doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.141.139-154

RESEARCH

INFLUENCE AND MEDIA IMPACT OF THE “FACE TO FACE” DEBATES HELD BEFORE THE GENERAL ELECTIONS IN 2008 IN SPAIN: JOSÉ LUIS RODRÍGUEZ ZAPATERO (PSOE) VS MARIANO RAJOY (PP)

INFLUENCIA Y REPERCUSIÓN MEDIÁTICA DE LOS DEBATES “CARA A CARA” CELEBRADOS ANTE LAS ELECCIONES GENERALES DE 2008 EN ESPAÑA: JOSÉ LUIS RODRÍGUEZ ZAPATERO (PSOE) VS MARIANO RAJOY (PP)

INFLUÊNCIA E REPERCURSÃO MEDIÁTICA DOS DEBATES CARA A CARA CELEBRADOS ANTE AS ELEIÇÕES GERAIS DE 2008 NA ESPANHA: JOSÉ LUIS RODRIGUEZ ZAPATERO (PSOE) VS MARIANO RAJOY (PP)

María Gallego-Reguera1 PhD in Information Sciences and a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism. Expert in political and institutional communication. She has published several books and articles on voter debates and participated in organizing the debates between presidential candidates of the Government in Spain in the general elections in 2008, 2011, 2015 and 2016 as a member of the Academy of Sciences and Arts of TV. Professor of communication at Menéndez Pelayo International University, University of Salamanca and University of Lleida, among others. In addition, she has worked professionally as a journalist in several media. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3526-6434. https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=Fj1ZnZoAAAAJ&hl=es. https://independent.academia.edu/Mar%C3%ADaGallego2

Asunción Bernárdez-Rodal2 Professor of the Department of Journalism III School of Information Sciences at the Complutense University of Madrid. She has been a Professor of Political Communication and specializes in gender studies and communication. Her latest book published in Fundamentos Publishing House is Women in the Media (s): proposals to analyze mass communication with a gender perspective (2015). Researcher ID G-8284-2015. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4081-0035

1Next International Business School/Internacional University Menéndez Pelayo. Spain

2University Complutense of Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the study of the “face to face” electoral debates held in Spain on the occasion of the 2008 general elections between José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (PSOE) and Mariano Rajoy (PP) and organized by the Academy of Sciences and the Television Arts. These debates have been selected for an in-depth study because they mean the return of debates in Spain fifteen years after the last face-to-face in a general election, held in 1993 between the then President of the Government, Felipe González (PSOE) , and José María Aznar (PP). The debates of 2008 became a historic event with a great impact on both the national and international media, which made a relevant coverage of it. Although the broadcast of the debates scarcely modified the vote of citizens, it did encourage electoral participation, which always alters the distribution of seats. Holding them was important for the process of democracy, since they motivated electoral participation, and for the information of citizens, who took a great interest in both political television programs.

KEYWORDS: Debates, Political communication, General Elections, Television, Face to face, José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, Mariano Rajoy

RESUMEN

Este artículo se centra en el estudio de los debates electorales “cara a cara” celebrados en España con motivo de las elecciones generales de 2008 entre José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (PSOE) y Mariano Rajoy (PP) y organizados por la Academia de las Ciencias y las Artes de Televisión. Se han seleccionado estos debates para su estudio en profundidad porque significan el retorno de los debates en España transcurridos quince años después los últimos cara a cara en unos comicios generales, los celebrados en 1993 entre el por entonces presidente del Gobierno, Felipe González (PSOE), y José María Aznar (PP). Los debates de 2008 se convirtieron en un suceso histórico con una gran repercusión tanto en los medios nacionales como en los internacionales, que realizaron una relevante cobertura del mismo. Aunque la emisión de los debates apenas modificó el voto de los ciudadanos, sí incentivó la participación electoral, lo que siempre altera el reparto de escaños. Su celebración resultó importante para el proceso de la democracia, ya que motivaron la participación electoral, y para la información de los ciudadanos, quienes demostraron un gran interés por ambos programas políticos de televisión.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Debates, Comunicación política, Elecciones Generales, Televisión, Cara a cara, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, Mariano Rajoy

RESUMO

Este artigo centra-se no estudo dos debates eleitorais cara a cara celebrados na Espanha com motivo das eleições gerais de 2008 entre José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero (PSOE) e Mariano Rajoy (PP) e organizados pela Academia de Ciências e Artes de Televisão. Foram selecionados estes debates para seu estudo em profundidade porque significam o retorno dos debates na Espanha transcorridos quinze anos depois dos últimos cara a cara em comícios gerais, celebrados em 1993 por Felipe González (PSOE), na época presidente do Governo, e José Maria Aznar (PP). Os debates de 2008 converteram-se em um acontecimento histórico com uma grande repercussão tanto em âmbito nacional como internacional que realizaram uma relevante cobertura. Ainda que a emissão dos debates apenas modificasse os votos dos cidadãos, foi incentivado a participação eleitoral, o que sempre altera a distribuição das cadeiras no congresso. Sua celebração resultou importante para o processo da democracia, já que motivaram a participação eleitoral, e para a informação dos cidadãos que demonstraram um grande interesse por ambos os programas políticos de televisão.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Debates, Comunicação política, Eleições Gerais, Televisão, Cara a cara, José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, Mariano Rajoy

