doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.147.41-64

RESEARCH

WOMEN IN THE REPUBLICAN ANTICLERICAL IDEOLOGY. A STUDY FROM THE MALAGA PRESS

LA MUJER EN LA IDEOLOGÍA ANTICLERICAL REPUBLICANA. UN ESTUDIO DESDE LA PRENSA MALAGUEÑA

A MULHER NA IDEOLOGIA ANTICLERICAL REPUBLICANA. UM ESTUDO DA IMPRENSA MALAGUENHA

Israel-David Medina-Ruiz1

Licenciado en Historia, graduado en Magisterio, máster en Educación y doctorando del programa de doctorado Estudios Avanzados en Humanidades, en la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Málaga, de cuyos resultados, en parte, se presentan en este artículo

Antonio-Rafael Fernández-Paradas2

1 Malaga University. Spain

2 Granada University. Spain

ABSTRACT

The process of social laicization undergone in Spain since the early twentieth century led to active political anticlericalism that meant a change in a broad sector of the population. Although Spanish republicanism has traditionally been anticlerical, as the third decade approached, its postulates would be increasingly vehement. The objective we want to achieve with this piece of research is to make women visible during this historical period and under this concrete ideology, in order to know the position of anticlericalism regarding the incipient feminism and the beginning of the departure of women from the family. To this end, we have used a qualitative methodology that has allowed us to analyze exhaustively the republican press in Malaga as the main source of study. This source will provide us with important information to understand both the situation of women and men, since men will have their misgivings and fears about the new role that women are acquiring. A woman traditionally silenced, with no options beyond the private sphere of home, but who also in this first third of the century will undergo an awakening and a beginning of the struggle for their rights, as we will see, and not just taking into account their imposed duties according to the “natural law” that is proper to them. An anticlerical republicanism that will have a clear position on the role and function of women social beings.

KEY WORDS: anticlericalism, woman, laicism, politics, press, II Republic, Malaga

RESUMEN

El proceso de laicización social experimentado en España desde principios del siglo XX conllevó un anticlericalismo político activo que supuso un cambio en un amplio sector de la población. Si bien el republicanismo español ha sido tradicionalmente anticlerical, conforme se acercaba el tercer decenio sus postulados iban a ser cada vez más vehementes. El objetivo que queremos conseguir con esta investigación es visibilizar a la mujer durante este periodo histórico y bajo esta ideología concreta, para así conocer la postura del anticlericalismo en cuanto al incipiente feminismo y el comienzo de la salida de la mujer del ámbito familiar. Para tal fin hemos utilizado una metodología cualitativa que nos ha permitido analizar de forma exhaustiva la prensa republicana malagueña como fuente principal de estudio. Esta fuente nos va a proporcionar datos importantes para comprender tanto la situación de la mujer como la del hombre, ya que este va a tener sus recelos y sus miedos ante el nuevo rol que está adquiriendo la mujer. Una mujer tradicionalmente silenciada, sin opciones más allá de la esfera privada del hogar, pero que también en este primer tercio de siglo va a experimentar un despertar y un comienzo de la lucha por sus derechos, como veremos, y no solo atendiendo a sus impuestos deberes a tenor de la “ley natural” que le es propia. Un republicanismo anticlerical que va a tener un posicionamiento claro sobre el papel y la función de la mujer como ser social.

PALABRAS CLAVE: anticlericalismo, mujer, laicismo, política, prensa, II República, Málaga

RESUME

O processo de laicização social experimentado na Espanha desde princípios do século XX implicou um anticlericalismo político ativo que supôs uma mudança em um amplo setor da população. Se bem que o republicanismo espanhol foi tradicionalmente anticlerical, conforme chegava o terceiro decênio seus postulados iam ser cada vez mais veementes. O objetivo que queremos conseguir com esta investigação é visibilizar à mulher durante este período histórico e sob esta ideologia concreta, para assim conhecer a postura do anticlericalismo em relação ao incipiente feminismo e o começo da saída da mulher do âmbito familiar. Para esta finalidade utilizamos uma metodologia qualitativa que nos permitiu analisar de forma exaustiva a imprensa republicana malaguenha como fonte principal de estudo. Esta fonte nos proporciona dados importantes para compreender tanto a situação da mulher como a do homem, já que este terá suas desconfianças e medos diante do novo papel adquirido pela mulher. Uma mulher tradicional silenciada, sem opções nada mais que na vida privada do lar, mas que também neste primeiro terço de século vai experimentar um despertar e um começo da luta por seus direitos, como veremos, e não somente atendendo a seus deveres impostos. Um republicanismo anticlerical que terá um posicionamento claro sobre o papel e a função da mulher como um ser social.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: anticlericalismo, mulher, laicismo, política, imprensa, II República, Málaga

Correspondencia: Israel David Medina Ruiz. Malaga University. Spain.

israelmedina@uma.es

Antonio Rafael Fernández Paradas. : Granada University. Spain.

antonioparadas@ugr.es

Received: 18/10/2018

Accepted: 11/03/2019

Published: 15/06/2019

How to cite the article: Medina Ruiz, I. D., and Fernández Paradas, A. R. (2019). Women in the republican anticlerical ideology. A study from the Malaga press. [La mujer en la ideología anticlerical republicana. Un estudio desde la prensa malagueña]. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 147, 41-64. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2019.147.41-64 Recovered from http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1135

1. INTRODUCTION

The resurgence of anticlericalism in Spain during the first decade of the twentieth century had obeyed the interests of the Republican parties within the context of the Spanish-American War of 1898 and the consequent search for the culprits of the decline of Spain (Cueva, 1998, p. 213). As pointed out by Suárez (2014, p. 167), after the crisis of 98, anticlericalism reappeared “as one of the most striking elements of the new political situation.” An accumulation of factors both internal (as, for example, the policy initiated by José Canalejas), and external (in which we can indicate the French religious policy), were those that contributed to place the religious question at the center of political life Spanish, especially with regard to religious orders. This fact was not surprising since it was motivated by the anticlerical policy of the French governments, which with Waldeck Rousseau (Cueva, 1997, p. 103) and his Law of Associations, caused the prohibition of any religious association and, consequently, religious people from France came to Spain. This generated an entire political and educational event that accentuated the anticlerical sensitivity in Spanish politics.

