10.15178/va.2018.143.111-134

RESEARCH

MEDIA COVERAGE OF PODEMOS POLITICAL PARTY IN EL PAÍS AND PÚBLICO: AN ANALYSIS FROM THE FRAMING THEORY

EL TRATAMIENTO PERIODÍSTICO DEL PARTIDO POLÍTICO PODEMOS EN EL PAÍS Y PÚBLICO: UN ANÁLISIS DESDE LA TEORÍA DEL FRAMING

O TRATAMENTO JORNALISTICO DO PARTIDO POLITICO DE PODEMOS NO EL PAIS E PÚBLICO: UMA ANALISES DESDE A TEORIA DE FRAMING

Manuel Peris-Vidal1 Doctor from the Pablo de Olavide University in Seville, Spain

1Pablo de Olavide University of Seville, Spain

ABSTRACT

The irruption of Podemos in the Spanish political scene in 2014 was a great revolution in the traditional party system, since this formation received a large part of the vote of the citizens, unhappy with the budget cuts and with the extension of political corruption during the last decade. Because Podemos has become a threat to PP and PSOE, criticism from some media to this party has been increasing. However, there has also been unconditional support for that party from other media. As a consequence, we believe it necessary to carry out, from the theory of framing, and through content analysis, an examination of the approach given by the newspapers El País and Público to the news about Podemos in November 2016. We found relevant the analysis of the journalistic treatment of certain aspects that characterize the discourse of the general secretary of formation, Pablo Iglesias, as the identification of Podemos with the people or the systematic disqualification of anyone who is critical of his party.

KEYWORDS: Framing theory; Podemos; Media; Opinion-building; Framing; Responsibility; Content analysis

RESUMEN

La irrupción de Podemos en el panorama político español en el año 2014 supuso una gran revolución en el sistema tradicional de partidos, puesto que esta formación recogió gran parte del voto de la ciudadanía descontenta con los recortes presupuestarios y con la extensión de la corrupción política durante la última década. Debido a que Podemos se ha convertido en una amenaza para PP y PSOE, las críticas de algunos medios de comunicación hacia este partido han ido en aumento. Sin embargo, también se ha producido el apoyo incondicional a dicho partido por parte de otros medios. Como consecuencia, hemos creído necesario llevar a cabo, desde la teoría del framing, y a través del análisis de contenido, un examen del enfoque dado por los diarios El País y Público a las noticias sobre Podemos en noviembre de 2016. Nos ha parecido relevante el análisis del tratamiento periodístico de ciertos aspectos que caracterizan el discurso del secretario general de la formación, Pablo Iglesias, como la identificación de Podemos con el pueblo o la descalificación sistemática de todo aquel que se muestre crítico con su partido.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Teoría del framing; Podemos; Medios de comunicación; Opinion-building; Encuadre; Responsabilidad; Análisis de contenido

RESUME

A irrupção de Podemos no panorama político espanhol no ano de 2014 supões uma grande revolução no sistema tradicional de partidos, posto que esta formação percorreu grande parte do voto da cidadania descontente com os recortes orçamentários e com a extensão da corrupção política durante a última década. Devido a que o partido Podemos se converteu em uma ameaça para o Partido Popular e para o partido Socialista, as críticas de alguns meios de comunicação foram em aumento. Porém, também se produziu o apoio incondicional a este partido por parte de outros meios. Como consequência creiamos necessário levar a cabo, desde a teoria de framing, e através da analises de conteúdo, um exame do enfoque dados pelos Jornais El País e Público das notícias sobre Podemos em novembro de 2016. Nos pareceu relevante a analises do tratamento jornalístico de certos aspectos que caracterizam o discurso do secretário geral do partido, Pablo Iglesias, com a identificação de Podemos com a população ou a desqualificação sistemática de todo aquele que se mostra critico com seu partido.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Teoria de Framing; Podemos; Meios de comunicação; Opinion Building; Enquadre; Responsabilidade; Analises de conteúdo

Received: 10/02/2018

Accepted: 27/04/2018

Correspondence: Manuel Peris Vida

mperisvidal@hotmail.com

Cómo citar el artículo

Peris Vidal, M. (2018). Media coverage of Podemos political party in El País and Público: an analysis from the framing theory. [El tratamiento periodístico del partido político Podemos en El País y Público: un análisis desde la teoría del framing].

Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 143, 111-134

doi: http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2018.143.111-134

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1072

1. INTRODUCTION

The fact that the political party Podemos, which emerged in January 2014, became the third political force in Spain after the general elections of 2015, was an important element of destabilization of the traditional bipartisanship of the Partido Pular (PP) and the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE). The political marketing strategy of this formation was based, to a great extent, on the focus on its leader, Pablo Iglesias and, as pointed out by Capilla (2014, p.26), the success of the irruption of Podemos was based on the television charisma of Iglesias. An example of this is the placement of the image of its leader on the Podemos candidacy ticket for the May 2014 European elections (Gallardo-Camacho and Lavín, 2016, p 274). However, there is a specific aspect of the Podemos strategy in terms of the leader’s presentation, which differentiates it from the populist style: instead of betting on the individual charisma capable of dragging the masses: it always appears nuanced by the group support (Arroyas and Pérez Díaz, 2016, page 61). The latter implies, therefore, that the discourse of iglesiasIglesias always appears nuanced by the support of the group. In any case, in this work we are especially interested in the approach given to one of the characteristics of Podemos’ discourse: the antithesis between the them and the we and the demonization of the adversary. In this way, we have set out to analyze whether the analyzed media adopt a critical approach or limit themselves to reproducing the discourse of this political formation without questioning it.

2. OBJECTIVES

The central hypothesis of the present study is that the media coverage of the political activity of Podemos by El País and Público is framed from very different angles, in such a way that the persuasive force of the discourse of this political party is mitigated or increased to a greater or lesser extent. . The latter has important consequences in the process of forming public opinion (opinion-building), through the elaboration of general frameworks for the interpretation of the aforementioned facts.

In this sense, we attach great importance to the role of the media in the opinion-building process, because we share the conclusions of Giorgio Grossi on this matter. This author concludes, by following the research perspective of Lang and Lang (1983) on public opinion, that the media have progressively broadened their role within the public sphere, and have become, not only as responsible of the agenda of the topics to be discussed, but also of the opinions on such topics (2007, p.104). In this way, the media take a leading role in the process of forming public opinion, acting not only as communication channels, but also as autonomous producers of public discourses.

From the above, in this work the following objectives have been established:

– Check which have been the generic frameworks of the Semetko and Valkenburg typology most frequently used in the newspapers El País and Público in the information about Podemos.

– Analyze the ideas associated with these generic frames and the possible framing strategies related to the transmission of said ideas.

– Verify whether a critical or favorable perspective is adopted towards the discourse of Podemos in the preparation of news about this formation.

3. METHODOLOGY

The research technique that has been used in this study is content analysis, from the framing or frame theory approach. In relation to this theoretical perspective, it should be emphasized that, in the field of communication sciences, the theory of framing has been used in a growing number of studies, and currently occupies a prominent place in research developed in that field.