Received: 17/07/2017

Accepted: 20/09/2017

Published: 15/12/2017

Correspondence: María Gallego Reguera. m.gallego@nextibs.com

Asunción Bernárdez Rodal. asbernar@ccinf.ucm.es

How to cite the article

Gallego Reguera, M., Bernárdez Rodal, A. (2017). Influence and media impact of the “face to face” debates held before the general elections in 2008 in Spain: José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (PSOE) vs Mariano Rajoy (PP) [Influencia y repercusión mediática de los debates “cara a cara” celebrados ante las elecciones generales de 2008 en España: José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (PSOE) vs Mariano Rajoy (PP)].

Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 141, 139-154

doi http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2017.141.139-154

Recuperado de http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1098

1. INTRODUCTION

The general elections in 2008 meant the return of the first level electoral debates in Spain, after fifteen years of being paralyzed. These debates reactivated the holding of these television programs, since, since then, they have been organized in all general elections, that is, in 2011, 2015 and 2016. The question that arises here is the following: how did the debates between candidates for the presidency of Government held in 2008 influence the Spanish society? After fifteen years without electoral debates in general elections, this article analyzes the media impact and the implication in the decision of the vote of the face to face between José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (PSOE) and Mariano Rajoy (PP).

The effect produced by the electoral debates is an issue that has been the main object of study for the scientific community, after the first American debates of 1960. It should be noted here that there is an important diversity of factors affecting the decision of the vote such as: educational level, professional status, residence, purchasing power and also personal characteristics. But these factors, because they have little capacity for modification, have not been a strong point of analysis in political communication, which has rather focused on the study of the influence of variable factors, such as, for example, the information received by the voters and here the messages they receive through the electoral debate fully come into play.

Research has almost unanimously concluded that the electoral debates hardly modify the vote (Hagner & Rieselbach, 1978/1980, McLeod & Chafee, 1972). For example, one of the highest data of change of voting option recorded a 6% and occurred after the Nixon-Kennedy debate, according to the analysis by Roper (1960). In Spain, Díez Nicolás and Semetko (1995) concluded, after analyzing the first debates of 1993, that after the first González-Aznar debate, only 1% decided to vote, while 3% did so after seeing the second debate. On the influence of debates on the image of the candidate, there is a certain discrepancy between the authors Nimmo, Mansfield and Curry (1978/1980), who argue that debates do not alter the basic images of the candidates and, on the other hand, we find authors like Hagner and Rieselbach (1978/1980) who point out that the debates do influence the perception and the image the public forms about the candidates. Holding debates has an informative and pedagogical justification, since some studies show that debates are effective for the public to acquire knowledge. But, in this sense, there are also discrepancies, since when considering whether the debates serve the purpose of increasing the voter’s awareness of the issues and the positioning of the candidates, Becker and his colleagues (1978/1980) say yes, while Bishop, Oldendick and Tuchfarber (1978/1980) believe that this occurs only sometimes.

Rather, it seems that debates reinforce the political tendencies of the audience. Supporting this theory, researchers Hagner and Rieselbach (1978/1980, p.177) found out “that voters’ party identification, preference for a candidate, and evaluations of the candidate’s image have a significant impact on how the voter has seen the performance in the debate of each candidate”. Although the scientific consensus shows that debates reinforce the political positions of candidates, they can always influence those who are undecided. Before a competitive election, the quota of the undecided can mean victory, and the parties fight for it in the debates, without losing sight of their loyal voters. It must be borne in mind that, in order to succeed, a political party must mobilize its sympathizers and win a large number of the hesitant or undecided.

But, if debates hardly change the decision to vote, why do they worry politicians so much? It seems that a basic issue here is the fear of the “unexpected” that may occur on a live television set. We must bear in mind that, in a matter of policy, a “false” step can decide the outcome of the elections. This is produced by the asymmetric effect of the formation of the vote. Steeper (1980, p.81) points out that “the formation of a public image is an asymmetric process. While the positive side is built over a long period of time and involves many actions and successes, the negative side can be formed suddenly with a single action or statement.” Along the same lines, MacKuen and his colleagues (2007, p.136) maintain that voting can be changed when the emotional warning mechanisms are activated: “When they receive emotional stimuli for a reasoned consideration that is very disturbing with respect to the candidate of their party, citizens rely less on their predisposition and value information more.” But research in this regard has not yet solved the relationship between reason and emotion, since “there are very definite limits on what we can do today to increase the rationality of electoral behavior through a resource such as the electoral debate” (Bishop, et al., 1978/1980, p.196). It has also been found out that debates influence the public’s agenda, although the topics coincide more with the agenda of politicians and the media than with issues that interest citizens (Jackson-Beeck & Meadow, 1979).