There is no doubt that this laicist and secularist French policy that breaks the relationship between Church and State will be the trigger to bring Spanish liberal and republican secularism to a new dimension. Indeed, Spanish society experienced much progress in secularization at the beginning of the 20th century, showing it as social dechristianization and political anticlericalism (Requena, 2002, p. 40). We thus passed to a dichotomous discourse between tradition and modernity, in which the republicans proclaimed themselves the champions of modern values in the face of a tradition of obscurantism, related to the monarchy, which came from the hand of the Catholic Church as a necessary endorsement (Suárez, 2000, pp. 186-187). This discourse will cause the religious question to become a national problem, increasing the conflict to the forefront of public life, anticlericalism becoming a mass, popular and compact movement (Revuelta, 1991, demanding the withdrawal of religion to the private sphere and the total separation of the State with the Second Republic.

In the middle of this context appears a figure of great importance, although not yet being sufficiently treated historiographically, the woman. Women have an important weight within society and within this dichotomy clericalism - anticlericalism that we have raised, despite the fact that, in their vast majority, women continue to develop a passive and discriminated role in the role of wife and mother (Rivas, 2013, p. 352) to which they are relegated to perpetuity. This continues to happen at the beginning of the decade of the 30s. But with the arrival of the Second Republic, we witnessed a series of initiatives that, although punctual, are a beginning of change for the development of a feminism that seeks to give women the place they deserve within society on an equal footing with men.

2. OBJECTIVES

So as to shed light on the image and the concept of women that people had during the Second Republic, from a republican anticlerical perspective, we focused on the exhaustive analysis of the republican press in Malaga, among other sources. The main objective that we intend to achieve is to make visible how women were, from a socio-political point of view, during this period of time. For this purpose we hope to:

3. METHODOLOGY

For this piece of research, we have selected a mainly qualitative methodology because it can respond better to how and what: how did the republican anticlerical press react to a greater political-social presence of women during the Second Republic? And what was the concept of women in general from the particular anticlerical vision? All this through qualitative techniques that, as indicated by Alía (2008, p. 45), will contribute to the search for and observation of a specific documentation.

The press, as a historical source, provides us with data of unquestionable value for the study of anticlericalism in Spain. Some data that could hardly be collected from other types of sources because, although already since the beginning of the 20th century, the Malaga press will be gaining rigor by becoming an informative press (Galindo, 1999, pp. 20-22), opinion articles are still present; and, thanks to them, we will be able to analyze the ideology that emanates from their words, facts and statements on certain issues over time.

For this purpose, we have used the historical press stocks belonging to the newspaper and periodicals library of the Municipal Archive of Malaga and the Narciso Díaz de Escovar Archive. Of all of them we have selected those referring to the republican press that will have a presence during the study period. Next, we will detail it:

In the same way, we have handled secondary sources, making a bibliographical analysis pertinent to the subject, so that it offers us more information about general or concrete aspects that could not be elucidated with the primary sources. Serving, in fact, in some cases to give value to them.

4. DISCUSSION

Although the current of democratic thought defended feminine demands, the republican parties showed, in fact, a limited interest in these questions (Díez, 1995, p. 27). Despite this, women, considered the weaker sex in the patriarchal ideology of the time, progress slowly but surely and firmly towards leveling with the male sex during the first third of the 20th century.

Women, who used to be like slaves for men, now men are the ones who are in danger of being so for women, as is argued in these republican media, because women during the Second Republic are no longer the submissive, the quiet being of other times, but they are the coquettes, “who sometimes comes to prevail with her spouse the husband, who has to resign himself to endure it with great inner disgust and always trying to never get to violence, because this would bring nothing more than ruins and misfortunes” (1) to the whole family.

From this view, it is argued that it is since 1915 when the starting point of the career of women towards their leveling with the male sex is set, and this is due to the fact that the Great War or European war took place at that time. A war that caused the collapse of the strongest powers, all of them impoverishing, hunger and misery lavishing in these territories. It is from here that “the weak arms of women began to work” (2) and feminism began. A feminism conceived, according to the republicans, as the access of women to work of all kinds that, although it seemed contradictory, women would perform in the same way as men, tilling the land, in desks, offices, factories, warehouses, etc.; that is, in a high number of different occupations traditionally performed by the male. It is a reality that republican and left-wing sectors recognize the fact that women have come to occupy high positions in the police and in other jobs, such as that occupied by Victoria Kent, who currently holds the position of Director General of Prisons.

However, this recognition of women’s labor development does not mean that they are in women’s favor totally without making objections. One of the most harsh and redundant criticisms in the thinking of the republican media is the existence of an infinity of men who, due to lack of work, are in poverty, emphasizing that this situation is directly due to the appointment of women to positions that should be held by men.

This tendency to incorporate women in the workplace also raised questions about why most business owners, managers and other entrepreneurs asked women to work in their businesses instead of turning to men. And this despite the fact that these women had no previous experience in the position to be held neither did they really know how to perform a certain trade, as compared to men who did have experience and were prepared for the position in question. The explanation to this paradox, interesting for the working class, especially males, was given alleging that it was due to the miserable salary paid by employers and business owners to women, lower salaries for a labor force than, in the end, would have a performance equal or similar to that of men. This “bargain” for the entrepreneurs caused the work of men to be despised when they, after World War I, could begin to join work.