The theory of framing, by claiming that news is perceptions of reality, is rejecting the objectivist current that dominated academic research and journalistic practice during the 1960s and 1970s (Berganza, 2003, p.10). This current, which argued that “the facts are sacred, but opinions are free,” advocated the radical separation between information and opinion (idem). Faced with what is defended from this perspective, María Teresa Sádaba describes the process of definition and construction of the contents offered by the mass media, from the perspective of the framing theory: “the answer offered by the theory of framing to objectivism is to deny its postulates, since it argues that, when it tells what is happening, the journalist frames the reality and contributes his point of view “(2001, p.159). It is being described, in this way, in which way the journalist organizes the reality on which he / she informs, based on certain schemes or categories.

The theoretical foundations that allowed the development of framing theory, according to Alberto Ardèvol-Abreu (2015, p.428), lie in interpretive sociology, which considers that the interpretation that individuals make of reality depends fundamentally on the interaction and of the definition of situations. However, the idea of the frame was used for the first time in a sense similar to the current one by Gregory Bateson in the field of cognitive psychology, through the essay entitled A Theory of Play and Fantasy (1955 [1972]). Bateson showed, according to Deborah Tannen (1993, p.3), that no communicative action, verbal or non-verbal, can be understood without reference to the metacommunicative message about what is happening, that is, without taking into account everything that the interpretation framework provides to these actions. The frame, therefore, like the frame of a painting, tries to organize the perception of the subject, encouraging people to pay attention to what is inside and to ignore what is outside the frame, thus facilitating the understanding of the messages contained in the frame (Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015, pp. 428-429). Although the theoretical body of framing was developed since the 1970s, initially by the hand of cognitive psychology, these theories will be recovered for sociology by Erving Goffman (1974), and it will be this perspective that will be used in communication studies, expanding, in this way, the original meaning of the frame from the individual to the collective, because for Goffman the frames are instruments of society that allow maintaining a shared interpretation of reality (Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015 , p 429).

Framing, according to Robert Entman (1993, p.52), involves selecting some aspects of reality and granting them more relevance in a communicative text, so as to promote a certain definition of the problem, a causal interpretation, a moral evaluation and / or a treatment recommendation for the subject described. The effects of this process of frame or framing, according to Maxwell McCombs, Donald Shaw and David Weaver (1997), are not only related to the agenda-setting, but the framing is in fact an extension of the agenda- setting (Scheufele, 1999, p.103). In fact, McCombs argues that framing can be redefined in terms of establishing a second-level agenda: “framing is the selection of -and the emphasis on- concrete attributes in the media agenda when we speak of an object” (2006, p. 170). This author, therefore, links the agenda-setting theory with the concept of framing through the establishment of the attributes agenda.

However, there have been many critical voices with this vision of framing because it generates an important confusion in the definition of differentiated concepts such as priming, agenda-setting or framing (Kim et al ., 2002, Price et al., 1997). In this sense, Scheufele (1999, p.104) has defended the need to differentiate framing from other closely related concepts in research on the effects of the media. In fact, in the definition of Entman (1993, p.54), this concept is clearly differentiated from the agenda-setting theory, since it focuses on the selection of topics or topics that are covered by the media and the perception of its importance, while the framing determines how people understand and remember a particular problem, and how they evaluate it and decide to act on it.

Beyond the arguments expressed from positions as different as those we have just mentioned, there is currently a majority among researchers in communication who consider that the theories of framing and agenda-setting are complementary but autonomous (Ardèvol-Abreu , 2015, p 427). According to Yuqiong Zhou and Patricia Moy (2007, p.81), these two theories differ, precisely, in the concrete aspect of the media that constitutes the center of their research: while the agenda-setting theory focuses on the study of the relevance of the themes; the main object of the framing theory is the relevance of the frames.

The newspapers chosen for the analysis were El País and Público, given that we have understood that these media have a very different vision of the role that the leftist forces must play in the governance of the Spanish State.

The time interval selected was November 2016, due to the fact that during this period the political formation Podemos and some of its leaders were affected by various controversies, and we considered it important to analyze the different framing strategies carried out from the newspapers examined on these issues.

The selected sample is composed of all the journalistic texts belonging to the different informative genres published in these journals during the month of November 2016, which have been prepared by journalists from El País or Público and whose main theme has been, in addition, the Podemos party. Specifically, all the news, reports and interviews that have been published during this period have been analyzed.

In the case of the Público newspaper, a total of 49 registration units have been examined, while 47 informative texts of El País have been analyzed.

On the one hand, through a deductive approach, the generic frames present in the two newspapers analyzed have been quantified, taking as a reference the typology of frames that Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) developed from the frames that had been identified in previous studies. The five mentioned frames are the following ones (2000, pp. 95-96):

– Frame of conflict emphasizes the conflict between individuals, groups or institutions as a means of attracting the interest of the audience.

– Frame of human interest: it brings the human side or an emotional angle to the presentation of an event, issue or problem.

– Frame of economic consequences: reports on an event, problem or issue in terms of the economic consequences that it will have on a person, group, institution, region or country.

– Frame of morality: situates the event, the problem or the topic in the context of religious principles or moral prescriptions.

– Frame of responsibility: presents a topic or a problem in such a way that it attributes responsibility for its origin or its solution, either to the Government, or to a person or a group.

These authors developed a scale composed of 20 variables using an average of the scores of each individual element in each of these variables

The functions that, according to Entman (1993, p.52), can play as a frame have also been taken into account. Based on the aforementioned typologies, the units of the sample have been examined in order to discover the different ways of approaching the reality of these journals and which are their main focuses of interest. From all this, we have been able to identify the ideas that structure the general frames that predominate in the discourse of each of the media analyzed in relation to the current situation of Podemos and its leader.

On the other hand, from an inductive approach, the main thematic frameworks have been identified from the ideas linked to the aforementioned generic frames

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. The Público newspaper. A benevolent approach on Podemos

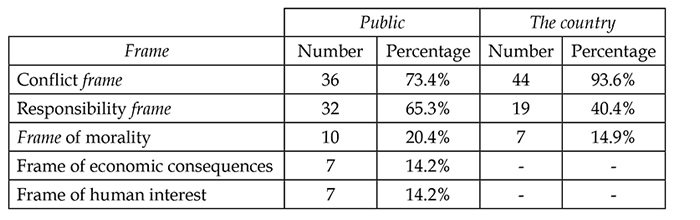

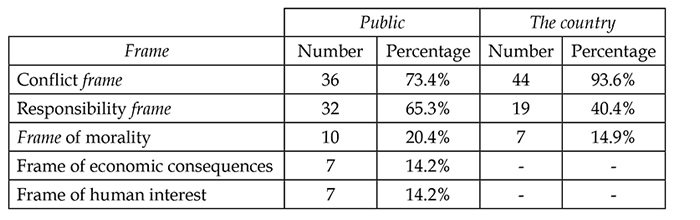

If we consider the type of frames Semetko and Valkenburg, the most widespread news frame in the Público daily and s the conflict, which is present in 36 of the units analyzed, representing 73.4% of the corpus examined.