What is evident is that electoral debates attract mass audiences. For example, the average audience of the successive electoral debates in the United States has been 60 million. In Spain, the debates held in 1993 between Aznar and González on Telecinco and Antena 3 became one of the most watched programs of the year, with an audience of more than nineteen million viewers, respectively. Every year, there are more countries with debates and when they are held, they attract large audiences, following the theory of Alan Schroeder (2014), debates are a “world trend” [1] .

In short, and according to Castells (2009, p.122), “televised political debates are less decisive than what is usually believed, they usually confirm the predispositions and opinions, which is why those who win debates usually win the elections: people usually bet on the winner as their preferred candidate instead of voting for the candidate that debated most persuasively.” On the other hand, Graber (1978/1980, p.119) warns that research on the influence of electoral debates should take precautions to prevent debates from being ascribed effects that have occurred during the process of holding the debate: the conditions of predebate, the very nature of the debates that, through their format and implementation, exists in the effects of the debate and, thirdly, the political climate in which the debate develops.

2. OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this article is to analyze the media impact and the influence on society of “face to face” debates between the main candidates for the presidency of Government in Spain during the general elections in 2008. For this purpose, we synthesized a summary of the scientific literature and the most significant studies on the development of political communication, as a discipline in which the study of electoral debates will be framed, reviewing the theories about the effects and influence of the media on society, the power of the media in politics and, specifically, in the development of the electoral campaign and the debates themselves.

As that this paper is carried out in the Spanish context, this study tries to approach the general political and media context in which the analyzed debates have been developed. In addition, it is intended to reflect the communication policy conducted by political parties and reflect their impact on the various social media and online.

3. METHODOLOGY

For the development of his piece of research, bibliographic, newspaper-consulting and documentary research, as well as the empirical observation of the electoral debates, have been used as scientific methods. So as to carry out this study, the material published in the national and international press was used, since this source is considered a reference also for other media.

In order to know the repercussion on the national media of the television programs we studied, the alerts compiled by TNS Sofres in the days before and after the debates at the request of the Television Academy have been reviewed. Specifically, more than 600 pieces of news and information about the debates in the national newspapers published from February 15 to March 17 have been analyzed.

In addition, information on television audiences provided by TNS Sofres has been considered, as well as the analyzes by Barlovento Comunicación and Corporación Multimedia consultancies, which issued specific reports on the analysis of audiences after the electoral debates.

The results of the pre-electoral and post-electoral surveys conducted by the Center for Sociological Research (CIS) have been taken as reference for the analysis of the influence of electoral debates. The documentation provided by the Academy of Television Sciences and Arts has been fundamental for this study, among which are the record of the media transmitting the debate and the documents of agreement between the political parties.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. The electoral campaign of 2008: Facing a technical tie between PSOE-PP

On January 14, 2008, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (PSOE) called the legislative elections that were held on March 9 and in which he faced, for the second time in a general election, Mariano Rajoy (PP). Thus an election campaign culminating in the electoral victory of the PSOE, although without an absolute majority, began. The previous legislature (2004-2008) began with the socialist victory after the attacks of 11-M and was marked from the beginning by a continuous tension between the two main political blocs, PSOE and PP. Throughout this period, the popular opposition harshly criticized the measures taken by the Socialists, raising issues of attack such as the theory of the conspiracy on March 11, the peace negotiations with the terrorist group ETA, the threat of the territorial break with the Estatut of Catalonia, the criticism against the subject “Education for the Citizenry” introduced in secondary education, and the positions against the new civic rights such as the law on homosexual marriage. These issues aroused social protests, which were supported and seconded by both the Popular Party and by similar means ideologically located in the central right, namely the newspaper El Mundo and the radio station COPE (González & Bouza, 2009, pp 232-236). The central topics of attack of the PP focused on the terrorism of ETA and the territorial unit, with the slogan “Spain is broken” (Mármol Lorenzo, 2013, p.17). At the end of this term and at the beginning of the elections, the economic crisis was incipient, but there was no concern among citizens about the future of the economy, since only to 15.9% it was very bad (CIS, 2008b). Therefore, although the popular party had identified this issue as relevant in the campaign, its catastrophic message did not impact with enough depth to alert society and promote a political change through this way. For its part, the Socialist Party began to use euphemisms such as “economic slowdown”, to downplay a crisis that would later take its toll, leading to Zapatero’s decision not to run again as a candidate for the presidency of Government.

