10.15178/va.2018.144.01-18

RESEARCH

LYRIC VIDEOS: THE MEETING OF THE MUSIC VIDEO WITH GRAPHIC DESIGN AND THE TYPOGRAPHIC COMPOSITION

LYRIC VÍDEOS: EL ENCUENTRO DEL VIDEOCLIP CON EL DISEÑO GRÁFICO Y LA COMPOSICIÓN TIPOGRÁFICA

LYRIC VÍDEOS: O ENCONTRO DO VIDEOCLIPE COM O DESENHO GRÁFICO E A COMPOSIÇÃO TIPOGRÁFICA

José-Patricio Pérez-Rufí1

1Malaga University. Spain

ABSCTRACT

The main purpose of this article is the analysis of the lyric video in order to define the format as a commercial audiovisual creation, to describe the use of formal resources related to the use of the text and, in a second step, to make a classification of the lyric videos in function of the variables considered in the analysis methodology. The lyric video is a subgenre within the music video that represents, through textual codes, the entire verbal content of a song, usually synchronized with that one. Even as a very economical production format in terms of budgets, lyric video has become a popular phenomenon thanks to its distribution through YouTube and other online video platforms. To achieve the proposed objectives, we will conduct a content analysis in a sample of lyric videos, based on a methodology based on the proposals of various authors that address the relationship of audiovisual discourse with textual codes and graphic design. The results of our analysis highlight the graphic and digital nature of the format, in which the recorded film image is rarely used as a formal resource prior to editing. In the same way, the written texts would appear integrated in the discourse in an extradiegetic way and would alternate various typographical sources, usually in movement, in order to achieve a high dynamism and thus seduce the viewer.

KEY WORDS: Music Video; Lyric Video; Graphic Design; Audio-visual text analysis; Kinetic Typography; YouTube; Fandom

RESUMEN

Este artículo tiene por objeto principal el análisis del lyric vídeo a fin de definir el formato como creación audiovisual comercial, describir el uso de los recursos formales relacionados con el uso del texto y, en un segundo paso, realizar una clasificación de los lyric vídeos en función de las variables consideradas en la metodología de análisis. El lyric vídeo es un subgénero dentro del vídeo musical que representa a través de códigos textuales íntegramente el contenido verbal de una canción, por lo general de manera sincronizada con aquella. Incluso como un formato de producción muy económica en cuanto a presupuestos, el lyric vídeo se ha convertido en un fenómeno popular gracias a su distribución a través de YouTube y otras plataformas de vídeo online. Para lograr los objetivos propuestos, realizaremos un análisis de contenido en una muestra de lyric videos, a partir de una metodología basada en las propuestas de diversos autores que atienda a la relación del discurso audiovisual con los códigos textuales y el diseño gráfico. Los resultados a los que llevan nuestro análisis destacan la naturaleza gráfica y digital del formato, en el que

raramente se utiliza como recurso formal la imagen fílmica grabada de forma previa a la edición. De igual modo, los textos escritos aparecerían integrados en el discurso de manera extradiegética y alternaría diversas fuentes tipográficas, por lo general en movimiento, con objeto de lograr un alto dinamismo y así seducir al espectador.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Vídeo musical; Lyric vídeo; Diseño gráfico; Análisis del discurso audiovisual; Tipografía cinética; YouTube; Fandom

RESUME

Este artigo tem como objetivo principal a analises do lyric vídeo afim de definir o formato como criação audiovisual comercial, descrever o uso dos recursos formais relacionados com o uso do texto e, em segundo passo, realizar uma classificação dos lyric vídeos em função das variáveis consideradas na metodologia de analises. O lyric vídeo é um subgênero dentro do vídeo musical que representa através de códigos textuais integramente o conteúdo verbal de uma canção, geralmente de maneira sincronizada com aquela. Incluso como um formato de produção muito econômica enquanto pressupostos, o lyric vídeo se converteu em um fenômeno popular graças a sua distribuição através de Youtube e outras plataformas de vídeo online. Para lograr os objetivos propostos, realizaremos uma analises de conteúdo em uma amostra de lyric vídeos, a partir de uma metodologia baseada em propostas de diversos autores que atenda a relação do discurso audiovisual com os códigos textuais e o desenho gráfico. Os resultados que revelam nossas analises destacam a natureza gráfica e digital do formato, no qual raramente se utiliza como recurso formal a imagem fílmica gravada de forma previa a edição. De igual modo, os textos escritos apareceriam integrados no discurso de maneira extra diegético e alternaria diversas fontes tipográficas, em geral em movimento, com objetivo de lograr um auto dinamismo e assim seduzir ao expectador.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Vídeo musical; Lyric vídeo; Desenho gráfico; Analises do discurso audiovisual; Tipografia cinética; Youtube; Fandom

Received: 31/11/2017

Accepted: 17/01/2018

Correspondence: José Patricio Pérez Rufí1

patricioperez@uma.es

How to cite this article

Pérez Rufí, J. P. (2018). Lyric videos: the meeting of the music video with graphic design and the typographic composition [Lyric vídeos: el encuentro del videoclip con el diseño gráfico y la composición tipográfica] Vivat Academia. Revista de comunicación, nº 144, 01-18. doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.144.01-18. Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1071

1. INTRODUCTION

This research has as its object the study of lyric video, a subgenre within the music video that, even if born with the success of the promotional television format itself in the eighties, develops and becomes a content widely disseminated in recent years, from its consumption in the online video content platform YouTube and in its subsidiary dedicated to the video clip, Vevo. YouTube has become the priority way of distributing the video clip, even above television specialized in musical content. The recording industry, the main producer of the format with an eminently commercial or promotional purpose of music content and performers, has adapted the creation of the video clip to the new conditions of distribution and reception, in such a way that it has introduced important changes in its formal configuration. Among these adaptations of the format is the lyric video itself, as a video clip that represents, through textual codes, the entire verbal content of the song, usually synchronized with that one.