This frame is linked, in a large number of informations, to the idea that Podemos represents an ideological option and a way of understanding politics radically opposed to those of the traditional parties, and that it is opposed to the business and political elites. This idea of the opposition between traditional politics and the new politics, supposedly represented by Podemos, is present in 36.7% of the units analyzed. On a few occasions, the organizational characteristics that differentiate this party from the two major traditional parties of the Spanish State -PP and PSOE- are underscored, such as the financing of Podemos through the contributions of its supporters (Público.es, 14/11 / 2016). In fact, in the headline of the news it is indicated that this party has already returned the loans with which they financed their electoral campaign. Other times, the accomplice behavior of the traditional moderate parties is highlighted, criticized by the representatives of Podemos. These parties supposedly prevented in 1977, , that the Spanish citizenship decided whether they preferred the monarchy or the republic as a form of State (Público.es , 11/19/2016). The statements of Pablo Iglesias on the complicity between the political and business elites are also reproduced, which is reflected in the position of the former ministers and former presidents of the Government who are part of some boards of directors of large companies (Plaza, Público.es , 19 / 11/2016; López de Miguel, Público.es , 11/23/2016).

On the other hand, in a significant number of news the politically incorrect behavior of the leaders of Podemos is highlighted, which distinguishes them from the usual conduct of the majority parties. An example of this is the resignation of the deputies of Unidos Podemos to attend the parade and other ceremonial acts related to the Solemn Opening of the XII Legislature, which is underlined in a Público headline on November 17, through the following words, pronounced by Iglesias: “’Patriotism is defending civil rights’, not going to ‘hand kissing and parades’” (Araque, Público.es, 11/17/2016).

Finally, it should be noted that the identification of Podemos with “the people” in front of the power of the elites, is also an idea that usually appears in this newspaper and that is related to the framing of conflict. The actions of this party are highlighted in defense of the most vulnerable workers, such as employees in the telemarketing sector (Vargas, Publico.es, 11/16/2016, López de Miguel, Público.es, 11/28/2016), or we can identify Podemos with the working class, as when it is affirmed that the road map of Iglesias goes through “recovering the concept of the class struggle” (López de Miguel, Público.es , 11/24/2016). All the aspects that we have commented so far on the approach of Público are related to the narrative of the speech of Pablo Iglesias to which Arroyas and Pérez Díaz refer (2016, page 61), whose driving force is the confrontation between the them and the us, between the corrupt caste and Podemos as the agglutinator of popular support. This newspaper, consequently, is limited, in numerous occasions, to reproduce in an uncritical way the narrative of the speech of the leader of Podemos.

The frame of conflict is also related to the idea that Podemos represents the real political opposition to the Popular Party, and that the real ideological conflict in Spanish politics occurs between the PP and Podemos. This message is present in 18.4% of the corpus examined, and in Público it is usually transmitted, on the one hand, through the idea that Podemos is the party that most annoys the PP Government (like the news in which the following sentence is included: “With this phrase Pablo Casado acknowledged this Wednesday that the PP did not want Podemos facing them” (Público.es, 02/11/2016 [a ]). On the other hand, it is also reflected in the speech that Podemos is the most combative party with the Popular Party, examples of the latter are the emphasis placed on the confrontation of Iglesias with the minister Álvaro Nadal in the information line: “The leader of Podemos leads a tense dialectical confrontation with the holder of Energy “(López de Miguel, Público.es, 11/23/2016), or the emphasis placed on the work carried out by the leaders of Unidos Podemos to get the former Minister of the Interior, Jorge Fernández Díaz, not to be appointed president of the Committee on Foreign Affairs in Congress (in one of the reports, in fact, underlines the PSOE’s attempt to take credit for this veto action, with these words: “The PSOE now arrogates the veto to Fernández Díaz “( Público.es , 11/16/2016).

Another issue of less relevance linked to the framing of conflict in Público is the internal confrontation that took place in Podemos to lead the party in the Community of Madrid, and the differences between the sectors led by Pablo Iglesias and Íñigo Errejón at the state level. Specifically, this issue appears on 7 occasions, representing 14.3% of the total analyzed. This conflict is described as a mere confrontation of ideas within a democratic party. One example is the approach to information about the primary elections of Podemos Andalucía, where the common elements defended by the three candidates for the General Secretariat are underlined, and the existing unity is summarized in its main political proposals: “There are more differences between the candidates in the party’s organizational model and the role they should play in relation to the PSOE than in the political action “(Cela, Público.es, 04/11/2016).

Another relevant framing in the Público newspaper is that of responsibility, which appears in 32 units (which represent 65.3% of the sample), as shown in table 1. This frame is related, in a large number of occasions, with the following thematic framework: the existence of a supposed media and political conspiracy against Podemos. In fact, in 30% of the news of the analyzed sample the frame of responsibility has to do with the presence of the message that this political formation is the victim of a campaign undertaken by certain media and political groups. From the information in this newspaper it is easy to reach the conclusion that these groups are at the origin, supposedly, of many of the polemics that affect Podemos. The most obvious example of the latter is the treatment given in Público to the criticisms leveled at the senator of Podemos Ramón Espinar for having benefited from the sale of a public protection home in 2011. Specifically, in the news item of 2 November 2016 the accusations of Iglesias against the PRISA Group and its president, Juan Luis Cebrián, for attempting to intervene in the primary elections, both of Podemos, and of the PSOE. The idea is summarized in the following sentence of iglesias obtained from the social network Twitter: “Cebrián devices storming our primaries, as in the PSOE. Here we vote in freedom”(Público.es, 11/02/2016 [ b ]). It should also be noted that the headline of the news includes a phrase almost identical to the one just mentioned.

Also, a day later a great prominence is given to the interpretation of Pablo Iglesias on the information referring to Espinar, so that the headline of the news already perfectly summarizes the vision of the leader of Podemos: “Pablo Iglesias denounces that the controversy of Espinar is an attack on him to weaken his leadership”( Público.es , 11/03/2016). The body of the news also highlights the statements of Iglesias in which it states that the interest in weakening its leadership does not come only from the PRISA Group, but there are other “power groups” that pursue the same goal (idem) . But this information not only reflects this interpretation of the existence of a supposed campaign against Podemos, but also underlines another conjecture elaborated by Iglesias about the reason for the criticisms made by the former IU federal coordinator, Cayo Lara, to the performance Espinar: “the leader of Podemos has blamed the words of Lara to ‘rancor’” (idem). It is therefore linking the behavior of Lara with the state of mind of the latter after the defeat of his thesis against those of Alberto Garzón.

This news does not mention any alternative explanation to those of Iglesias about the causes of the controversy over Espinar, which contrasts with the vision transmitted by El País in a story published on the same day. In it opinions different from those of the leader of Podemos are gathered, coming from other sectors of said political formation, such as those of José Manuel López or Jorge Lago, next to the so-called Errejón sector (García de Blas, Elpais.com , 03/11 / 2016 [a]). Likewise, El País questions the vision of Iglesias for pointing out the existence of a supposed conspiracy plot behind Espinar’s case: “Yesterday he shielded himself from a supposed theory of conspiracy so as not to lose internal support” (idem).