The electoral campaign of 2008 was developed with a technical tie, with the Socialists having a slight advantage. In the pre-electoral macro-survey of the Center for Sociological Research (CIS, 2008b), carried out from January 21 to February 4, it showed that the socialists outperformed the popular ones with a forecast of 31% of the votes compared to 21.1%. By far, IU followed with 3.5%. On the other hand, Zapatero, as leader, ranked as the best rated candidate with 5.36 points. Meanwhile, Rajoy was left with 3.95. In the same survey, you can check the existence of a large number of undecided persons, just a little more than 20 days before the general election, since 30.1% had not defined their vote. Among the undecided, 38% considered choosing PP or PSOE and 8.3% would choose PSOE or IU. With these data, reinforced by the polls conducted from the press as Noxa Institute (La Vanguardia), Publiscopio (Público), DYM (ABC) or Metroscopia (El País), and according to the report published by La Gaceta de los Negocios (2008, February 18), it can be concluded that, in the elections of 2008, the data on intention to vote pointed to a virtual tie between the majority parties, PP and PSOE, with a slight inclination towards the Socialists. Given this electoral forecast, both candidates were willing to debate from the start (Campo Vidal, 2013, p.71).

In these general elections, political parties opted for campaigns fundamentally based on the figure of their candidate. The socialist strategists prepared a political communication campaign based on highlighting the positive aspects of their candidate as opposed to the character of Rajoy, whom they wanted to show as “a wet blanket” and “negative” (Sánchez, 2014, p.63). Thus, the Socialists posed a dichotomy between PSOE and PP, with the intention of mobilizing the votes of the left. From there, the design of a banner that showed photos of both representatives of the parties, in totally radical attitudes between positivity and negativity, under the slogan “It is not the same”, “in this line, the Department of Communication of the PSOE conceived the electoral debate as a possibility to develop this strategy of polarization” (Sánchez, 2014, p.63). For its part, the Popular Party, as the head of communications of the PP, Gabriel Elorriaga, acknowledged to the Financial Times, sought to demobilize the socialist vote, raising doubts about the economy, immigration and nationalist issues (Crawford, 2008, February 29) . In addition, the PP made an effort in this campaign to spread an image of Rajoy closer to citizens. They created a Rajoy website and a telephone was available so that citizens could make their proposals directly to the opposition candidate (Sánchez, 2014, page 62). However, it should be noted that, as far as the popular campaign is concerned, there was a breaking-off within the electoral committee due to the signing of an external consultant, Antonio Solá, which would bring about internal arguments about the campaign strategy. On the other hand, Izquierda Unida, with much fewer resources than the two main parties, would use the internet more actively as a communication platform with citizens and would develop new and alternative political marketing channels.

The Popular Party made an attempt to use the economic crisis as a campaign argument with a televised debate between Pedro Solbes (PSOE) and Manuel Pizarro (PP) on Antena 3 TV, but the economic debacle was so incipiently shown that the bad auguries of the popular party barely had any impact during the campaign. However, if something characterizes the election campaign of 2008, it was the holding of two face to face between José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and Mariano Rajoy as the main candidates for the presidency of Government, after fifteen years without any debates with these characteristics. So holding the debates undoubtedly became the high point of the electoral campaign and was received by the media and citizens with an important follow-up.