The use of text as an active resource in audiovisual discourse has been present in audiovisual productions practically from the very beginning of the cinematography (for example, the posters and placards of silent films, when no written texts have been filmed in any type of support). Television would inherit from the cinema the use of text, in a way that is even more functional, through photographic resources in the first place and, later, electronically and digitally. In the case of the video clip, the representation of the text is also a frequent resource from its very birth, although its use was punctual or was used recurrently to highlight words or lines of text of the song, when it did not create a contrast or was the counterpoint of the content of the song, or was used in a functional way (for example, to indicate the title of the song or of the interpreters).

As a by-product related to the recording industries, the karaoke videos used the representation of the text together with the absence of the vocal content of the song to invite its fans to sing these texts. Faced with this functional video model, as a guide to interpret the theme, lyric video has become a more creative format and an effective tool at the service of the promotional and commercial interests of the record industry. Called in principle to satisfy the demand of the users of contents on their favorite artists and created before by the fans, later they will be the own record industries those that are implied actively in their production. The success of the subgenre is such that, in certain cases, the lyric video of a song has reached a greater number of visualizations on YouTube than the “official” edition of the promotional video of the single. Originated in principle as products of low budget and fast production, the lyric videos are taken more and more seriously and the interest that the record industry deposits in it translates into pieces of a perfect technical finish and great creativity, leading to greater acceptance and dissemination.

The lyric video can thus be conceived as an ideal format for multiplatform distribution strategies that seek to diversify the channels of dissemination of the production of the record companies and thus expand their communication strategies with new possibilities, as part of cultural marketing plans, every time broader and more ambitious. On the creative level, the lyric video has given greater prominence to digital graphics and its multiple options, exploiting the relationship between graphic design and music video. The necessary use of typographies for the graphic representation of the written text highlights, on the other hand, the need for a study, not yet addressed, of the relationship between the written text and the audiovisual discourse.

Our research links the music video with the application of typography in audiovisual discourse, a relationship that we will study through a content analysis, taking into account the most frequent resources and their variety in a sample of lyric videos. We apply a methodology of audiovisual discourse analysis specially adapted to the study of the use of graphic / textual codes. The hypothesis that our study starts from is that the lyric videos make frequent use of a series of formal resources to the point that they come to define the nature of the format as a subgenre within the music video, resources that in turn allow its categorization.

The lyric video has barely been previously studied beyond the pages dedicated to it by Selva (2014) in his work The videoclip. Commercial communication in the music industry. We will lean, in any case, in the recent monographic studies dedicated to the videoclip made by the researchers Vernallis (2013), Rodríguez-López (2016) or Sedeño (2012), along with other references such as Viñuela (2008), Tarín Cañadas (2012) ) or O’Keeffe (2014). We also resort to the methodology for the discursive and narrative analysis of Casetti and Di Chio (1991) in the relationship between graphic and textual codes and audiovisual discourse and the compilation of contributions to the study of typesetting made by Williams (2015).

2. OBJECTIVES

Given the absence of published academic literature about the lyric video, this work presents two basic objectives as a first approach to the format:

– To analyze the format defined as lyric video in order to describe the updating of formal resources related to the presence of text, such as the relationship between the discursive diegesis and the text, the dynamism of the texts, the variety of typographic families used and the classification of said typographies. Although we do not count the frequency of updating of these resources, given the limited sample from which we started, we do take note of the formal possibilities of the format.

– In a second step, and knowing the nature of the pieces analyzed, we try to make a classification of lyric videos in different categories from the variables that have been considered within the analysis methodology.

3. NATURE AND ORIGIN OF LYRIC VIDEO

The definition complexity of the lyric video is parallel to that of the video clip itself, an increasingly strange format according to Vernallis (2013, p.181) and of such a wide versatility that it would avoid consensus regarding the features that would give unity to the set of practices (Viñuela, 2008, p.236). The concept of a video clip will depend on the perspective from which it is studied; thus, if we put the accent on the questions related to its production, we will have to understand it as a cultural product created by the record industry and linked to a commercial or promotional objective; from the point of view of discourse analysis, it would be a short-lived audiovisual format in which the band of images would be subordinated to the soundtrack, usually a musical theme, with a multitude of possibilities for production and editing and not obliged to follow a narrative development; in terms of audiovisual creation, it would be an artistic phenomenon of an audiovisual nature linked to formal experimentation and the exploration of all the possibilities that the materials that make it up allow it. We accept as valid the more general and formal meaning of Tarín Cañadas (2012, p.154), for whom the videoclip is an “audiovisual creation that builds a story, in the interrelation of music and image, which is conferred as a unique work” and that its objective is generally the promotion of other cultural contents, that is, the song. Another very complete definition is provided by Rodríguez-López (2016, p.15), for whom the music video is “an audiovisual and promotional product of the record industry that takes direct influences from the cinematographic, advertising and artistic avant-garde language”, as translation in visual codes of a song by means of impressive techniques that aim to forge “a brand image around the singer”.

The lyric video has barely received attention from the investigation in the video clip. Among the few authors who have addressed their study we can mention Selva, for whom the lyric video would be a video clip based on “the visual reproduction of the lyrics of the song” (Selva, 2014, p.347). The same author points out that the presence of the text written in the music video does not usually have excessive importance, although it also recognizes that the lyric video is “a phenomenon that seems to have gained some importance in recent years” (Selva, 2014, pp. 346-347).