The media of the PRISA Group are frequently mentioned in Público when it is pointed out who is responsible for the attacks suffered by the leaders of Podemos. An example of this is the news about the alleged manipulation of a phrase of Iglesias in an information of the SER Chain, whose owner is very explicit as to the intention of this medium to adulterate the message of Pablo Iglesias: “The SER shortens a phrase of Pablo Iglesias on feminism in a headline and is forced to correct it”( Público.es , 11/29/2016). In this news, however, there is no reference to the fact that the message of the leader of Podemos in its entirety, beyond the version reproduced by Cadena SER, was also harshly criticized even by a sector of the feminist movement.

The mentioned frame of responsibility has certain elements in common with one of the functions that, according to Robert M. Entman, can play a frame: that of the diagnosis of causes. According to this author, the four functions that a frame can play are the following (1993, p.52):

– Define problems: that is, determine what a causal agent is doing and with what costs and benefits.

– Diagnose the causes: identify the forces that generate the problem

– Issuing moral judgments: this implies the evaluation of the causal agents and their effects.

– Suggest solutions: offer and justify treatments for problems and predict their likely effects.

According to this definition, in the Público newspaper the presence of the function of diagnosing the causes is usual, and it appears continuously in those reports that address the criticisms expressed against Pablo Iglesias and other representatives of Podemos, which are usually linked to a supposed campaign of insults against this political leader and against Podemos. In this way, what Entman (1993, p.53) pointed out when describing the operation of the frames is being produced: certain fragments of information on a topic are underlined, thus increasing its relevance. In this case, the importance of some supposed external agents as cause of the problems that affect Podemos or its leader is underlined.

From Público it is emphasized in those declarations of the secretary general of Podemos and other representatives of the formation, that point out the existence of hidden interests behind each one of the comments that are not to the liking of Iglesias. A paradigmatic example of this is the news of November 12, where a diagnosis of the causes of the polemics that affect Podemos is carried out. At the origin of these problems certain media are located, so that the journalist Eduardo Inda is accused of carrying out a continuous defamation against Iglesias: “It seemed that Eduardo Inda was once more insulting without answering by another falsehood published with the intention of defacing Pablo Iglesias [...]” (Bayo and López, Público.es , 11/12/2016). The authors of the information, in addition, assure that Inda will take no time in “re-insulting Podemos” (idem ). In this information, therefore, the idea of the existence of some victims (Pablo Iglesias and Podemos) who suffer the harassment of a means of communication directed by Eduardo Inda ( OK Diario ) is underlined.

The vocabulary used in many of the Público’s news also invites us to suspect the existence of a plot against Podemos. An example of this is the frequency of the use of the verb denounce to refer to the opinions of the leaders of this party on the origin of the polemics that affect them. Here are some cases in which this verb is used:

– When Espinar’s vision is summarized on the controversy generated by the issue of the sale of his home: “He denounces that the Prisa group has tried to finish his political career during this internal campaign” (López de Miguel, Público.es, 09 / 11/2016).

– In the headline where the statements of Iglesias on the matter of Espinar stand out: “Pablo Iglesias denounces that the controversy of Espinar is an attack against him to weaken his leadership” ( Público.es , 03/11/2016).

– In the entry of the information about the supposed persecution suffered by Victoria Rosell: “the magistrate denounces a ‘strategy of harassment’ against her from the moment Pablo Iglesias announced that she would be responsible for Justice” (Pérez, Público.es, 29 / 11/2016).

In these situations, the use of the verb to denounce can be interpreted as meaning “to participate or officially declare the illegal, irregular or inconvenient state of something”, which is one of the meanings contained in the definition of the Dictionary of the Spanish language (DLE)). This meaning implies a greater dose of objectivity than that which corresponds to other verbs such as think, believe or consider, which might be more appropriate if we bear in mind that the opinions of certain representatives of a political formation are being reproduced. On the other hand, the frame of responsibility is also present in the news about the action of the leader of Podemos Carolina Bescansa (1) referred to the conciliation of family and work life. The newspaper Público presents the criticisms against Bescansa as a persecution against Podemos. Sometimes, the latter is appreciated by the use of certain expressions that highlight the existence of a large number of media and political groups that are positioned against such political formation, as in the following example: “The gesture of Bescansa brought him a cataract of criticism and insults “(Público.es, 11/17/2016). Other times, the discourse about the conspiracy against Podemos appears in the headline of the news, as in the following example, in which the words of Bescansa are reproduced about the existence of a supposed repudiation of the ideas that defend their political formation: “It is clear that the scandal when I took my son to Congress was due to the rejection of Podemos” (López de Miguel, Público.es, 11/18/2016). In the body of the interview with this leader of Podemos, she is also given the opportunity to denounce the behavior of “different opinion makers, parties and opinion leaders” (idem), who criticized her harshly only because they reject the ideology that she represents.

(1) Carolina Bescansa went with her baby and performed different activities with him in her arms during the opening of the General Courts corresponding to the XI Legislature, in January, 2016.

There are numerous informative texts of Público where the opinions of the cupola of Podemos are reproduced on the supposed conspiracy of the mass media against this formation. Iglesias, for example, links media criticism to his party with the politically incorrect attitude adopted by the leaders of Podemos. In the news of November 24, Iglesias analyzed the consequences for his party of not participating in the minute of silence due to the death of Senator Rita Barberá: “This has been a media lynching, but I in the street find congratulations “(López de Miguel, Público.es , 11/24/2016).

The opening of a disciplinary file to the judge and ex-deputy of Podemos Victoria Rosell is also presented in Público as a consequence of the political persecution carried out against the leaders of Podemos. On November 28, the link between Rosell’s acceptance as a candidate for the Congress for the “purple” formation and the beginning of her judicial problems, through the use of the adverbial locution, nothing more is underlined: “As soon as we accept to be a candidate for Podemos by Las Palmas, Victoria Rosell saw her life complicated with the opening of an investigation by the Prosecutor’s Office “(Pérez, Público.es, 11/28/2016). In the body of this news, in addition, the movements carried out by those who have taken legal action against this judge are reported in great detail. The next day, Público highlights in the headline and in the entry of the news Rosell’s statements about the alleged political persecution suffered by this ex-deputy. While in the entry there is talk of “strategy of harassment” against the judge, the headline thus summarizes Rosell’s vision on this matter: “Rosell: ‘I have suffered a PP political persecution for a year” (Pérez, Público .es, 11/29/2016).

On the other hand, Público attributes the origin of the accusations of illegal funding of Podemos to a pact established between a sector of the National Police Force and certain journalists like Eduardo Inda, whose aim is the loss of prestige of Pablo Iglesias and Podemos. The following fragment, where montage is directly mentioned, is an example of the definition of this situation as the consequence of a supposed media-police conspiracy against iglesias: “ Only in 2016, Pablo Iglesias and Podemos have suffered different police and media montages that have gone from assuring that they are financed illegally through Iran and Venezuela, to try to link him with ETA or to discredit his family “(Público.es , 11/01/2016).