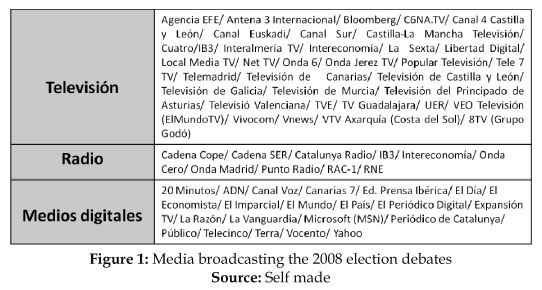

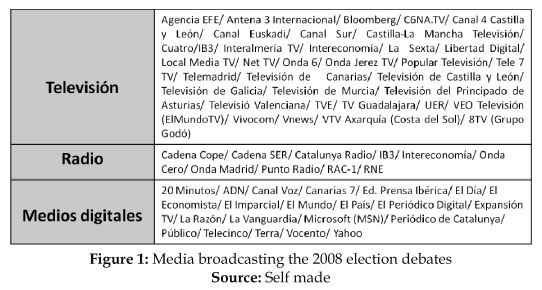

4.2. Media issuance and coverage of “face to face”

The institutional signal issued by the Television Academy was transmitted by all those media that requested it: national and international, regional, local (both by analogue and by Digital Terrestrial Television) television, radios and internet portals (among them the official websites of newspapers). The television broadcasts of the two debates achieved historical figures of follow-up on television in Spain and the debates of 2008 became the political programs with greater audience in the previous fifteen years. According to the analysis of Barlovento Comunicación, on the data of TNS Sofres, the first debate held on February 25, 2008 had an audience of 13,043,000 viewers with an audience of screen of 59.1%. Although, in the second debate more channels were added to the broadcast, the follow-up was somewhat smaller, since it lost more than a million average audience with respect to the first, accounting for 11,952,000 million viewers and 56.3% of the audience of screen, almost 3 percentage points less than the first debate. However, The opposite happened in the debates of 1993, since then the second debate accounted for more audience than the first, perhaps due to the surprising effect of the defeat of Felipe González against an inexperienced José María Aznar. In 2008, La 1 de Televisión Española was the channel with the highest audience in both debates, followed by Cuatro and La Sexta. The debates were also broadcast online. The first debate got 398,548 video requests and 144,666 unique users, and the second recorded 217,107 video requests, with 87,034 unique users. In the second debate, an improvement was made: the sign language broadcast, which was also offered on the internet and was followed by 1.3% of the total audience that connected with the debate through this way. To these data we must add the audience in several DTT channels, on radio broadcasting and network stations that are not counted by TNS Sofres. According to the registry the Television Academy made of the sum of the two debates, in total 30 television channels, 10 radio stations and 21 internet portals contracted the broadcasting services of the institution signal.

The debates had a great media impact, only in the national media, from February 15 to March 17, more than 600 pieces of news and information about the debates were published in national newspapers and there were 371 appearances on the radio and 372 on television, from February 13 to March 15. It is also worth mentioning the repercussion through the internet. According to a study published on May 7, 2008, Google had recorded more than 84,000 mentions related to the debates between Rajoy and Zapatero and the moderators. On YouTube, more than 625 videos were counted, adding up to a total of 120,000 visits.

The return of debates in Spain also had an important impact on the international media, turning Spanish debates into a global event. From Spain, the signal was offered abroad through the channels of Televisión Española Internacional (which broadcasts to Europe, Africa and the western part of Asia, South America and Eastern Coast of North and Central America, countries of the Western Zone of North and Central America, Central and Eastern Asia, and Oceania) and Antena 3 Internacional, with a significant presence in Iberian-America, the United States and the Caribbean. In the second debate, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) joined the broadcast, the network of which is made up of television and radio in more than 55 countries throughout Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Thus, through this signal, the program could be followed in countries such as Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Switzerland or Morocco, among others. It is worth mentioning the international dissemination work carried out by agencies such as Notimex, Associated Press, Reuters or France Press, the teletypes of which had a great impact on the international media, and the specific coverage by special envoys from the United Kingdom, Portugal, the Maghreb countries, United States and Latin America.

4.3. Who won the debate?: “My candidate”

After the broadcast of each debate, the media began their particular debate on the debate, in which they point out the result of the debate, assigning winner, loser or tie. After the debates, the media reflected the analyses, interpretations, polls and opinions of what happened on the set. The media offered different versions, so much that the sum of the partisan interpretations of the media could not specify a clear and unanimous winner. The radio and television channels were the first to take stock of the debate in their analysis programs after its broadcast. In these gatherings, they normally included representatives of political parties, as with the case of La 1 TVE program 59 segundos, and each “attributed the victory of debate to himself” (Altántico, 2008, February 27). The discourse of the parties was repeated in the press: “The PSOE said that José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero” has long won to “Mariano Rajoy in his first debate” and “The PP says that Mariano Rajoy garnered a “resounding victory” tonight on his face to face with Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero” (Granada Hoy, 2008, February 26). The parties that were left claimed their presence in the press, on the part of Izquierda Unida, “Gaspar Llamazares discredited the debates between the two candidates of the main parties because they are a ‘privatization of politics’ and limit ‘plural participation’ since they prevent the third national force from presenting its proposals “(Europa Press, 2008, February 26).

The day after the first debate, on February 25, 2008, the verdict of the media came based on their own polls. Although most of the polls pointed to Zapatero as the winner of the first debate, the media did not agree on the report. The newspaper El Pais considered the socialist candidate to be the winner, with the headline “Victory to the points of Zapatero” and with the publication of the poll by Metroscopia reflecting that 46% of the population believed Zapatero had won and 42% thought Rajoy had won. A very clarifying fact about the polls has to do with the sympathy towards the party. Thus, according to this study, “84% of the respondents who declared themselves to be voters of the PP considered Rajoy to have won, so did 74% of the PSOE voters about Zapatero” (El País, 2008, February 26). The newspaper Público echoed the poll by El Periódico, in which Zapatero extended to 5.5 points his advantage over Rajoy after the first face to face (EFE, 2008, February 28). Meanwhile, the newspaper ABC offered a very different version with the headline “Rajoy wins to Zapatero by 5-3” (Calleja, 2008, February 27). In a more moderate but pro Rajoy line, the newspaper El Mundo would be in favor of the performance of the popular candidate, with the headline: “A Rajoy always on the attack forces Zapatero to hide behind the past” (Cruz, 2008b, February 26). The paper was based on surveys conducted by El Mundo-Sigma Two, which considered Zapatero to be the winner with 45.5% and Mariano Rajoy with 42%. This information was published under the headline: “Zapatero won by the minimum but convinced his partisans less than Rajoy” (El Mundo, 2008, February 26). And this newspaper also made an interpretation of these data: “It was expected: in this type of polls, the PP leader is only voted by his own followers, while the PSOE drags, in addition to its supporters, virtually all other parties “(Cruz, 2008a, February 26). Complementing this information, the survey the newspaper had conducted among readers of its website was also published, the result indicated that “57% of voters of elmundo.es consider Rajoy to be the winner and 43% think it is Zapatero” (El Mundo, 2008, February 26). In the same vein, Expansión titled “Rajoy attacks with the economy and Zapatero returns to 11-M” (Mazo, 2008, February 26). The Economist coincided with the approach “The economy Cornering Zapatero” (Pastor & Toribio, 2008, February 26). ADN, meanwhile, prayed: “Rajoy gets the key to the debate” (Caballero, 2008, February 26). The websites of newspapers also conducted their own surveys on the outcome of the debates with very different results. Although the telephone polls had resulted in Zapatero being the winner, in the polls through the network there were discrepancies, since “their opinion reflected the ideological trend of the website they had used to follow the debate, since these websites belonged to the main newspapers, often with well-defined political tendencies” (Castells, 2009, p.313). Thus, while the opinions of Internet users in El Mundo or ABC were favorable to Rajoy, in those in El País or the chain SER, Zapatero won.