The origins of it are not too clear. The previous referent (almost a proto-videoclip still) could constitute the sequence of the theme “Subterrean Homesick Blues”, within the documentary dedicated to Bob Dylan directed by DA Pennebaker Don’t look back (1967), although the sequence of posters that Dylan is showing and dropping do not collect the text of the song in its entirety, so it does not become a lyric video. This concept was later repeated by video clips such as “Mediate” by INXS (1987), “Like Dylan in the Movies” by Belle & Sebastian (1996), “Jerusalem” by Steve Earle (2002) or “ Salty Eyes” by The Matches (2006), and even by a sequence from the film Citizen Bob Roberts (Bob Roberts , Tim Robbins, 1992).

As the first antecedent of the lyric video, Selva mentions “Sign O’The Times” by Prince (1987) or “Praying for Time” by George Michael (1990) (Selva, 2014, p.348). O’Keeffe (2014) attributes the innovation to the video of the R.E.M. group “Fall On Me” (1986), although we have to mention that the representation of the text written on the screen was a very common resource in the music videos of hip hop and rap in the eighties and, especially, in the early nineties. We have to point out, in any case, that these texts did not reproduce the textual content of the entire vocal content, but several words. In this sense, the first 40 seconds of the song “I Got You Under My Skin” (1990) by Neneh Cherry, corresponding to the text sung as rap by the Swedish singer, are representative. In hip hop and rap the message of the vocal content of the subject usually has the protagonism, for that reason the videoclip respects the force of the word and represents it in writing with certain frequency.

In 2014, the thematic television channel specializing in music MTV (owned by the Viacom communication group and with franchised stations in many national markets) created the category “Best Lyric Video” in its annual MTV Video Music Awards. This fact is the consequence of the success of the format in recent years, as mentioned by Selva, and responds to the new reality of the consumption of audiovisual musical content by Internet users and MTV viewers. According to O’Keeffe (2014), the record industry’s commitment to the production of lyric videos stems from the change in the regulations for measuring the success of the singles on the US Billboard list at the beginning of 2013, given that from that moment on the number of reproductions on streaming video platforms would also be considered as indicative of the success of a music theme. This fact invited the record companies to have content created by those that exploit commercially and promotionally in portals such as YouTube, even before the production and distribution of “official” video clips.

The truth is that the phenomenon is born with the fan before it is the record companies that produce the lyric videos. At a time when not being present in the main channels of communication and distribution of content among users is equivalent to not exist mediatically, users creators identified with the figure of the fan tend to fill the gaps of “official” content of their favorites artists with their own creations. The lyric video thus becomes a phenomenon that emerged on YouTube before in Vevo, the subsidiary of Google’s video channel fruit of its agreement with the major record companies. Users demand content from musical artists on YouTube and create it when the record companies do not offer it to them; given the audiovisual nature of the platform, the users-producers will not be limited to uploading videos without images and with the sole support of the audio track, but they will create fan-videos first with fixed images of the artists (animated or not in their edition) or the covers of the discs, then with video scenes from other productions, in what some authors call UMV (User Music Video) (Sedeño, 2012, p. 1231, Milstein, 2007, p.31), and, finally, using the text of the song itself to create a format that serves to highlight the textual content. However, the democratization in the creation and distribution of content, Pérez Rufí and Gómez Pérez point out, is theoretical rather than real, given that “the classes are kept on the portal and the official channels of large companies are placed ahead of those of users “(Pérez Rufí and Gómez Pérez, 2013, p 176). In this way, the record industry ends up occupying the space created by the fan.

The flexibility of the record industry, which finally learned to use online media after the traumatic resistance to the distribution of its digital content through the Internet, led it to adopt the genre sponsored and promoted by users and to produce lyric videos and disseminate them before the publication of the official video, in case of having it, and in parallel with the edition of the single or the album. The success of these videos has led to, in several cases, the number of reproductions has been even higher than the official videos, as is the case of the pieces that have been selected for analysis in this investigation. The record industry has expanded the dissemination of its productions through the application of multiplatform strategies that increase the distribution channels of its contents and fill with content those platforms where there is a demand from users. In this way, the lyric video is promoted as an advance of later audiovisual content (the “official” video clip) and as a simultaneous production, reaching a rival in acceptance and dissemination but always benefiting the industry and the creators.

As part of this strategy of increasing the controlled production of content linked to a musical content, we can find new specialized formats of video clips such as “dance video” (music video based on the interpretation of a choreography of the promoted single, not necessarily featuring its interpreters), the “sneak peek” (or advances of several seconds of the video or the audio of the subject), the videos that serve as audiovisual support for the remixes, versions performed live or on a single stage in front of the multitude of scenarios that sometimes are shown in a video clip or editions based on new versions of the theme (for example, the video distributed on YouTube / Vevo by Shakira “ Blackmail (Salsa Version) [Official Video] ft. Maluma”). Through the multiplatform exploitation of its products, the record industry increases the diffusion within its control and limits the occupation of the spaces for its propagation that made the fan, whose contents will be increasingly of more complex access through search engines. Online video platforms, which reward and position better those contents with greater visualizations, produced and promoted by the industry.

From the point of view of creation, the lyric video can be a functional content, unlike the music video, from the moment it represents the text of the song in writing and invites attention to the vocal content of the song, to sing it or to learn the lyrics. On the other hand, it allows the application of the graphic identity linked to the production and to the interpreter, serving as a vehicle for the service of a brand, in short.