The rest of the thematic frames related to the frame of responsibility usually place the business, financial or political elites as responsible for the matters denounced by the representatives of Podemos. Such is the case of the electricity companies in the matter of the placement of certain former ministers or former presidents in their boards of directors; certain sectors of the judiciary on the issue of the expulsion of Lieutenant Luis Gonzalo Segura; or some political parties like the PP or the PSOE in the matter of the ratification of the commercial agreement between the European Union and Canada, called CETA (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement ). In all these occasions, the opinions of the leaders of Podemos about the aforementioned responsibility of these groups are highlighted in Público , either by dedicating an important space in the body of the news, or by including them in the headline of the information.

The frame of morality is less important than the two aforementioned frames, since it only appears in ten news items. In some occasions, the ethical component of the proposals of the Podemos representatives is highlighted, as when the actions carried out to avoid the aforementioned appointment of former Minister Jorge Fernández Díaz are described. In this case, from Público it is emphasized that it is the deputies of Unidos Podemos who have prevented said appointment, before the ambiguous behavior of the Socialist Group in the Congress on this matter: “it has been the group of Unidos Podemos who has formally requested a report about the suitability of the former minister “(Público.es, 11/16/2016). The morality of other proposals, such as the requirement that the body of women is not used as an advertising claim (Público.es, 06/11/2016); or the demand for the end of energy poverty (Plaza, Público.es, 11/19/2016) is also highlighted.

The frame of economic consequences is present in seven news, and is usually related to the effects of the decisions of large companies on the economic situation of the working class, or with the proposals of Podemos to guarantee the sustainability of pensions (Otero, Público.es, 11/05/2016).

Finally, the frame of human interest also appears only in seven news units. They highlight the human side of certain issues, such as when Ramón Espinar’s words about the controversy of his home are reproduced, and he compares his situation with that of any young person who only aspires to become independent: “What is the problem? ethical that a kid asks 60,000 euros to his family to buy a flat? “(López de Miguel, Público.es, 11/02/2016). Another example of this kind of framing is the reference to the old woman who died in Reus because of the fire caused by a candle, after Gas Natural cut off her electricity supply. In the aforementioned news, the phrase of Iglesias is repeated twice in which he suggests that a minute of silence should be observed in the Congress of Deputies for the victims of energy poverty (López de Miguel, Público.es, 23/11 / 2016).

4.2. The critical approach of the newspaper El País

The frame of responsibility in the analyses units of El País is very frequent, with a presence in 40.4% of the sample, but it is associated with an idea radically opposed to that of the Público newspaper. In the daily newspaper of the Grupo PRISA, allusions to the responsibility of Pablo Iglesias and other leaders of Podemos in the dissemination of the existence of a supposed “ conspiracy theory “ against this political formation, which is at the origin of criticism, are ongoing. to this political formation.

Unlike the framing of the Público newspaper, the El País discourse usually introduces the opinions of the Podemos representatives about the alleged orchestrated conspiracies against them, through a series of expressions through which the real existence of said machinations is questioned. On the contrary, the impression that is transmitted is that it is, rather, a distraction maneuver carried out by some of its leaders. Francesco Manetto, for example, uses these words to convey Ramón Espinar’s vision of the controversy surrounding the purchase and sale of his home: “The senator, who confirmed the veracity of the information, presented himself as a victim of the economic powers that they tried to influence the internal process of Podemos “(Manetto, Elpais.com, 11/10/2016 ). In fact, there are 7 (14.9% of the total units) information on the Espinar housing issue where the responsibility framework is used to blame it, or to have benefited from the sale of a subsidized home, or else to devise a theory of conspiracy against him to, supposedly, prejudice his candidacy for the primary elections of Podemos Madrid.

Below are other examples of the mention, both explicit and implicit, to this theory of conspiracy in El País:

– When the reactions of the leadership of Podemos to the controversy on the flat of Espinar are reported: “[...] the main leaders of the party [...] resorted to a wide range of disqualifications [...] to contain the scope of the news” ( García de Blas, Elpais.com , 11/03/2016 [b]). In this case, the manipulative purpose of the attacks directed against the media groups that publish information about the sale of the senator of Podemos is explicitly expressed.

– In describing the dissemination of this conspiracy theory as a “strategy”: “The strategy of the Pabloites after the outbreak of the Senator’s case is to try to use it in their favor, presenting it as a kind of intervention in the process led by the PRISA group “(García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/05/2016 [b]).

– In some cases, the mention of this conspiracy theory also appears in the headline of the news: “Errejón rejects the theory of ‘black hand’ or ‘conspiracy’ against Espinar” (Manetto, Elpais.com, 11/08/2016 ); “Podemos conclude a campaign marked by theories of conspiracy” (Manetto, Elpais.com, 11/09/2016 [b]). The attribution of responsibility for the dissemination of the idea of collusion to the sector headed by Pablo Iglesias is reinforced in these texts where it is emphasized that the Íñigo Errejón’s sector rejects the aforementioned supposedly invented theories.

In contrast to the discourse of news Público addressing the issue of the alleged conspiracy against Podemos, in El País it is usual the presence of different opinions of different sign affecting the party. An example of the latter is the information from November 3 (García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/03/2016 [ b ]) on the purchase and sale of Espinar’s home. In it appear, on the one hand, the defense statements of Espinar from Pablo Iglesias, Íñigo Errejón and Rita Maestre; and, on the other hand, the negative opinions on the performance of the Madrid senator, expressed by Cayo Lara and Gaspar Llamazares. Likewise, we must highlight the differences in the way of preparing the news referring to the statements of Iglesias about Donald Trump. In Público (Público.es, 11/28/2016) they are limited to underlining the differences between the ideology of Podemos and that of Trump, based on the affirmations of the leader of this party. On the contrary, in the El País information on this subject, different opinions of experts are also collected, which expose, not only the differences, but also some similarities between right and left populisms. In this diary an approach is adopted, which emphasizes the problems that have generated to Iglesias his insistence on defending populism as a way of doing politics, by the analogies that arose between Trump and Podemos: “Pablo Iglesias hurried, after knowing the result, to mark distances with the republican tycoon, openly showing his contempt “(García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/11/2016). In this case, it means that Iglesias called Trump a fascist.

The frame of responsibility is also used in El País to point out those leaders of Podemos who are supposedly in the origin of the internal conflicts of this formation in different territories. In this sense, the authoritarian leadership style of the leadership of this party is often highlighted in places like Canarias (Santana, Elpais.com, 04/11/2016, 11/30/2016), or the corrupt practices of some posts of Podemos in Baleares (Bohórquez, Elpais.com, 11/07/2016).