The leader of the PP won in the websites of El Mundo and ABC, while Zapatero won in El País and Cadena SER as well as in La Vanguardia, El Periodico, Público, 20 Minutos and ADn. In El Mundo, Rajoy won the debate with an advantage of 14 points (57% vs. 43% for Zapatero), while in abc.es, with 10,000 votes, the advantage was only 3.6 points (51.8 % versus 48.2 percent). The website that resulted in a greater difference in favor of the Socialist Party was that of Público (78 percent versus only 18% for Rajoy). (EFE, 2008, February 26)

The regional press, mostly nourished by the information agencies, remained more neutral regarding its verdict on the debate, repeating the communiqués such as that of the EFE news agency (2008, February 26), which published, “Zapatero and Rajoy lead a full debate of reproaches.” Thus, in the regional press, one can find the following approaches: “Zapatero and Rajoy are the winners of a tight and intense debate” (La Región, 2008, February 26); or “Zapatero and Rajoy maintains a tense debate with harsh reproaches about ETA and immigration” (Atlántico, 2008, February 26); or “Zapatero and Rajoy accuse each other of lying and causing trouble.” (Granada Hoy, 2008, February 26). The television broadcasting stations would also conduct their own polls on the outcome of the debates. The survey of TNS Demoscopia para Antena 3 TV, Zapatero wins with 45.4% against 39.3% for Rajoy. This same poll reflected that Zapatero won in Andalusia and Catalonia, while Rajoy did it in Valencia; the poll of the Opina para Cuatro Institute pointed out that 45.4% of Spaniards believed that Zapatero had won, compared to 33.4% who saw the popular leader as the winner; the poll of Invymarkse Institute for Research and Marketing for La Sexta announced that 44.7% of viewers said that Zapatero won the debate, while 30.1% thought that the winner was Mariano Rajoy.

In the second debate, the same dynamic was repeated in the polls and opinions of the media. Of course, in their public statements, “the leaders regard themselves as winners... again” (La Región, 2008, March 4) but, in general, the polls were inclined to go for Zapatero. The newspaper El Público titled: “Zapatero returns this time the blows of Rajoy” (F. Garea, 2008, March 4); and in the same line, 20 minutos pointed out that “Zapatero wins three rounds and Rajoy two” (Escuedier, 2008, March 4). The polls conducted by Sigma Dos for El Mundo showed that Zapatero was the winner with 49% against 40.2% for Rajoy. However, La Razón published that “Rajoy beats a Zapatero shielded in promises” (Martinez, 2008, March 4). Regarding television, Instituto Opina para Cuatro reflects 50.8% for Zapatero and 29% for Rajoy; and Invymarkse Institute for La Sexta, 49.2% for Zapatero compared to 29.8% for Rajoy. Meanwhile, Antena 3 TV conducted no polls after the second debate (20 Minutos, 2008, March 4).

4.4. Who won the debate?: “My candidate”

The ability to influence the results of the vote is always an object for discussion. The post-election survey by the Sociological Research Center (CIS, 2008a) collects relevant data to this piece of research with respect to the influence of Spanish citizens in debates. 58.2% admitted having seen the two debates wholly or in part; only 9.2% saw the first debate wholly or in part; only 3.1% saw the second debate wholly or in part, 21% did not see them but had references from them and 7.3% neither saw nor had any references from them. Of those respondents who followed the debates, 53.3% felt that Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero was more convincing, while 21.5% believed so concerning Mariano Rajoy. For 6.9%, the two were equally convincing and 15.8% thought that neither of them did it.

The study by CIS also revealed in what sense the debates were taken into account when voting. 63.5% said that the discussions had no effect at all when voting; for 18,6% the debates reinforced their decision to vote for the party they had thought; 7.3% were encouraged to vote; 3.9% were helped to decide who to vote for and 1.8% were encouraged to abstain.