4. METHODOLOGY

The music video is an audiovisual format with many formal options that links its results to the exploitation of techniques dependent on the frequent and pronounced creativity of its creators, where functionality in the use of the image is not obligatory, while narrative is neither outlined as an objective. This variety of options and the apparent lack of application of an image grammar explain the complexity of their academic study and the frustrating attempts at categorization. From the moment we have decided to focus our attention on an accurate application of the format that is defined from the use of its formal options, our research will be articulated from the analysis of audiovisual discourse and, within it, content analysis. Quoting Rodríguez-Lópéz (2014, p 279), the music video is understood “ as a text or audiovisual subject susceptible of a detailed analysis as such and as an act of visual communication”, in such a way that the content analysis would focus “In the coding of observable properties in texts “.

We will perform a textual analysis of the format, as understood by Casetti and Di Chio (1991) in relation to the film: we will decompose the pieces present in the sample and recompose them in order to discover their construction principles and their functioning. By analyzing content, we pretend to know the most common resources in the lyric video and so identify practices that define the formal updating.

The sample we take will have to be analyzed according to a methodology consistent with the hypothesis and the objectives from which we started and will condition the conclusions we reach, as it cannot be otherwise. The extension of a research article invites to take a not very abundant sample; We believe that the analysis of ten video clips can allow us to reach conclusions appropriate to our approach. When deciding which video clip to analyze, we have tried to reduce subjective constraints and go to more or less objective references that limit the wide variety of criteria that could be considered in the election. Thus, we have made the search of the pieces through YouTube: the portal owned by Google is characterized by a wide variety of content and agreements and complicity with the recording industry have made this the most appropriate current platform for the distribution of music videos and for their location by the audience. The search for the terms “lyric video” in the portal search engine on February 20, 2017 gave rise to “u 70.200.000 results “, according to the platform. On this search we apply a filter according to the upload date, choosing “this year” (that is, during the previous twelve months), resulting in “u we 59,800,000 filtered results “, and order the results by number of views. We chose the ten with the highest number of reproductions, discarding two pieces of the results that were actually “dance videos” (a different clip mode).

The reasons for the criteria that have delimited our search have been, on the one hand, to narrow the selection to recent cases, so that our study offers results linked to the current format; on the other hand, we consider that the selection of the pieces with the highest number of reproductions is an objective criterion where the consumption preferences of YouTube users and the promotional force of the music industry are imposed. We will thus have access to a sample that reproduces the patterns of accumulated mass consumption of audiovisual content in a short time typical of musical successes and that we understand that gives rise to a representative set of pieces that we analyze.

The lyric videos analyzed are the following:

– The Chainsmokers - Closer (Lyric) ft. Halsey

– Major Lazer - Cold Water (Justin Bieber & MØ) (Official Lyric Video)

– DJ Snake ft. Justin Bieber - Let Me Love You [Lyric Video]

– Ed Sheeran - Shape Of You [Official Lyric Video]

– Enrique Iglesias - Duele el corazón (Lyric Video) ft. Wisin

– Ed Sheeran - Castle On The Hill [Official Lyric Video]

– The Chainsmokers - Paris (Lyric)

– Phia Sau M ? t Cô Gái - Soobin Hoàng S ? n (Official Lyric Video )

– The Heartbreaker - Daddy Yankee Ft Ozuna (Lyric Video)

– MC Hariel and MC Pedrinho - 4M No Touch (Lyric Video) Jorgin Deejhay

As part of the discourse analysis methodology that we apply in each video, we first take note of the nature of the image of the audiovisual piece. In this sense, we distinguish between videos with a support of filmed image, a work of complete creation through resources of digital graphics (without real image filmed, therefore), or mixing both sources of images. Frequently, the lyric videos are published in advance of the publication of singles or official videos and audiovisual recordings are not always available, being a piece edited with images and entirely digital resources.

Second, we look at the way of integrating the texts within the piece. Following the distinction of Casetti and Di Chio (1991, p.97), we identify whether the texts are diegetic or extradiegetic. The diegetic texts are those that belong to the plane of history, that is, those that have been filmed as an integrated element within the staging; the non-diegetic (or extradiegetic) texts would be those “strangers to the narrated world, although forming part of the narrator’s world”, that is, the texts that do not belong to the staging and are incorporated in the edition of the piece in a way photographic, electronic or digital.

In the third point of our analysis scheme we focus our attention on a precise question of the edition of the texts present in the discourse, the movement or not of them. We want to know if they would apply kinetic typography techniques (kinetics typography ); According to Graffica magazine (2016), kinetic typography is the text animation technique that has “the purpose of transmitting and expressing emotions through its movement it”, usually through editing programs such as Adobe After Effects. The text animation, we add, would hinder the readability of them but would create an additional impact on their own presence in the discourse, thanks to its greater focus and consequent protagonism.

Continuing with issues more related to typography, in fourth place we counted the number of fonts used in the clip to indicate if it uses only one, if two or three appear or if they are more than three. It is a common norm in the manuals for graphic designers that the number of fonts of a composition must be very small, since it could make the message more confusing (Williams, 2015). The question in this case would be to know if the artistic creativity of the video clip would justify ignoring the design questions more related to the communicative effectiveness of the compositions or not.