It is for all this that, along with the development of the middle classes in Spain during the 20s and 30s (Beasgoechea Gangoiti & Otero Carvajal, 2015) and, especially, during the Second Republic, this promotion of women to work was seen as a problem for men and social stability. Not seeing this feminine work as something positive but as a “robbery to the work of their husbands”, thus creating “important damages in the interests of the fatherland” (3). Moreover, they go too far in accusations against women who, having to return to their domestic chores, clinging to motherhood and marriage as something consubstantial to their being women, instead they continue to seek their freedom beyond the domestic sphere. That is why they expose the development of a feminism that is “transcending the limits of the natural”, in such a way that

instead of being only the help of man, the substitution of him in the precise cases or required by the various situations engendered by the march of society, she threatens to be the dominator in everything, while now she every day changes and multiplies her rights more neatly, in such a way that soon, as in other nations, she will begin to prostitute his honor (4).

There is no stance in the republican and anticlerical ranks in favor of women having freedom, but a nuanced freedom, a freedom that in no case should be equal to that of man, a freedom that is relegated to the household sphere. That is, they accept the demands of women, they accept to hear the voice of women with justice, equaling them to men, but in everything that “does not oppose her nature” (5) because the important thing is “to prepare her properly to carry out her triple mission: as a woman, mother and wife, and social being” (6).

From these newspapers related to the left, the thought of how women should be and act is still traditional, typical of patriarchal systems where women are relegated to obedience and submission to men. Here we present an example of this, published in 1933 in El Popular; it is an article in the women’s section where the following advice is given to single women (7):

And all this is so because the man, before this woman who starts to be a feminist and to fight for their social rights, for equality with men, seeking the same freedoms as him, makes that, in his dignity as a man, the very “Law of Nature forces him to repulse” (8). It is curious how they argue that women, if reaching that desired equality, what will achieve is to destroy and eliminate all the charms of home, because “as the woman becomes masculine, the man becomes effeminate” (9) This is so, as they argue, because, as women are taking a fancy to work, they flee from marriage, their former slavery, causing men to experience aversion to work and to come closer to marriage.

(1) Municipal Archive of Malaga (hereinafter AMM). The Popular, November 5, 1931, p. 1.

(2) AMM. El Popular, October 27, 1931, p. 2.

(3) AMM. El Popular, December 05, 1931, p. 1.

(4) AMM. El Popular, October 27, 1931, p. 2.

5) In this vision of woman, linked to the concepts of wife and mother, a sphere of her own is created that circumscribes what is suitable for her, what is natural to her being. As Ramos (1993, p.82) points out, the jobs related to this natural function of women would be limited, basically, to teachers, nurses, social workers or seamstresses. Otherwise, it would go against nature and attack man by entering a sphere that is not his own.

(6) AMM. El Popular, October 2, 1931, p. 8.

(7) AMM. El Popular , April 16, 1933, p. 12.

(8) AMM. Amanecer, October 3, 1931, p. 12.

(9) AMM. El Popular, October 27, 1931, p. 2.

4.1. Women and the right to vote. A vision before the elections of 1933

With the arrival of the Second Republic, one of the measures adopted regarding women was the right to vote. On December 1, 1931, at seven thirty in the afternoon, in a tight vote of 131 votes against 127, women’s suffrage was granted.

This fact provoked an extensive number of articles in anticlerical media because they saw in it a danger to the Republic, the newspaper Amanecer (10) being one of those who strongly opposed the female vote. That is why we can ask the reasons for this fear of women’s access to vote by the republican and anticlerical media. The answer is found in the conception anticlericalism had of women as the depository of the Catholic faith that lived in a constant influx of the church and, especially, of her confessor, who exerted control over issues related to privacy of home. In fact, the ideal field of penetration of Jesuit preaching and Catholic religiosity in this era will be women, especially in high society, imposing in homes the dictatorship of a religion of appearance (De Mateo, 1987, p. 94).

Therefore, the anticlerical sectors did not like the approval of this decree, thinking that it was a bad step for the Republic because, precisely, women have been granted the instrument that is going to give them the revenge of which they dream (11) not only the woman to counteract the attack suffered since the advent of the Republic to the Church, with the burning of convents in May 1931 and the other provisions on Church-State separation and secularization of society; but the Church and the right have been granted the use of this measure against the Republic itself, women being instructed and guided in this matter as the necessary accomplices at the service of social oppression and clerical ideology.

To the anti-clerical left, women’s suffrage in countries with a Catholic tradition, such as Spain, is a weapon that only reactionary extremists can use effectively and profitably. They use as an argument that, when the president of the Union of French Women asked the president of the Council of Ministers of France, Henry Poincaré, about why he opposed the French women having an electoral vote, she got the following answer, “that the naive and stunned Spanish Republicans: should meditate much because they want France to remain a secular republic” (12) This would be the reason why France had been a Republic for 60 years, even though the culture of French women was incomparably superior to that of Spanish women.