From this study, we draw an interesting reading: in the polls about who had won the debate, Zapatero wins and, also, very few recognized to have changed their vote after viewing them. However, a not inconsiderable percentage was encouraged to vote or decide on one or the other party. “Sometimes a little change among the decided voters or among those thinking to abstain or among some undecided voters can be decisive to tip the balance on one side or the other” (Santamaría, 2009, p. 129). Increased participation is critical because it always changes the result because it alters the distribution of seats. To a significant percentage, the debates reinforced their decision to vote, which according to statements by José María Canel to the press, it is “an important effect if you consider that the PP has a voting floor fairly fixed that it should care for, the PSOE will seek, through its volatile vote, to strengthen the decision of those it managed to win in 2004” (Martín-Aragón, 2008, February 26). If the study by CIS shows the debates have limited ability to influence voting, they demonstrate their usefulness to arouse interest in the political information of citizens, as they were followed up very much as a basis of the progress of democracy. For authors like Santamaría (2009, p. 129), discussions become a key institution to the democratic system because they provide citizens with firsthand information about the personality of the candidates and their ability to solve conflicts and their communicative ability, they familiarize the audience with the leaders of the two main political parties and induce interest in politics. The PP negotiator concluded the issue this way:

But, ultimately, beyond any other consideration, the real challenge should be the provision of sufficient evidence so that citizens can reasonably support the reasons for their choice and thus stimulate, to the greatest possible extent, their active election participation. To this task, and not to other, public election debates between candidates should actually serve. Let us trust it will be this way in the future, as this will ultimately lead to the benefit of all that which, beyond their ideological preferences, interests everyone: the development and progress of our democratic system. (García-Escudero Márquez, 2009, p. 27)

The debates of 2008 had another important effect, an attempt to regulation which finally did not become effective. After these debates and when he was already in the Government, the Minister of Public Works and negotiator of PSOE in the debates, José Blanco, proposed a law to collect the obligation to conduct discussions to avoid the game of challenges, which he called “sterile”, which took place in each campaign on the occasion of holding the debates. Blanco justified his proposal this way:

In the 2008 elections, we have taken a big step in the right direction. But I am convinced that no political agreement on this matter will be lastingly effective until the sovereign people do not impose the debates as a common and unavoidable fact for any candidate. Until it is clear to everyone that leaving the chair empty will never be profitable. (White, 2009, p. 34).

Finally, the outcome of the 2008 general elections, held on March 9, was a victory for the PSOE of Rodríguez Zapatero with 11,289,335 votes (43.87% of all voters) against 10,278,010 votes for the Popular party, which accounted for 39.94%. With participation of 75.32% (in 2004, it was 77.21%, a very high figure caused by the mobilization of the left following the attacks of 11-M), these results enabled the PSOE to obtain 169 deputies (five more than in the previous general election). The Popular Party also increased its representation in Congress with five deputies more than in 2004, reaching 154.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The media, both national and international, agreed on the importance of the return of election debates in Spain, after not been held in the last fifteen years. The press described the debate as tense and the polls by television christened Zapatero as the winner of the first dialectic contest, although both leaders declared themselves winners in subsequent statements to the media. However, although most surveys resulted in Zapatero being the winner, the media agreed on the verdict to declare a clear and unanimous winner. The media connected to the left such as El País as well as the polls conducted by Cuatro and La Sexta, even Antena 3 TV, pointed to Zapatero as the winner, while the media linked to the right such as ABC, El Mundo and La Razón positioned themselves more in favor of Rajoy as the winner. The regional press, fed largely by agencies, remained neutral in their opinion. Meanwhile, both political parties made statements after the debates, claiming that they had clearly triumphed over the other.

The ability of the electoral debates to influence the voting intention has always been the subject of academic discussion. Regarding the 2008 election debates, it seems that the guidelines agreed by the scientific community about the possible effects are repeated. Taking CIS post-election survey as reference, it can be concluded that the discussions had limited influence on the decision to vote, since only 3.9% of the population decided to vote after seeing them. A relevant fact indicates that the debates prompted 7.3% to vote, while they encouraged 1.8% to abstain. The elections recorded a final participation of 75.32%, a figure slightly lower than in the previous general election in 2004, when 77.21% of the population participated. The high percentage of votes in 2004 reflects the significant mobilization of the leftist voting after the attacks of 11-M. So we can conclude that, although the 2008 debates did not serve just to change the vote, they did mitigate abstention. This is important because greater participation always changes the result, because it alters the distribution of seats. These small figures can be decisive to political parties that are facing a technical dead heat. What the studies and analyses of audiences after the debates do demonstrate is the ability to call that television programs had and the interest in political information they aroused in the citizenry. Finally, in the general elections, the PSOE won with 43% against the PP with 39.94% of the total, which came to consolidate the Socialists in power after their disputed victory in 2004. These election results will also give continuity to bipartisanship in the Spanish political model, which it will keep in the elections in 2011 and begin to crack in the general election in 2015, with the emergence of new political parties.