In fifth and last place, in line with the previous analysis of the use of fonts, we classify them to try to discover trends in this respect, even if our sample is very limited. There are many classifications of typographic families, from those of Francis Thibodeau (1921), Maximilien Vox (1954) or Aldo Navarese (1958), to associations such as the Association Typographique Internationale (1962) or the British Standards Institution (1965). We will start in our case, for its simplicity and ease in the recognition of the types, of the proposal of Robin Williams (2015) from the combination and simplification of the previous classifications. Williams distinguishes six categories: Oldstyle (serif typefaces with angled finials, moderate / fine transition finer and finer parts or diagonal accent), Modern (serif typography with thin horizontal finial, coarse / fine radical transition and vertical accent) , Slab Serif (typographies with serifs with thick horizontal finishes, with little coarse / fine transition and vertical accent), Sans Serif (typographies without serif), Script (typographies that imitate manual writing through any instrument) and Decorative (all other sources that do not follow the parameters of the previous categories).

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

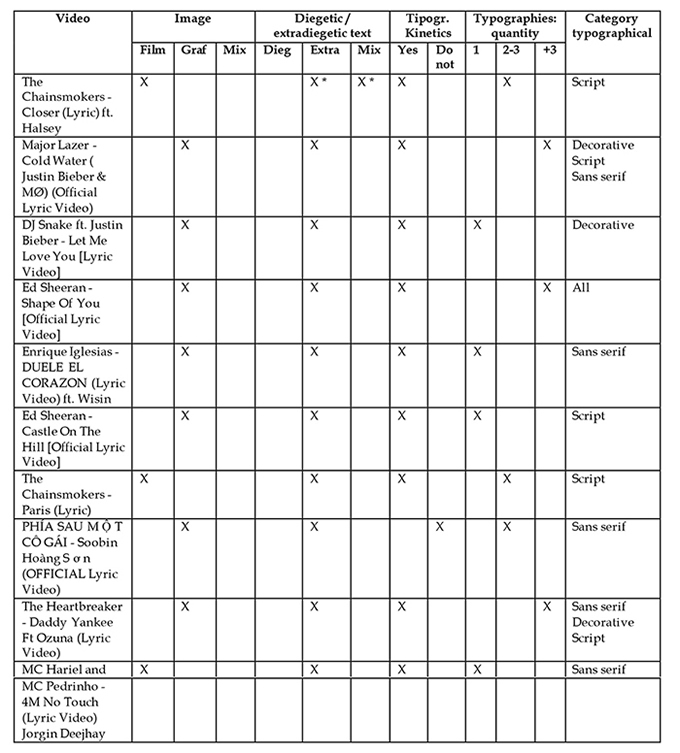

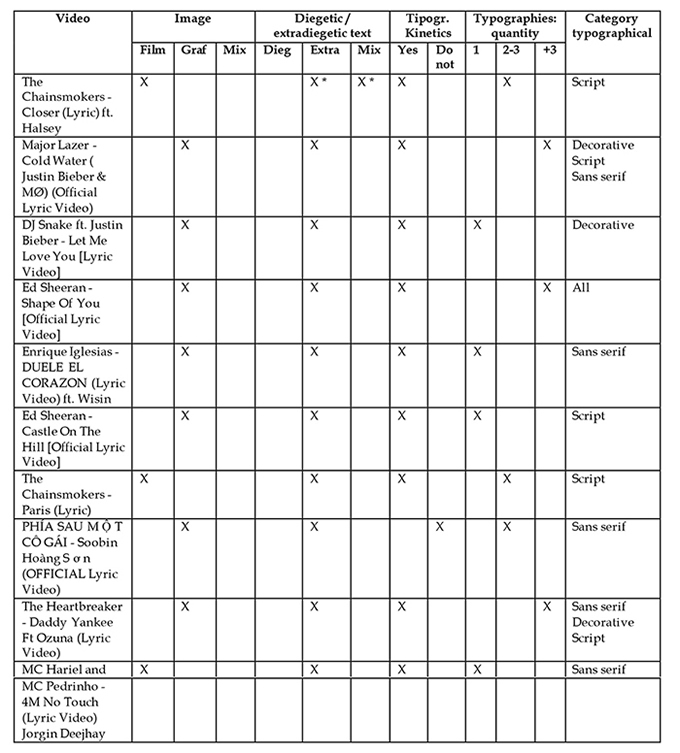

We represent first a table in which the results of the application of the chosen methodology in the sample selected for analysis are collected.

Source: Own elaboration, starting from YouTube.

Figure 1: Analysis of the selected sample of lyric videos (2016-2017).

The study of issues related to the formal aspects of the video lyric, within the content analysis allows to obtain interesting results about the construction of the video and reach conclusions that could point to a possible modeling of the format.

We will make, first of all, some comments about the sample taken for the analysis. We ignore the algorithm that allows the YouTube search engine to access the results it proposes, but it may be relevant that when introducing a time filter (videos uploaded in the last twelve months) only 15% less is obtained. results (59,800,000 videos instead of 70,200,000). To respond to the total content stored on the platform, this would mean that 85% of the videos classified as lyric videos arranged on the platform would have been distributed in the last year. This fact could well mean either that the lyric video has become a format of great presence and relevance throughout 2016, or that the cataloging and indexing of the format as lyric video has taken on greater prominence in the last year.

With respect to the ten selected videos, we see that despite the predominance of the contents created by the major multinational record companies that are imposed with the majority choice of users, there is also room for diversity, at least in the idiomatic and procedence of production: six of the videos are songs in English, two are in Spanish, one is in Brazilian Portuguese and another is in Vietnamese. Recall that these videos are the lyric videos that concentrate the greatest number of reproductions, so that the choice of the sample has prioritized the popularity and global mass consumption of certain content. As an interesting data but not determinant in terms of the purpose of our study, we note that the number of reproductions on YouTube of the sample was 1,184 million views of “Closer” to 72 million “4M No Touch”.