Precisely the issue of the lack of culture of Spanish women is recurrent in the anticlerical ideology. We see how anti-clerical media such as El Popular talk about the education of women, focusing on their lack of it and their illiteracy. Certainly, illiteracy at that time was high and, especially, in the case of women it was more accentuated. In 1930, 24% of the male population was illiterate, as compared to 40% of the female population, almost double illiteracy in the female sphere (Vilanova and Moreno, 1990, p. 22). That is why they argue that this Spanish woman who “has not yet learned to reason is a danger to have her issue her political reason through voting” (13), because, as they indicate, it is precisely this cultivated ignorance the one that clericalism uses to abuse its faith in all areas (14). In such a way that the “Spanish woman is even more devoted to the priest than to her husband” (15) especially in everything related to what is within the sphere of thought, relegating to the background the influence of the husband. All this motivated precisely by her lack of culture and the fact that she is alien to electoral issues, causing her vote to be assigned to the will of her husband, her boyfriend or, especially, to what the priest stipulates (16). Therefore, we see how they describe an illiterate woman who only acts under the guidelines imposed by religion, because, as these anticlericals say, women in Spain

no longer go out of their house because they cannot call going out to cross the street or the square and immerse themselves in the parish, in the cathedral or in the chapel where they proselytize the free will of thought at the feet of a priest or a friar, who fit in the chromatic scale that includes from Zuloaga to Vázquez Díaz (17).

From the anticlericalism, they assert that the Spanish woman is fundamentally Catholic and, as such, cannot forget the “giant bonfires of the convents, or the profanations of churches” (18), attacking their feelings with it. That is why they are concerned about this equality of the sexes in the political sphere, because they believe that, although it is a logical and current measure, it can be transformed into an unjust and counterproductive movement to the development of the Republic.

One of the greatest defenders of women’s suffrage would be Clara Campoamor, a member of the Radical Party in Madrid, expressing strongly that Spanish women had sufficient capacity and the necessary maturity to cast their votes in elections (Arbeloa, 2006, p. 56). Contrary to these statements, we find Victoria Kent (Balaguer, 2009, pp. 27-28), of the Radical-Socialist party, who opposed women’s suffrage with the same arguments about the lack of schooling, culture and clericalism in Spanish women, the time had not come yet, from her point of view, to grant the vote to a will like the Spanish female that, due to these shortcomings, causes her to either “pronounce herself blindly or obey false advice” (19). Campoamor would receive criticism for the so-called “experiment in the female vote” that was to be held in 1933 with the first elections in which women would be able to participate. One of the main criticisms to Campoamor was that she gave women a value that, from the anti-clerical republican perspective, they do not have, because women in Spain have not yet acquired the state of culture necessary to think freely, to feel freely, to show what their wish is and what their idea is (20). On the contrary, Clara Campoamor that women have been redeemed, with these measures of the Republic, from the unjust exclusion and oblivion to which they had been prostrated. And this is precisely why, according to Campoamor, women will never jeopardize the democratic and liberal Republic, being a partner with it of the unstoppable social change of women (21).

Precisely because of this lack of confidence in the reasoning of women, a recurring theme in the leftist newspapers of Malaga before the elections of 1933, will be the lucubration regarding what women will vote. From the socialist ranks it is clear:

The Spanish woman of the privilege classes, who was assaulted in her feelings, and in her pocket with the agrarian reform, will vote for the extreme right. The woman of the middle class, also wounded in her religion and not benefited in her pocket, will vote for the radicals, and the woman of the people will vote where she is told and vote for those to whom she owes the gratitude of a loaf of bread. They all will agree in not voting to the socialists, because the socialists, yes, they have achieved with their policy to hurt those of above, to mock those in the middle and not to benefit those below. A demonstrative program of spiteful and aggressive ineptitude (22).

This association of women with the right wing was done in 1932, when Gil Robles and Lamamié de Clairac gave some lectures at the Cervantes Theater in Malaga. In view of this public act, the anticlerical media echoed by affirming that “the cream of our good reactionary society, our most illustrious cassocks, the most beautiful specimens of feminine prudishness and piousness, were the only recipient where the brew was poured” (23). It will be this traditional woman, this “monarchy-advocating lady” bored with religious prejudices who, faced with what she considers “bankruptcy of her traditions and her principles, will go out to look for a fight, impelled by the conjugal mandate or by the catechist council” (24).

It is for all of this that a campaign was launched from the Republican press to redirect the female vote to the left nominations. For this, the first thing they worked hard to make clear is that the Republic was not against religion since no one should be persecuted for their religious beliefs. Therefore, the “Republic is not Catholic, or Protestant, or Jewish, it is secular, because a peace regime must be outside the controversies of dogmatism and because the political and administrative functions in general, must be separated from them”(25). On the other hand, they do want to make it clear that it is the Republic the one that, with the Constitution of December 9, 1931 and the granting of a vote to women, has dignified them by equating them with men and granting them the same rights as men (26). And this is precisely why, even from the same Republican women’s sector, they insist that every woman, either rich or poor, solvent or not, by the mere fact of being Spanish is obligated for more than two years before a very large and unpaid debt (27). At this point, we should present the distinction that was made of women in two large groups or types: on the one hand, that young woman, who is liberating herself through work, education, feminism, which she sees in the Republic the only way out to progress and the evolution of women in their social aspirations and therefore they will vote for left parties. On the other hand, there is the woman

pseudo-intellectual, the pseudo-woman, the pseudo-ruler, those who are still dazzled by the love of big feet, the distinguished sportsman, those who accredit their sufficiency with the picaresque gesture of skipping lists, because they know that children are not brought from Paris, those who have amalgamated, in their cults, the soccer player Zamora, the bullfighter Ortega, the cinematographic Chevalier, the politician Gil Robles, without distinguishing any nuance in their feelings, those will vote for Primo de Rivera, who is young, who delivers speeches at meetings, to those who they adhere, speeches in which the poetic phrases of kisses and hugs are shuffled with the categories of pistols and “to finish at once”. Primo de Rivera, in addition, is a fascist, and that is fashionable (28).