REFERENCES

1. Barreiro B, Sánchez-Cuenca I (1998). Análisis del cambio de voto hacia el PSOE en las Elecciones de 1993. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 82, 191-211.

2. Becker LB, Sobowale IA, Cobbey RE, Eyal CH (1978/1980). Debates “Effects on Voters” Understanding of Candidates and Issues, en Bishop GF, Jackson-Beek M, Meadow R (Eds.). The Presidential Debates: Media, Electoral, and Policy Perspectives (pp. 126-139). New York: Praeger.

3. Bishop GF, Oldendick RW, Tuchfarber AJ (1978/1980). The Presidential Debates as a Device for Increasing the Rationality of Electoral Behavior, en Bishop GF, Jackson-Beek M, Meadow R (Eds.). The Presidential Debates: Media, Electoral, and Policy Perspectives (pp. 179-196). New York: Praeger.

4. Blanco J (2009). Dejar la silla vacía nunca más será rentable, en Gallego-Reguera M (Ed.). El debate de los Debates: España y EE. UU. 2008 (pp. 29-34). Barcelona: Àmbit.

5. Bustamante E (2013). Historia de la radio y la televisión en España: Una asignatura pendiente de la democracia. Barcelona: Editorial Gedisa.

6. Campo-Vidal M (2013). La cara oculta de los debates electorales: Los debates cara a cara presidenciales en España. Madrid: Instituto de Comunicación Empresarial (ICE) y Nautebook.

7. Castells M (2009). Comunicación y poder. Madrid: Alianza.

8. CIS (2008). Preelectoral Elecciones generales y al Parlamento de Andalucía (Estudio Núm. 2.750. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

9. Díez-Nicolás J, Semetko HA (1995). La televisión y las elecciones de 1993, en Swanson DL, Muñoz-Alonso A, Rospir Zabala JI (Eds.). Comunicación política. Madrid: Universitas.

10. García-Escudero-Márquez P (2009). Debates electorales para más democracia, Gallego-Reguera M (Ed.). El debate de los Debates 2008: España y EE. UU. (pp. 23-27). Barcelona: Àmbit.

11. González JJ., Bouza F (2009). Las razones de voto en la España democrática (1997-2008). Madrid: Catarata.

12. Graber DA (1978/1980). Problems in Measuring Audience Effects of the 1976 Debates, en Bishop GF, Jackson-Beek M, Meadow R (Eds.). The Presidential Debates: Media, Electoral, and Policy Perspectives (pp. 105-125). New York: Praeger.

13. Hagner PR, Rieselbach LN (1978/1980). The Impact of the 1976 Presidential Debates: Conversion or Reinforcement?, en Bishop GF, Jackson-Beek M, Meadow R (Eds.). The Presidential Debates: Media, Electoral, and Policy Perspectives (pp. 157-178). New York: Praeger

14. Jackson-Beeck M, Meadow RG (1979). The Triple Agenda of Presidential Debates. Public Opinion Quarterly, 43, 173-180.

15. Mármol-Lorenzo I (2013). Las elecciones generales de 2008: Las estrategias de competición, Crespo I (Ed.). Partidos, medios y electores en procesos de cambio (pp. 17-31). Valencia: Tirant Humanidades.

16. Mckuen M, Marcus GE, Neuman WR, Keele L (2007). The Third Way, the Theory of Affective Intelligence and American Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

17. Nimmo D, Mansfield M, Curry J (1978/1980). Persistence and Change in Candidate Images. en Bishop GF, Jackson-Beek M, Meadow R (Eds.). The Presidential Debates: Media, Electoral, and Policy Perspectives (pp. 140-156). New York: Praeger.

18. Roper E (1960). Polling Post– Morten, Saturday Review, Noviembre, 10-13.

19. Ruiz-Contreras M (2007). La imagen de los partidos políticos: El comportamiento electoral en España durante las elecciones generales de 1993 y 1996. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

20. Sánchez R (2014). El control audiovisual de las campañas electorales. Madrid: Editorial Fragua.

21. Santamaría J (2009). Visión comparativa con Estados Unidos, en Gallego-Reguera M (Ed.). El debate de los debates 2008: España y EE. UU. (pp. 125-129). Barcelona: Àmbit.

22. Steeper FT (1980). Public Response to Gerald Ford’s Statements on Eastern Europe in the Second Debate. en Bishop GF, Jackson-Beek M, Meadow R (Eds.). The Presidential Debates: Media, Electoral, and Policy Perspectives (pp. 81-101), New York: Praeger.

23. Vidal-Riera F (1997). Los debates “cara a cara”: Fundamentos básicos para la celebración de debates electorales audiovisuales entre los líderes de los partidos mayoritarios. Tesis de Doctorado). Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid.