimo (2016). Obama designa primer monumento nacional LGBT de EEUU, La Información. Recuperado de http://www.lainformacion.com/arte-cultura-y-espectaculos/monumentos-y-patrimonio-nacional/Obama-monumento-nacional-LGBT-EEUU_0_929008986.html.

4. Anónimo (2014). Recopilan información para la historia de las personas LGBT, en Estados Unidos (2014). IIP Digital. Recuperado de http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/spanish/article/2014/06/20140604300805.html#ixzz4NGlLqVuD.

5. Anthias F (2006). Género, etnicidad, clase y migración: Interseccionalidad y pertenencia translocalizacional, en Rodríguez P, (Edit.). Feminismos periféricos (pp. 49-68). Granada: Editorial Alhulia.

6. Boivin RR (2011). De la ambigüedad del clóset a la cultura del gueto gay: género y homosexualidad en París, Madrid y México. La ventana, 54, 146-190.

7. Carreño-Robles E (2016). Museos en clave de género. Revista ph, 89, 157-158.

8. Colombato LC (2013). Hegemonías y subordinaciones en el campo de los derechos culturales. Patrimonio cultural, etnicidad y género, Revista Perspectivas, 3, 1-13.

9. Derechos culturales (sf). En Derechos culturales, cultura y desarrollo. Recuperado de http://www.culturalrights.net/es/principal.php?c=1.

10. Díez-Jorge ME (2016). Entre pinceles y andamios: Mujeres en el Arte, en VVAA, De puertas para dentro: patrimonio y género en la Universidad de Granada (pp. 9-21). Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada.

11. Durán-Manso V (2015). La nueva masculinidad en los personajes homosexuales de ficción seriada española: de Cuéntame a Sexo en Chueca, Área Abierta, 15(1):63-75.

12. García-Luque A (2016). El género en la enseñanza-aprendizaje de las Ciencias Sociales, en Liceras-Ruíz A, Romero-Sánchez G (Coord.). Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales (pp. 249-269). Madrid: Pirámide.

13. García-Luque A, Herranz-Sánchez A (2016). Integrando la perspectiva de género en la enseñanza y difusión del patrimonio, en García-Ruiz CR, Arroyo-Doreste A, Andreu-Mediero B (Ed.). Deconstruir la alteridad desde la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Educar para una ciudadanía global (pp. 343-352). Madrid: Entimema.

14. García-Ortega M, Marín-Poot HM (2014). Creación y apropiación de espacios sociales en el turismo gay: Identidad, consumo y mercado en el Caribe mexicano, Culturales, 2(1):71-94.

15. García VQ, Robles LG (2010). El papel de la mujer en la conservación y transmisión del patrimonio cultural, Asparkía: investigación feminista, 21, 75-90.

16. Herd G (1992). Coming out as a Rite of Passage: A Chicago Study, en Herd G (comp). Gay Culture in America. Boston: Beacon Press.

17. Horta ML, Grumber E, Monteiro AA (1999). Guía básica de educación patrimonial. Brasilia: Instituto de Patrimonio Histórico e Artístico Nacional.

18. Lagunas C, Ramos M (2007). Patrimonio y cultura de las mujeres. Jerarquías y espacios de género en museos locales de generación popular y en institutos oficiales nacionales, La Aljaba segunda época. Revista de Estudios de la Mujer, 11, 119-134.

19. López-Fernández-Cao M, Fernández-Valencia A, Bernárdez-Rodal A (2012). El patrimonio de las mujeres en los museos. Madrid: Fundamentos.

20. Lugo-Espinosa G, Alberti-Manzanares MDP, Figueroa-Rodríguez OL, Talavera-Magaña D, Monterrubio-Cordero JC (2011). Patrimonio cultural y género como estrategia de desarrollo en Tepetlaoxtoc, Estado de México, Pasos. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 9, 599-612.

21. Martínez-Latre C (2009). ¿Tiene sexo el patrimonio? Museos.es: Revista de la Subdirección General de Museos Estatales, 5, 138-151.

22. Pérez-Winter C (2015). Género y Patrimonio: Las ‘ProMujeres’ de Capilla del Señor, Estudios Feministas, 22(2):543-543.

23. Prat-Forga JM (2015). Las motivaciones de los turistas LGBT en la elección de la ciudad de Barcelona, Documents d’anàlisi geogràfica, 6(3):601-621.

24. Norton Rictor (2005). The Suppression of Lesbian and Gay History. Recuperado de ttp://rictornorton.co.uk/suppress.htm.

25. Sapriza G, Cherro MV (2016). Generizar el patrimonio. Algo más que objetos creados por mujeres, en VVAA. La memoria femenina: mujeres en la historia, historia de mujeres (pp. 108-119). Madrid: Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones.

26. Serrano MI (2011). Chueca, Calor, color y orgullo gay, en ABC, Recuperado de http://hemeroteca.abc.es/nav/Navigate.exe/hemeroteca/madrid/abc/2001/06/30/090.html.