Entering already in the discursive analysis, we will point out in the first place that we have counted in less number of occasions lyric videos that have visual support of filmed images (only in three videos). Our purpose is not to quantify the results or reach statistical conclusions about the frequency of certain practices, but this data is significant. Thus, the most frequent practice is its generation through digital resources (digital graphics) in which it is not necessary to start a traditional audiovisual production, where it starts from the record of a scene with actors, scenarios and the rest of components of the classic cinematographic staging. We could thus say that the lyric video was born as an audiovisual format of eminently digital nature from the use of computer tools of graphic or audiovisual design, being the result of an editing work before a film production.

Of the three cases of video with filmed image that we found, two would belong to the group The Chainsmokers and are quite similar in their concept: in “Closer” we see the images of a couple in vacations on the beach and different scenarios, without interpreting the musical theme, and in “Paris” it is a girl who walks along the beach, without major narrative elements or interpretation of the song. In the third of the videos, the young singers of the song interpret the song looking at the camera and dancing on a neutral stage, as a purely “performative” clip.

Although it is not our objective to make a critical assessment of the contents, we note that the quality of these audiovisual productions filmed is not too much, beyond the technical care in filming and editing. The production seems to be very economical, without great means or a creative or formal development that distances them from more mediocre budget clips.

As for the lyric videos generated through digital graphics, we notice a wide variety of possibilities, ranging from the most creative animation pieces for the two singles by Ed Sheeran to the more conventional clips by Enrique Iglesias or Phía Sau M?t Cô Gái , practically karaoke videos with lyrics of the song about the interpreter’s photographs. The most elaborated videos thus become almost animated shorts in which the text has a priority focus. Understood in this way, the format lends itself more effectively to trying to transmit the tone and values associated to both the song and the identity created for the performer or for a specific musical project. The videos generated by digital graphics create their own diegesis of possible worlds or of articulation of formal resources with absolute independence of the real referents, which allows a great variety of possibilities at the service of the artistic wills of the creators.

The next aspect of the analysis deals with the presence of texts in a diegetic or extradiegetic way. There is unanimity in the sample: all the texts would be extradiegetic, that is, not pertaining to the staging or the filmed image being added (digitally) through editing programs. Although this is not the case here, videos can be located where the texts have been integrated into the scenario and the changes of frames or plane have explored and “read” said texts.

The reason why the texts are extradiegetic can be due to a mere question of production and economy of the media: the integration of the texts in the filmed image would require a very precise planning and in many cases practically a detailed articulation as a choreography of all the components of the staging. However, the editing of the texts in the post-production phase allows for less dependence on previous filming. Lyric videos very neat as the one of Ed Sheeran “Shape of You” would require of the same precise and choreographic planning of the videos filmed with diegetic texts, although they would always form part of the process of postproduction, with the flexibility that the editing programs allow. video and digital postproduction.

Let us note, within the sample taken, as the only exception the presence of two planes with diegetic texts in the video of The Chainsmokers “Closer”, where the name of the performers and the song appear written at the foot of some photographs taken with Polaroid. The rest of the clip incorporates the texts in an extradiegetic way, which is why we have classified the way of incorporating the texts in that category.

With respect to the kinetics of typographies, we observe that practically all of the lyric videos in the sample (with the exception of the video of the Vietnamese interpreter) edit the (extradiegetic) texts in movement. In this way, an additional impact is obtained on them, gaining in focus and protagonism, while imprinting on the format an effect of rhythm and dynamism, of speed. The creation of an impression of rhythm is not achieved, therefore, only through an accelerated edition of planes of short duration in its temporal development, but also with the movement of the texts within each plane or within the frames.

As a consequence, the texts hinder their readability. This fact will define a basic feature of the nature of the video lyric: in front of the functionality of the karaoke video, in which the appearance of the texts is subordinated to the optimization of the reading in the best conditions, the lyric video plays with the texts as a resource artistic (even aesthetic) before functional, a reason why a better readability is not the objective to achieve.

The number of typographic families present in each of the videos analyzed is a matter more related to typographic composition and graphic design than the analysis of audiovisual discourse. However, when dealing with the text of the preferred resource of the lyric video, we consider that its inclusion in this study allows us to reach conclusions about the nature and use of the audiovisual language of the analyzed format.

In this section we observe that the number of families applied in the texts of each video does not follow common trends and all kinds of options are used. Thus, only one typeface is used in four pieces of the selected sample. The manuals for graphic designers usually recommend, as we have pointed out, the simplification of the amount of graphic and typographic resources (Williams, 2015), which would lead to the reduction of the number of fonts in the composition of a still image. In this way, the complexity of the composition would be reduced, the creation of meanings that would result from the typographic mixture and the values of each of the typefaces would be limited and the emphasis would be placed on the functionality of the composition and the optimization of the legibility of the texts.

In the case of the lyric video with a single typographic family, attention is detracted from the source (understood as a graphic element, as it is a figure on a background) to try to shift the reader’s interest towards other elements of the audiovisual piece: content of the texts, their composition, other types of resources, the content of the staging, the sound component, etc. The four videos that apply a single typographic family to their texts are very different in the rest of the content and resources present (including here the animation pieces with texts by Dj Snake, Justin Bieber or Ed Sheeran in “Castle On The Hill”, as well like the simpler video of MC Hariel and MC Pedrinho or the practically karaoke clip of Enrique Iglesias), which does not allow us to reach conclusions that unify the meaning of the use of a single typography beyond the stated reasons.