The conflict frame is the most used in the El País sobre Podemos news, and is present in 93.6% of the units analyzed, as can be seen in table 1. The idea associated with this frame the appears with greater frequency is that the party is very polarized, given that there are, above all, two very confronted positions, led by Iglesias and Errejón. In fact, almost half of the news highlight such confrontation, since this idea is present in 48.9% of the units in the sample.

The confrontation between the two factions mentioned is underlined in some headlines such as the following: “The ‘Espinar case’ muddies the internal dispute in Unidos Podemos” (García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/05/2016 [a]); “Iglesias and Errejón fight the key battle in Madrid” (García de Blas, Elpais.com, 06/11/2016); “Errejón tries to gain time and his followers encourage him to give the battle” (García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/13/2016); or “Iglesias challenges Errejón to discuss their political differences before reaching an agreement” (García de Blas, Elpais.com , 11/17/2016). In the news, in general, the position of Errejón is described as moderate, as evidenced by the fact that in some headlines the political differences between Izquierda Unida and the Errejón sector are emphasized, or it is emphasized that the more radical position of Iglesias take away the possibilities of electoral growth to its formation.

In the case of El País, unlike Público, the description of the internal conflict in Podemos is carried out through a vocabulary that highlights the confrontation between the different sectors of the political formation. The tense adjective and the verb to tense, for example, is frequently used in the information of this newspaper to allude to the problems arising during the process of primary elections of Podemos for the Community of Madrid or for the state direction. In the following example, this process of primaries is linked to the increase in internal tension, with these words: “[...] a process of autonomic primaries that has been tensing the relations between the different families of the party for two months” (Manetto, Elpais. com, 11/9/2016 [b]).

In El País, in addition, the verbs that accompany the conspiracy theory disseminated by some leaders of Podemos, unlike those used in Público, detract from the aforementioned conspiracy. Such is the case of the verb to shield- according to the definition of the DLE: Said of a person: Use of some means, favor and shelter to justify himself, leave the risk or avoid the danger that is threatening him-, which is used to refer to the vision of Iglesias on Espinar’s housing information: “Yesterday he shielded himself in a supposed conspiracy theory so as not to lose internal support” (García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/03/2016 [ a ]).

When informing about the internal problems of Podemos, expressions that reinforce the idea that there is a climate of confrontation within this formation, such as the nouns crisis, pulse , dispute , storm or contest , or the verbal phrase smooth things over. A paradigmatic case is the information on the precautionary suspension of militancy of the president of the Balearic Parliament, Xelo Huertas. In it the term crisis appears six times, -in the headline it is also present-, in addition to the expression storm and the verbal phrase open the box of the thunders: “The crisis opened in Podemos Baleares [...] has opened the box of the thunders and has transferred part of the storm to the government pact “(Bohórquez, Elpais.com , 11/08/2016). Other expressions with warmongering connotations that reinforce the image of struggle for power are, for example, the following: open wounds (García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/16/2016); fratricidal war (García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/17/2016); or battle (García de Blas, Elpais.com , 06/11/2016, 11/07/2016, 11/13/2016, Manetto, Elpais.com , 11/10/2016, 12/11/2016).

Finally, it is worth highlighting the great difference existing with Público’s vision of the supposed identification of Podemos with “the people” against the power of the elites. In El País, this discourse is interpreted as a mere strategy devised by Pablo Iglesias to get more votes for the goal of becoming the main leftist force. Thus, Manetto uses the verb to stage to introduce the idea of Iglesias’s defense of the politically incorrect: “The leader of Podemos, Pablo Iglesias, staged his opposition on Thursday to the rest of political formations and claimed the option of being politically incorrect. in its institutional activity “(Manetto, Elpais.com, 11/25/2016). This approach contrasts with that of Público, which limits itself to reproducing the words of Iglesias without referring to the intentions that are hidden behind the radical nature of his discourse. This departure from moderation is also interpreted in other information as a maneuver to expand his electorate, as seen in the following passage:

After the general elections of June 26, in whose campaign Podemos and Iglesias itself sought an image of moderation, Iglesias has gone on to defend that the party has to develop a harsh and disobedient style, among other reasons because that is the European trend that triumphs today (Manetto, Elpais.com, 11/09/2016 [ a ]).

On the other hand, El País does not direct the informative attention towards the work of Podemos opposition before the policies of the PP, but, on the contrary, is critical of the radical position of Iglesias against Errejón’s moderation. In this sense, we can appreciate the presence of data on the negative consequences of the confrontation strategy of the leader of Podemos, as in this case: “The rejection of a part of the population to Podemos has grown ten points in its two years of life [...] Pablo Iglesias is the second worst valued leader “(García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/21/2016).

As for the morality framework, it is present in 14.9% of the units of analysis. It is used, mainly, to question the behavior of Ramón Espinar when he sold his house in Alcobendas for the maximum price set, with a net benefit of some 20,000 euros. In fact, one of the news reports that this senator, paradoxically, has been very critical of real estate speculation in the Community of Madrid, as stated in this paragraph: “The leader of Podemos is an expert in urban planning and public housing. [...] criticizing with special hardness the speculation and what he described as ‘looting of public housing in the Community of Madrid’ “(García de Blas, Elpais.com, 11/03/2016 [ c ]). The frame of morality is also present when we report on the management style of some territorial leaders of Podemos or when it refers to the actions for which Judge Victoria Rosell is being investigated.

Table 1. Weight of the different frames according to the model of Semetko and Valkenburg

Source: own elaboration.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In the Público newspaper we can see a series of discursive tendencies that lead us to conclude that in this environment there is a general framework favorable to the political formation Podemos.

The examination of the news frames of the journalistic pieces has allowed us to reach the conclusion that in this newspaper the vision of those representatives of Podemos who interpret the criticisms of their political formation as an organized conspiracy is placed in a prominent place of their information. from certain political and media groups to weaken this political formation. This vision is transmitted in a large number of occasions through the framework of responsibility, and the consequent attribution of responsibility for the problems of Podemos to elements external to said party.

In fact, the frame of responsibility is related, in a large number of occasions, to a series of ideas that reinforce the discourse of the leaders of Podemos, who attribute responsibility for the controversies that affect this formation, to certain media groups and politicians who conspire against them.

In other cases, the aforementioned frame is linked to the idea that the culprits of the issues denounced by Podemos are certain elites pointed out by the representatives of that party. The idea mentioned is highlighted in Público by placing the opinions of the leaders of Podemos on these power groups, in a preferred place of the news.

Regarding the conflict frame, in Público a series of arguments are used through which the positive elements of the political action of Podemos are underlined. An example of this is the focus on the features that distinguish this formation from traditional parties; or the idea that Podemos represents the true political opposition to the PP; or the identification of Podemos with the people, before the economic and political elites. Finally, we must emphasize that the internal conflict that affects this formation is described as a mere confrontation of ideas.

Based on the analysis carried out, it could be concluded that what stands out in the approach adopted in the information about Podemos in the newspaper Público is the attempt to delegitimize most of the criticisms leveled at Pablo Iglesias or Podemos, from various media and political formations.