This second type of woman, right-winged, fascist, Catholic, will be the one who puts more emphasis on her speech, trying to convince her of the benefits that the Republic brings to women and their rights, against what has been happening for years in which, because of the previous legislation, there were only duties for women, without any type of right. On the other hand, with the Republic, the woman “immediately obtained her rights of full citizenship, that of casting the vote, of acquiring or preserving her nationality without this intervening her change of status, the abrogation of all the privileges, so numerous, so overwhelming, so cruel, of the opposite sex” (29). It is to this liberation of women in search of an equality with men on which they are based to highlight the alleged debt that all women have contracted with the Republic, this being the time to pay off their debt by voting for the Republic: “If she is married, to ensure the future of her children within a regime of freedom, and if she is single, so that the conquests of democracy open new horizons to her wishes and her legitimate aspirations” (30).

However, an appeal is made for women not to abstain from using their vote in elections, because voting not only helps the one who they consider worthy of representing them, but they also fight against the one who, according to their opinion, will not do it well (31). Although each party will explain why women should vote for them, for example, the Radical Party, which exhort women to vote for it, arguing that women from Malaga owe “the Republic vindications never achieved in another regime, you must guarantee the economy of your home, the hygiene and education of your children, the work, the salary and the satisfaction of your husbands: Vote for the candidacy of the Radical Party”(32).

(10) AMM. Amanecer, December 16, 1932, p. 1.

(11) AMM. El Popular , December 5, 1931, p. 1.

(12) AMM. El Popular , December 5, 1931, p. 1.

(13) AMM . El Popular, November 10, 1931, p. 1.

(14) AMM . El Popular, November 16, 1933, p. 16.

(15) AMM. Amanecer, October 9, 1931, p. 1.

(16) AMM. Amanecer, January 12, 1993, p.12.

(17) AMM. El Popular, November 10, 1931, p. 1.

(18) AMM. El Popular, November 8, 1933, p. 3.

(19) AMM. Amanecer, 10 July 10, 1931, p. 1.

(20) AMM. Amanecer, October 09, 1931, p. 1.

(21) AMM. El Popular, November, 13, 1931, p. 1.

(22) AMM. El Popular, November 8, 1933, p. 3.

(23) AMM. El Popular, January 6, 1932, p. 8.

(24) AMM. Amanecer, April 16, 1932, p. 1

(25) AMM. El Popular, November 9, 1933, p. 16.

(26) AMM. El Popular, November 12, 1933, p. 1.

(27) AMM. El Popular, November 15, 1933, p. 1.

(28) AMM. El Popular, November 10, 1993, p.1.

(29) AMM. El Popular, November 15, 1933, p. 1.

(30) AMM. El Popular, November 12, 1933, p. 12.

(31) AMM. El Popular, November 8, 1933, p. 16.

(32) AMM. El Popular, November 2, 1933, p.1.

Source: AMM, El Popular, 09-11-1933.

Image 1. Press cutting.

At present we are witnessing an intense female-vote-capturing campaign by all parties, but especially by the Radical Republican Party and the Socialist Party. The explanation to this action is the belief that “there is a huge numerical superiority of the voting woman, which exceeds 30% of the male figure”, and that is why “the greatest compliments, the best, the biggest and most flowery of political propaganda are directed to her” (33). But, are these figures real in the Spanish population of the time?

(33) AMM. El Popular, November 16, 1933, p. 3.

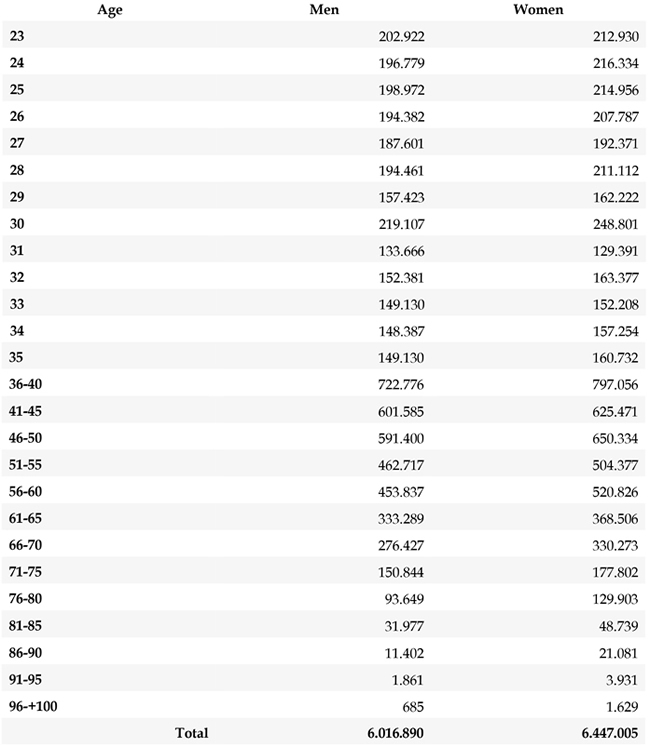

Table 1. Spanish population in 1930 (adults).

Source: own elaboration with data from the National Institute of Statistics.

As we can see in the population data we have for the year 1930, these do not show a high difference in the total number of people of legal age with the right to vote by sex, nor is there in any age range in the male population a significant decline that refers to the collateral damage of the First World War. What is more, in the census carried out in 1933 (34), the number of female voters amounted to 6,849,426, as compared to a male population of 6,337,885, so that there is not such argued difference of 30% higher female vote, the female census being only 7.4% more.