Three will be the lyric videos of the sample that apply two or three typographic families and three others that present more than three families. The objective of the typographical variety would be linked to the artistic intentions and dynamism of the format: regardless of the functionality imposed by the limitation of families, the lyric video aims to maintain attention by making use of all the resources available, including both the kinetic typography as the diversity of fonts, styles, colors, etc. Let us draw attention to the particular use that is made of the number of families in the lyric video of The Chainsmokers “Closer”; in this case the texts would be represented with two different typographic families, one for the text sung on the sound track by the male performer and one for the text sung by the female performer. In this way, a functional use of typographic choice is made.

About the most frequent categories in the sample taken, the script types stand out above all, that is, those fonts that simulate having been written by hand. Script fonts appear in six of the ten videos analyzed. We could interpret that their use responds to the need to transmit the values associated with its apparent human nature: here the interpreter seems to write the texts with his own hand, transmitting an impression of more human and close content, compared to the coldness and normalization of the texts. Fonts created “through the machine”.

In the case of the “Closer” texts of The Chainsmokers this identification between handwritten typography and interpreters is reinforced from the moment when the typefacs are two, depending on whether the sung text is interpreted by the male singer or the female singer of the theme. The texts of “Castle On The Hill” by Ed Sheeran also seem to respond to this singer-songwriter’s desire to narrate his own life experiences, from the moment the song simulates a biographical account of different stages of his life.

The use of the script category could thus be linked to the desire to personalize not only the texts, but also the musical theme and the video clip. Another interpretation could be inferred from this majority use of script fonts: the second decade of the 21st century has seen the use of scripts to become a fashionable phenomenon. If previously the graphic design manuals did not recommend their use due to the difficulty of readability they could present and the informality they connoted, even infantilism (Williams, 2015), in recent years they became a habitual resource in compositions linked to an aesthetic modern and in principle minority: the hipster aesthetic was linked to nostalgia, to the taste for retro and vintage, as could be perceived from the claim of the old materials, the worn industrial and handmade products, the tile floors of hydraulic tiles , the use of blackboard and chalk as a support for informative and advertising messages, the interest in the recovery of analogue technology from an aesthetic before a functional level and everything that was synonymous with craftsmanship or handmade. The script typographies lent themselves to this nostalgic use of formats and creation techniques surpassed from afar by the digitalization of the means of production, and they became the fashion text, first in more minority and exclusive social contexts and later more massive, industrial and commercial ones. Script fonts are in vogue and lyric videos have been subordinated to fashion trends in typographic and visual composition, in short.

In five of the videos analyzed, we will find sans serif typefaces, texts that have not finishing touches and austere, neutral, cold and tremendously functional. The sans serif types are, simultaneously, so devoid of connotative elements that they expand their ideological universe, enhancing the values of the rest of the resources and contents of the composition. The neutrality of the sans serif turns them into “sponges” that are impregnated with the message conveyed by the content of the song, by the identity of the artist or by the other resources present in the speech. The videos of Phía Sau M?t Cô Gái or Enrique Iglesias are tremendously functional in this sense and try to eliminate almost all the emotion in the use of the texts. In the case of the lyric video of Enrique Iglesias, this emotion or the connotation transmitted by the text will not come from the typographic category, but from the mixture of sizes in the fonts, their composition, alignments and even color, highlighting in this way some words above others. The clip by MC Hariel and MC Pedrinho does not intend to draw attention to the figure of the text, but to the interpreters themselves and the content of their message, even if the typography is kinetic and acquires great dynamism in its mode of appearance and in the general typographic composition. The use of typographical categories refers to the one we mentioned as typical of rap and hip hop video clips of the nineties.

The creativity and the application of an infinity of audiovisual resources accepted for the video clip would explain the use of the fonts called decorative by Williams. These, more difficult to catalog, respond to the connotations of those who want to print the written text and at the whim of the creators in their visual composition. They will appear in five of the videos analyzed, in most cases combined with other categories (such as sans serif or script). As a paradigmatic case, the lyric video of “Shape of You” by Ed Sheeran presents a piece of graphic animation in which the creative possibilities of the text as a visual resource are exploited to the maximum, incorporating a multitude of fonts (of all categories), the variety of colors, shapes, arrangement within the frame, etc. This achieves an enormous dynamism and a result that is not very functional in terms of the legibility of the text, but attractive, unique and with a vocation to search of the artistic value and to activate strategies of visual seduction.

From the analysis of the speech made about the selected lyric videos, we dare to model the possibilities that the format allows and to establish three categories in this way:

1. Lyric video based on filming or scene photography, in which texts can appear in a diegetic or extradiegetic way, with movement or not. In this type of videos, the number of typographic sources is usually limited and the focus of the content of the staging is shared with the text itself with the lyrics of the song.

2. Lyric video completely edited digitally, without the presence of a real staging that has been filmed or photographed. Based on post-production editing techniques, it usually focuses on the texts themselves rather than on other contents, which invites us to explore and exploit all the formal and discursive possibilities that digital publishing allows, thus giving priority to the artistic over the functional.

3. Functional Lyric video. Closer to the traditional karaoke video, it subordinates the application of effects of realization or post-production to the representation of the textual content of the song in the most efficient and clear way possible. The objective will be the optimization of the readability of the texts, which will lead to static texts or with very limited effects of movement and the reduction of the diversity of typographical sources to one or two families that allow a good readability.

4. The lyric mixed video. Given the wide combination of possibilities that both the video clip in general and the lyric video in particular allows, we believe it is convenient to resort to a broader and less precise category where all the practices that do not identify with the aforementioned categories can be accommodated. The discursive possibilities of lyric video are many and only limited by the constants that define its nature as an audiovisual product at the service of a musical theme in which the texts that make up the vocal content of the song are represented graphically. The mixed lyric video could also result from the combination of the previous categorized models.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The relative novelty of lyric video as a phenomenon of high demand and broad recent consumption and the absence of an academic literature that has previously addressed its research highlight the need for consideration of the format within the investigation of the video clip. The relative low cost of production that it frequently requires and the possibility of obtaining a mass distribution and consumption through online video platforms such as YouTube makes it an effective format within the communication strategies of the recording industries. If we also consider that the sum of reproductions of a musical product in any format, medium and device contributes to give greater visibility to it and increases its notoriety (as evidenced by the rules that make up the Billboard chart), we must conclude that it is a highly functional instrument to the commercial objectives of the industry.

Considered still as a format prior to the “official” video around a musical theme, if not complementary, we must point out that it can become a substitute format of the previous one, to the point that it can surpass the “official” video in terms of number of reproductions on YouTube, asthe case of The Chainsmokers low-budget lyric-videos.

As a subsidiary format of the conventional videoclip, the lyric video shares with the music video its formal complexity, justified from its artistic and experimental nature and in the need to keep the viewer’s attention and impact or seduce him. In parallel, it shares with the video clip the disparity of formal possibilities that it can update and the consequent difficulty of its analysis and categorization.

In any case, the need forced by the very definition of the nature of the format of representing written texts will provide resources that can be analyzed and, therefore, to apply a methodology with categories before which they will have to position themselves in a sense another each of the lyric videos, but that will end up configuring common and even frequent practices. In this sense, we have verified that the lyric video has linked, as other types of video clips did, the fundamentals of graphic design with audiovisual discourse, since the use of typographies implies the necessary graphic support to be represented in writing. texts.

The main conclusion reached by our analysis is that the conception of lyric video will involve two different options linked to the functionality of the composition and the application of graphic or textual resources: thus, we find pieces in which the main objective is to transmit the textual message in the most effective way, which explains more neutral, functional and orderly compositions, typical of the Swiss Design functionalism, compared to another lyric video model in which the objective is not the most effective communication of the text message, but the application of creative and artistic techniques in which the text is a graphic resource, where the optimization of its readability will not prevail . As in the video clip, the formal options are as many as the creators want to apply and their study options open as many research channels as those opened by the music video itself.

REFERENCES

1. Casetti F, Di-Chio F (1991). Cómo analizar un film. Barcelona: Paidós.

2. Graffica (2016). ¿Qué es la tipografía cinética?, Graffica. Recuperado de http://graffica.info/que-es-la-tipografia-cinetica

3. Milstein (2007). Case Study: Anime Music Videos, En Sexton J (Ed.). Music, Sound and Multimedia: From the Live to the Virtual. Edimburg: Edimburg University Press.

4. O’Keeffe (2014). Where Did All These Videos Come From, and Why Are We Giving Them Awards?, The Atlantic. Recuperado de: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/08/where-did-all-these-lyric-videos-come-from-and-why-are-we-giving-them-awards/376084/

5. Pérez-Rufí JP, Gómez-Pérez FJ (2013). Nuevos formatos audiovisuales en Internet: cuando el usuario es quien innova, en De-Salas-Nestares MI, Mira-Pastor E, (coord.). Prospectivas y tendencias para la comunicación en el siglo XXI. Madrid: CEU Ediciones.

6. Rodríguez-López J (2014). Diseño de un modelo crítico-estilístico para el análisis de la producción videográfica musical de Andy Warhol como industria cultural. (Tesis inédita de doctorado). Universidad de Huelva, Huelva.

7. Rodríguez-López J (2016). Andy Warhol y el vídeo musical. Huelva: Pábilo Editorial.

8. Sedeño A (2012). Producción social de videoclips. Fenómeno fandom y vídeo musical en crisis. Comunicación: revista Internacional de Comunicación Audiovisual, Publicidad y Estudios Culturales, 10, 1224-1235. Recuperado de https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3992540&orden=354871&info=link

9. Selva-Ruiz D (2014). El videoclip. Comunicación comercial en la industria musical. Sevilla: Ediciones Alfar.

10. Tarín-Cañadas M (2012). La narrativa en el videoclip Knives Out, de Michel Gondry. Icono 14, 10(2):148-167. Recuperado de http://www.icono14.net/ojs/index.php/icono14/article/view/482/365

11. Vernallis C (2013). Unruly Media. YouTube, Music Video, and the New Digital Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

12. Viñuela-Suárez E (2008). La autoría en el vídeo musical: signo de identidad y estrategia comercial. Revista Garoza, 8, 235-247. Recuperado de http://webs.ono.com/garoza/G8-Vinuela.pdf

13. Williams R (2015). Diseño gráfico: principios y tipografía. Madrid: Anaya Multimedia.

AUTHOR

José Patricio Pérez Rufí

Professor of the Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising of the Faculty of Communication Sciences of the University of Málaga. He holds a PhD in Audiovisual Communication from the University of Seville (2005), a degree in Audiovisual Communication (1999) and a degree in Journalism (1997) from the University of Seville. He is a member of the Communicav research team. He has published several monographs in editorials such as T & B, Síntesis, Quiasmo, Gerüst Creaciones, Tutorial Formación and Eumed.net. He has participated in collective books edited by T & B, Dolmen, Forge, Ministry of Culture and ICAA, Padilla or Oedipus, among others. He has published in numerous research journals specialized in Communication.

https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=Qf8yHP0AAAAJ