From all that has just been exposed, it can be inferred, therefore, that the general interpretative framework of the Público newspaper is uncritical with the discourse elaborated by the Podemos cupolacupola and does not question the official narrative of this political formation. On the contrary, from Público the official story of Podemos is usually reinforced, like that of the confrontation with the traditional political forces or that of the conspiracy against Podemos.

On the other hand, in the newspaper El País the presence of the responsibility framework is also frequent, but it is associated with a discourse very different from that which characterizes the newspaper Público. In El País, through the framework of responsibility, the main leaders of Podemos are identified as the creators of the different conspiracy theories against them that have been propagated from this political party in recent months.

The frame of conflict is often associated with the idea that in Podemos there is a strong polarization between the sectors led by Íñigo Errejón and Pablo Iglesias. Another idea related to this framework is that of the confrontation between this formation and the business and political elites, but from El País it is interpreted as a strategy elaborated by the Podemos cupola to become the main leftist force.

In general terms, therefore, the official discourse of Podemos on the problems that affect this formation is continuously questioned in the newspaper El País. In this way, it can be concluded that the general interpretative framework of El País is critical with the decisions and the official discourse of Podemos. In addition, this newspaper transmits the image that Podemos is a party immersed in a strong internal conflict, and little attention is paid to the daily political activity and the initiatives carried out by this formation.

From the foregoing it is clear, therefore, that El País and Público differ greatly in the definition of the problems that affect Podemos. In this sense, the analysis of the discourse of the newspapers mentioned about this political formation reveals the existence of two general interpretive frameworks: while El País adopts a critical approach to this party, the newspaper Público is generally favorable to the discourse and the decisions taken by Podemos.

REFERENCES

1. Araque P (17 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias: “Patriotismo es defender los derechos civiles”, no acudir a ‘besamanos y desfiles’”. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/iglesias-patriotismo-defender-derechos-civiles.html.

2. Ardèvol-Abreu A (2015). Framing o teoría del encuadre en comunicación. Orígenes y panorama actual en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 70, 423-450.

3. Arroyas E, Pérez-Díaz PL (2016). La nueva narrativa identitaria del populismo: un análisis del discurso de Pablo Iglesias (Podemos) en Twitter. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, 15, 51-63.

4. Bateson G (1955). A theory of play and fantasy. A report on theoretical aspects of the project for study of the role of paradoxes of abstraction in communication, Psychiatric Research Reports, 2, 39-51. (Reimpreso en 1972. Bateson G, Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology (pp. 177-193). San Francisco: Chandler Publishing Company).

5. Bayo C, López P (12 de noviembre de 2016). El juez acusa a Inda de “mala fe procesal” en su recusación previa al juicio por injuriar a Pablo Iglesias. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/juez-acusa-inda-mala-fe.html.

6. Berganza MR (2003). La construcción mediática de la violencia contra las mujeres desde la Teoría del Enfoque. Comunicación y Sociedad, 16(2):9-32.

7. Bohórquez L (7 de noviembre de 2016). Podemos suspende a la presidenta del Parlamento balear por un caso de amaño. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/07/actualidad/1478520681_733618.html

8. Bohórquez L (8 de noviembre de 2016). La crisis de Podemos en Baleares tensa la cuerda del pacto de Armengol. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/08/actualidad/1478610313_783421.html

9. Capilla M (2014). Los hombres clave de Podemos. El siglo de Europa, nº 1.066, 26-28. Recuperado de http://www.elsiglodeuropa.es/siglo/historico/2014/1066/1066pol_Podemos.pdf

10. Cela D (4 de noviembre de 2016). Teresa Rodríguez defiende volver al Podemos del 15-M y sus críticas piden más trabajo institucional. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/teresa-rodriguez-defiende-volver-al.html

11. Entman R (1993). Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4):51-58.

12. Gallardo-Camacho J, Lavín E (2016). El interés de la audiencia por las intervenciones televisivas de Pablo Iglesias: estrategia comunicativa de Podemos. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 22(1):273-286.

13. García-de-Blas E (3 de noviembre de 2016a). Iglesias cree que las críticas a Espinar buscan debilitar su liderazgo. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/03/actualidad/1478177149_165220.html

14. García-de-Blas E (3 de noviembre de 2016b). La compraventa de Ramón Espinar tensa la disputa de Podemos en Madrid. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/02/actualidad/1478121558_936748.html

15. García-de-Blas E (3 de noviembre de 2016c). Ramón Espinar vendió su vivienda protegida a los pocos meses de comprarla. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/02/actualidad/1478082072_427232.html

16. García-de-Blas E (5 de noviembre de 2016a). El “caso Espinar” enturbia la disputa interna en Unidos Podemos. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/04/actualidad/1478287636_692908.html

17. García-de-Blas E (5 de noviembre de 2016b). Espinar: “Es una barbaridad lo que han hecho conmigo”. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/05/actualidad/1478349124_835866.html

18. García-de-Blas E (6 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias y Errejón libran la batalla clave en Madrid. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/05/actualidad/1478372320_110264.html

19. García-de-Blas E (7 de noviembre de 2016). El feminismo y las redes, bazas de los errejonistas en la batalla de Madrid. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/06/actualidad/1478456245_179819.html

20. García-de-Blas E (11 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias defiende un populismo de izquierdas frente a Trump. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/10/actualidad/1478735528_705682.html

21. García-de-Blas E (13 de noviembre de 2016). Errejón intenta ganar tiempo y sus afines le animan a dar la batalla. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/13/actualidad/1479061394_609516.html

22. García-de-Blas E (16 de noviembre de 2016). Espinar ofrece un puesto en su Ejecutiva a los errejonistas. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/16/actualidad/1479308594_728994.html

23. García-de-Blas E (17 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias reta a Errejón a discutir sus diferencias políticas antes de llegar a un acuerdo. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/16/actualidad/1479327120_992360.html

24. García-de-Blas E (21 de noviembre de 2016). Los votantes desencantados del PSOE rechazan la opción de Podemos. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/19/actualidad/1479569166_307263.html

25. Goffman E (1974). Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. New York: Harper and Row.

26. Grossi G (2007). La opinion pública. Teoría del campo demoscópico. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

27. Iyengar S (1994). Is Anyone Responsible?: how television frames political issues. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

28. Kim SH, Scheufele DA, Shanahan J (2002). Think about it this way: attribute agenda-setting function of the press and the public’s evaluation of a local issue. Journalism and Mass Communication Quartely, 79(1):7-25.

29. Lang GE, Lang K (1983). The Battle for Public Opinion: The President, the Press and the Polls during Watergate. New York: Columbia University Press.