Anyway, the amount of nearly seven million people voting for the first time generated all kinds of doubts about the future of the Republic, an active anti-clerical campaign focusing on women to remove them from that supposed domain and influence of the clergy, as we have seen, so that they did not vote what others said but voted in freedom and conscience. And if this freedom and conscience is for the republican vote or the left in general, better (35). That is why, repeatedly, we see in the newspaper statements such as the following:

Do not let yourself be led, in this political moment, by the spontaneous apostles of the Christian Church; be assured that, if Christ returned to earth, they would be the first merchants to suffer the scourge of the avenging whip on their backs. Because his reign, as it prevails inside consciences, cannot be pennant of hook for greedy assaults of Power, and because to go burning the churches is as abusive as imposing, from the Government, the obligatory submission to a certain religion (36).

In this anti-clerical propaganda regarding women’s suffrage, they insist on how damaging it would be if they voted “induced or fanaticism-aroused by mistaken beliefs, thus betraying their own” (37). That is why they harangue women so that their vote should not “smell like wax or gunpowder. It must smell like freshly cut flower, clean feeling of passions, sectarian-free ideas. It must have the delight of kiss and wings of song” (38) .

(34) The data related to this electoral census of 1933 can be found detailed in the historical record of the National Institute of Statistics: http://www.ine.es/inebaseweb/pdfDispacher.do?td=102645

(35) AMM. El Popular, November 9, 1933, p. 16.

(36) AMM. El Popular, November 8, 1933, p. 16.

(37) AMM. El Popular, November 18, 1933, p. 6.

(38) AMM. El Popular, November 5, 1933, p. 3.

4.2. Women and the right to vote. After the elections of 1933

After the elections of 1933, these gave a favorable result to the right-wing parties. The simplistic reading on this question that is going to be done in the republican media will tend to blame women for this result, especially Catholic women. Lerroux himself will make this claim. In response to the question of to what he attributes this victory of the right wing in the elections, Lerroux openly declares that the first fundamental cause of this result has been the woman of religious convictions, because

a revolver has been placed in the hands of the woman, and then she has been offended in her most intimate feelings, in her religious conscience, and whenever a person carrying a weapon in her hand is offended, she shoots it. There was no need to have carried out that policy of religious persecution that has hurt the feelings rooted in the Spanish woman. She was first given the vote and later made subject to an aggression. What women have done now was natural (39).

In addition to this anti-clerical discourse, Lerroux links it with the classic argument, previously analyzed, of the female lack of culture in Spain, as opposed to women from other countries where they have a greater culture and may have a greater ability to discern what is right of what is not

It must also be borne in mind that women do not have in Spain the same degree of awareness and political preparation that characterizes women in other countries. There are nations that have suffered the rigors of war or the revolutions that followed, and also the creation of new States that the war itself produced, they have been able to form a culture and a political preparation that Spain lacks. In these countries, women, like men, know at every moment what they should do according to national conveniences. In Spain. No. Women do not yet balance their feeling with their understanding (40).

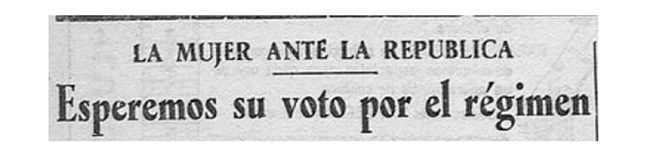

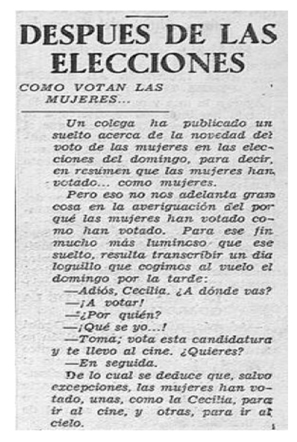

This feeling of defeat of the left wing in favor of the right motivated by women’s suffrage is going to be present in society, jokes about that issue being made, but an anti-clerical misogynistic feeling arises where women are placed in two possible scenarios: either they are silly easily-falling-in-love or they are Catholic. So we can testify in Image 2 taken from the newspaper El Popular.

(39) AMM. El Popular, November 23, 1933, p. 1

(40) Ibídem, p. 1.

Source: AMM, El Popular, November 25, 1933, p. 1.

Image 2. Press article.

It is curious that, weeks after the elections, the topic to be discussed about women is once again the channeling of their lives towards marriage and home. It will give a twist on the subject. And while it is true that the fact that women must prepare themselves, study to be able to earn their bread when the time is right, it is also true that the goal of female life is the constitution of a home and the creation of a family; because, according to these left-winged media, this represents the most important and superior social gear than any title. That is why women continue to be confined within home, secluded, quiet, submissive. Because the best career that the woman of insufficient intellect can choose: that of a housewife; more useful to the family and therefore to society than that bunch of female know-it-alls we suffer from, and who live convinced of the salvation of society, it is to monopolize the professions of men, forgetting that this is not the call by nature, namely Childcare and Home Economics (41).

With the arrival of 1936, we again witnessed an upturn in the interest of the republican press towards women. One of the aspects to be highlighted will be the recognition of the existence of feminism in society. Feminism that is quite combated not only in relation to the incorporation of women into work, study, politics, suffrage, etc., everything we have been seeing throughout these lines; but which is also going to be fought from a physical point of view. There are canons of beauty and behavior delimited for each sex, and women, unquestionably, cannot resemble males, because “the cigarette, the jacket, the masculine language - no, no, that is neither feminism nor is it proper to modern women! They will be what they want to call themselves, but the first thing that you have to be to be a woman is to be very feminine” (42).

This surge of interest in women is motivated by the third and, ultimately, last elections to be held in the Second Republic. Given this fact, we have the republican press in continuous criticism of Catholic women, with the same misogyny and ideology that we have been seeing throughout this period of time. The anticlerical, repetitive attack, again raising the voice arguing that there are still millions of women “who will go to the polls as sheep flocks go to slaughterhouse, gregarious instinct, believing in their holy simplicity that they defend the Religion, the Homeland, the Family, the Order, Justice, everything with a capital letter, when what they do is deny all that and be accomplices of its destruction” (43). It is significant to observe the increase in the contemptuous tone towards these women, the majority in Spain according to them, thus vindicating the role of the man as the one who must guide his foolish woman:

It is absolutely necessary that, in every home, men take care of illuminating the asleep brains, not imposing theories, but preventing their wives from being influenced, so they can think by themselves. It is necessary to get them to read, to be informed, to feel truly mothers and wives and companions of those who work in the unhealthy workshops and in the depths of mines. Let them know that it is not about destroying religion, or the homeland, or society, but about unmasking everything that usurps its name (44).

(41) AMM. El Popular, November 30, 1933, p. 3.

(42) AMM. El Popular, January 2, 1936, p. 8.

(43) AMM. El Popular, January 11, 1936, p. 12.

(44) Ibídem, p. 12.

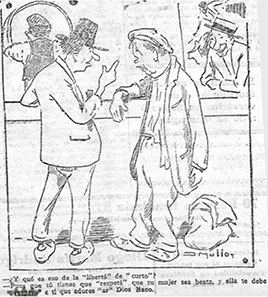

4.3. Graphic humor as a resource of anticlericalism

As Solomon (2003, p.48) points out, as with other aspects of anti-clerical ideology, the existing opinion about women was also transmitted through graphic representations in republican newspapers. Indeed, much of what has been analyzed above can be seen in the three images that, due to space limitations, we have selected from others and that we are going to analyze below to serve as a sample of this fact.

Source: AMM, El Popular, July 29, 1931.

Image 3. Graphic section.

In Image 3 we see two men at the counter of a barroom talking about the freedom of worship, and we can read the following “because you have to respect that your wife is pious, and she must respect that you worship God Bacchus” We return with the stereotype of the Catholic woman, pious, implying that what prevails in the society of Malaga is this type of woman. Instead, he makes it clear that men are not pious, they are not Catholic but, instead, they worship other gods.

Source: AMM, El Popular, January 24, 1932.

Image 4. Graphic Section.

In Image 4, the woman of lower class is represented, with a broom in her hand, a paradigm of illiteracy in Malaga that we have analyzed. In this vignette, the woman questions him if a sweep is needed, and the man replies ironically “Yes, but it starts on the right, which is more precise”. With the recent approval of women’s suffrage, it is necessary to make clear in all possible ways that it is necessary to instruct women so that they learn where their vote should go. Thus, taken as humor, lectures on the need to sweep the right, political, in future elections.

Source: AMM, El Popular, April 20, 1933.

Image 5. Graphic section.

Returning to the topic of the vote, in Image 5 we saw three people, a man with two women of old and demure appearance. The satire in this case goes back to delve into the elections of 1933, where the man tells the women they should be prepared for the elections and they answer “yes, we will consult with our confessor”. It delves into the anticlerical idea that women move according to the dictates of the priest, clearly denouncing the alleged clerical tactic of influencing the conscience of the man, including his vote, through his wife.

However, under the anticlerical perspective, the role played by women will be of extreme importance as it is at the service of clerical socio-ideological oppression (Salomón, 2005, p. 107).

5. CONCLUSIONS

By means of this piece of research, we have analyzed the vision that was held of women from anti-clerical republican stances. The first question that we have been able to solve has been the role assigned to women and to what extent republican men are willing to give in, because, although they accept women’s demands for equality, they still want to keep women within home in their role as mothers, wives and social beings, based on a supposed natural law that should govern the feminine gender. The recommendations found, even from other women, affect this path.

We have been able to show how there was a preconceived idea by this anticlerical republicanism, somewhat misogynistic, regarding women’s relationship with the clergy and the repercussion that this had on the family and social environment. a weak, uneducated, pious woman, with no capacity for discernment has been portrayed, who believes her confessor blindly, obeying him in everything, to the detriment of her husband and putting the Republic itself at risk. The grudge of this anticlericalism against the Church in general and, especially, against the Religious Orders, Jesuits to the head, caused, as a rule, distrust of all women by the mere fact of being so. That is why in this anti-clerical discourse the man is warned of how he should act before his wife and of the supposed danger he is with the Church, since she, under this anticlerical perspective, is an instrument of social oppression by accepting and spreading the clerical ideology.

Starting from this preconceived idea of women caused mistrust of their correct reasoning to settle down, if it was she or her confessor who would pass judgment and act. Hence the great controversy over the acceptance or not of female suffrage and the large number of articles published in this press calling women to vote for the Republic, touching sensitive issues such as that the Republic was not against religion or selling Republican goodness and the great favor it has done to women by allowing them access to the vote. Something for which women must feel in debt.

Finally, we have demonstrated the doubts, fears and misgivings of men when faced with this incipient Spanish feminism, both in regard to the demand for freedom or equality with them, and, especially, for women’s access to the world of work. A world in which they have been placed in the spotlight because, according to men, they take away man’s job and, in addition, charge a lower salary for it, which translates into an impossible competition to face. Hence, they emphasize the idea that women do work, but always in natural professions to their condition as women, that is, those of care, attention and teaching of third parties.