30. López-de-Miguel A (2 de noviembre de 2016). Espinar asegura que vendió su casa de Alcobendas porque “no podía pagarla”. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/espinar-asegura-vendio-casa-alcobendas.html

31. López-de-Miguel A (9 de noviembre de 2016). Ramón Espinar: “Errejón no va a quedar debilitado cuando yo gane”. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/ramon-espinar-errejon-no-quedar.html

32. López-de-Miguel A (18 de noviembre de 2016). Bescansa: “Está claro que el escándalo cuando llevé a mi hijo al Congreso obedecía al rechazo a Podemos”. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/bescansa-claro-escandalo-lleve-mi.html

33. López-de-Miguel A (23 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias: “El truco de las eléctricas es comprar ministros y expresidentes”. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/iglesias-truco-electricas-comprar-ministros.html

34. López-de-Miguel A (24 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias pide abandonar la corrección política: “Basta ya de hipocresía”. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/iglesias-pide-abandonar-correccion-politica.html

35. López-de-Miguel A (28 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias, con los trabajadores de telemárketing en huelga: “Ellos son la oposición social al PP”. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/iglesias-trabajadores-telemarketing-huelga-son.html

36. Manetto F (8 de noviembre de 2016). Errejón rechaza la teoría de “mano negra” o “conspiración” contra Espinar. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/08/actualidad/1478565870_787217.html

37. Manetto F (9 de noviembre de 2016[a]). Iglesias defiende “hablar claro” y huir de la moderación para evitar “nuevos tipos de fascismo”. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/09/actualidad/1478682302_958545.html

38. Manetto F (9 de noviembre de 2016[b]). Podemos concluye una campaña marcada por teorías de la conspiración. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/08/actualidad/1478634836_686456.html

39. Manetto F (10 de noviembre de 2016). La alta participación en las primarias de Podemos Madrid dispara la inquietud por el resultado. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/10/actualidad/1478778811_797526.html

40. Manetto F (12 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias y la gasolina anticapitalista. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/11/actualidad/1478892239_013073.html

41. Manetto F (25 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias ve inútil apelar al “concepto burgués de clase media” y reivindica lo políticamente incorrecto. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/24/actualidad/1480018780_925881.html

42. McCombs M (2006). Estableciendo la agenda. El impacto de los medios en la opinión pública y en el conocimiento. Barcelona: Paidós.

43. McCombs M, Shaw D (1972). The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2):176-187.

44. McCombs M, Shaw D, Weaver D (1997). Communication and democracy: Exploring the intellectual frontiers in agenda-setting theory. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

45. Otero J (5 de noviembre de 2016). Las fórmulas de Podemos para evitar que el sistema de pensiones colapse. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/economia/formulas-evitar-sistema-pensiones-colapse.html

46. Pérez J (29 de noviembre de 2016). Rosell: “Sufro desde hace un año una persecución política del PP”. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/tribunales/rosell-sufro-ano-persecucion-politica.html

47. Pérez J (28 de noviembre de 2016). El CGPJ abre expediente disciplinario a la juez Victoria Rosell. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/cgpj-abre-expediente-disciplinario-juez.html

48. Plaza S (19 de noviembre de 2016). La gente se muere sin luz y las eléctricas ganan millones. Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/no-normal-muera-gente-no.html

49. Price V, Tewksbury D, Powers E (1997). Switching trains of thought: the impact of news frames on readers’ cognitive responses. Communication Research, 24, 481-506.

50. Publico.es (1 de noviembre de 2016). Iglesias preguntará en el Congreso a la vicepresidenta sobre el ‘dossier del CNI’. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/exige-comparezca-director-del-cni.html

51. Publico.es (2 de noviembre de 2016[a]). El PP no reconoce a Podemos como líder de la oposición: “No queríamos el ‘sorpasso’”. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/pp-no-reconoce-lider-oposicion.html.

52. Publico.es (2 de noviembre de 2016[b]). “Iglesias, tras la información sobre Espinar: ‘Los aparatos de Cebrián, a saco en nuestras primarias”. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/iglesias-informacion-espinar-aparatos-cebrian.html

53. Publico.es (3 de noviembre de 2016). Pablo Iglesias denuncia que la polémica de Espinar es un ataque contra él para debilitar su liderazgo. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/pablo-iglesias-denuncia-polemica-espinar.html

54. Publico.es (6 de noviembre de 2016). Podemos exige que no se utilice el cuerpo de la mujer como reclamo publicitario en eventos deportivos. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/exige-no-utilice-cuerpo-mujer.html

55. Publico.es (14 de noviembre de 2016). Podemos devuelve los préstamos con los que sus bases financiaron su campaña de las elecciones del 20-D. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/devuelve-prestamos-bases-financiaron-campana.html

56. Publico.es (16 de noviembre de 2016). El PSOE se arroga ahora el veto a Fernández Díaz. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/psoe-arroga-ahora-veto-fernandez.html

57. Publico.es (17 de noviembre de 2016). Bescansa vuelve a visibilizar en el Congreso el problema de la conciliación. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/bescansa-vuelve-visualizar-congreso-problema.html

58. Publico.es (19 de noviembre de 2016). Los líderes de Unidos Podemos comparan las revelaciones de Suárez a Prego con la situación actual. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/lideres-unidos-expresan-twitter-impresiones.html

59. Publico.es (28 de noviembre de 2016). Pablo Iglesias: “Podemos llamar fascista a Donald Trump”. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/pablo-iglesias-llamar-fascista-donald.html

60. Publico.es (29 de noviembre de 2016). La SER acorta una frase de Pablo Iglesias sobre el feminismo en un titular y se ve obligada a corregirlo. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/economia/comunicacion/acorta-frase-iglesias-feminismo-titular.html

61. Sádaba MT (2001). Origen, aplicación y límites de la “teoría del encuadre” (framing) en comunicación. Comunicación y Sociedad, 14(2):143-175.

62. Santana T (4 de noviembre de 2016). Podemos Tenerife dimite en bloque por el estilo de dirección “autoritario” y “arbitrario”. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/04/actualidad/1478262761_113135.html

63. Santana T (30 de noviembre de 2016). El Consejo Ciudadano de Podemos en Gran Canaria se disuelve tras 15 dimisiones. Elpais.com. Recuperado de http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2016/11/30/actualidad/1480522979_074535.html

64. Semetko HA, Valkenburg PM (2000). Framing European Politics: A Content Analysis of Press and Television News. Journal of Communication, 50(2):93-109.

65. Scheufele D (1999). Framing as a Theory of Media Effects. Journal of Communication, 49(1):103-122.

66. Tannen D (1993). Introduction. en D. Tannen, (Ed.). Framing in Discourse (pp. 3-13). New York: Oxford University Press.

67. Vargas J (16 de noviembre de 2016). Podemos exige a Bruselas que la patronal del telemárketing cumpla la normativa laboral europea Publico.es. Recuperado de http://www.publico.es/politica/exige-bruselas-patronal-del-telemarketing.html

68. Zhou Y, Moy P (2007). Parsing Framing Processes: The Interplay Between Online Public Opinion and Media Coverage. Journal of Communication, 57, 79-98.

AUTHOR

Manuel Peris Vidal

Doctor from the Pablo de Olavide University (Seville), with a thesis on the representation of male chauvinist violence in the newspaper El País. He has published numerous articles on the journalistic treatment of gender violence.

https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=h7yknjAAAAAJ&hl=es