REFERENCES

1. Alía Miranda, F. (2008). Técnicas de investigación para historiadores. Madrid: Síntesis.

2. Arbeloa, V. M. (2006). La semana trágica de la Iglesia en España (8-14 octubre 1931). Madrid: Encuentro.

3. Balaguer, M. L. (2009). Victoria Kent: vida y obra. Corts: Anuario de derecho parlamentario, 21, 17-34.

4. Beasgoechea Gangoiti, J. Mª. y Otero Carvahal, L. E. (Eds.) (2015). Las nuevas clases medias urbanas. Transformación y cambio social en España, 1900-1936. Madrid: Catarata.

5. Cueva Merino, J. de la (1997). Movilización política e identidad anticlerical, 1898 – 1910. Ayer, 27, 101-125.

6. Cueva Merino, J. de la (1998). El anticlericalismo en la Segunda República y la Guerra Civil, en La Parra, E. & Suárez, M. (Eds.). El anticlericalismo en la España Contemporánea (pp. 211-301). Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.

7. Díez Fuentes, J. M. (1995). República y primer franquismo: la mujer española entre el esplendor y la miseria, 1930-1950. Alternativas. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 3, 23-40.

8. García Galindo, J. A. (1999). La prensa malagueña 1900-1931. Estudio descriptivo y analítico. Málaga: Ayuntamiento de Málaga.

9. Mateo Avilés, E. de (1987). Piedades e impiedades de los malagueños en el siglo XIX. Málaga: Montes.

10. Monterde García, J. C. (2010). Algunos aspectos sobre el voto femenino en la II República Española: debates parlamentarios. Anuario de la Facultad de Derecho, 28, 261-277.

11. Ramos, M. D. (1988). Luces y sombras en torno a una polémica: la concesión del voto femenino (1931-1933). Baética, 11, 564 – 573.

12. Ramos, M. D. (1993). Mujeres e historia. Reflexiones sobre experiencias vividas en los espacios públicos y privados. Málaga: Universidad de Málaga.

13. Requena, F. (2002). Vida religiosa y espiritual en la España de principios del siglo XX. Anuario de historia de la Iglesia, 11, 39-68.

14. Revuelta, M. (1991). La Compañía de Jesús en la España Contemporánea. Tomo II. Madrid: Universidad Pontificia Comillas.

15. Rivas Arjona, M. (2013). II República española y prostitución: el camino hacia la aprobación del Decreto abolicionista de 1935. Arenal, 20(2), 345-368.

16. Salomón Chéliz, M. P. (1999). Republicanismo y rivalidad con el clero: movilización de la protesta anticlerical en Aragón 1900-1913. Studia histórica. Historia Contemporánea, 17, 211-229.

17. Salomón Chéliz, M. P. (2003). Beatas sojuzgadas por el clero: La imagen de las mujeres en el discurso anticlerical en la España del primer tercio del siglo XX. Feminismo/s, 2, 41-58.

18. Salomón Chéliz, M. P. (2005). Las mujeres en la cultura política republicana: Religión y anticlericalismo. Historia Social, 53, 103-118.

19. Salomón Chéliz, M. P. (2011). Devotas, mojigatas, fanáticas y libidinosas. Anticlericalismo y antifeminismo en el discurso republicano a fines del siglo XIX, en Aguado, A. & Ortega, T. (Eds.), Feminismos y antifeminismos. Culturas políticas identidades de género en la España del siglo XX (pp. 71-98). Valencia: PUV.

20. Suárez Cortina, M. (2000). El gorro frigio. Liberalismo, Democracia y Republicanismo en la Restauración. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.

21. Suárez Cortina, M. (2014). Entre cirios y garrotes. Política y religión en la España Contemporánea, 1808-1936. Santander: Universidad de Cantabria.

22. Vilanova Ribas, M., y Moreno Julia, F. X. (1991). Atlas de la evolución del analfabetismo en España de 1887 a 1981, en Resúmenes de premios nacionales de investigación e innovación educativas 1990 (pp. 7-30). Madrid: Centro de Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

AUTHORS

Israel David Medina Ruiz: He has a degree in History from the University of Málaga, a degree in Primary Education from the Camilo José Cela University (Madrid), a Master’s Degree in Compulsory Secondary Education (UMA) and a doctorate from the Department of Modern and Contemporary History in the doctorate program Advanced Studies in Humanities, at the University of Málaga. He has made his international research stay at the Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (CNR), at the headquarters in Rome, allowing him to research archives of worldwide relevance such as the Archivio Segreto Vaticano. His other line of research deals with teaching innovation and new technologies in education, which has led him to participate as a speaker at several conferences and international conferences.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6880-780X

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=WoCbVPcAAAAJ&hl=es

Antonio Rafael Fernández Paradas: He has a PhD in History of Art from the University of Malaga, with a doctoral thesis entitled Historiography and Methodologies of the History of Furniture in Spain (1872-2011). A state of affairs. Graduated in History of Art and Bachelor of Documentation from the University of Granada. Master in Appraisal and Appraisal of Antiques and Works of Art by the University of Alcalá de Henares. Specialist in sculpture, furniture and decorative arts, his lines of research deal with religious iconography, art history, gender and homosexuality, baroque sculpture, the Social Science Didactics, etc. He is a member of several research groups, such as the Research Group of the Junta de Andalucía HUM-985, entitled “UNES. University, school and society. Social Sciences”, research member since 10/02/2017 until today. He is currently the principal investigator of the multidisciplinary study of the influence of creativity and corporate happiness in the sustainable development -economic, social and environmentally-of the territories. Financial institution: Polytechnic University of Salesiana of Ecuador. Duration: 04/01/2017 to 04/01/2018. He is currently Assistant Professor Doctor of the University of Granada, where he teaches in the Department of Social Science Didactics of the Faculty of Education Sciences, and teacher of the Master’s Art and Advertising of the University of Vigo.

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=XoViNywAAAAJ&hl=es