Figure 1. Model of variables involved in LeBlanc's musical preferences.

doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.154.e1236

RESEARCH

STUDENTS’ MUSICAL PREFERENCES: TOWARDS RECOGNITION OF THEIR CULTURAL IDENTITIES

LAS PREFERENCIAS MUSICALES DE LOS ESTUDIANTES: HACIA UN RECONOCIMIENTO DE SUS IDENTIDADES CULTURALES

PREFERÊNCIAS MUSICAIS DOS ALUNOS: PARA O RECONHECIMENTO DE SUAS IDENTIDADES

Pablo Marín-Liébana

José Salvador Blasco Magraner1

Ana María Botella Nicolás1

1University of Valencia. Spain.

ABSTRACT

Various traditions of critical music education sustain the need to recognize students’ identities by incorporating their musical preferences, which belong mainly to popular music, in the curriculum. However, it is not yet widely used in educational systems and teachers, who consider it aesthetically inferior, commonly reject it. Nevertheless, in-depth knowledge of the construction and psychosocial implications of these preferences could contribute to increasing their inclusion in the educational field. In this sense, this article reviews 105 works on the main theories, models, and evolutionary studies that explain them, the relationship between preferences and musical identities, the concept of popular music as an object of study of musicology, and the initiatives that have already incorporated it into the classroom. As will be seen, students' musical preferences are not mere fads but complex constructs that help them build their identity and establish positive social relationships. Some initiatives such as Modern Band or Little Kids Rock have already incorporated it in the music classroom, while the legislation of the Nordic countries is the most advanced one in this regard, having established that the interests and preferences of students must be recognized and included as part of the curriculum.

KEY WORDS: Music education, Critical education, Identity, Recognition, Musical preferences, Student experience, Popular music.

RESUMEN

Diversas tradiciones de educación musical crítica sostienen la necesidad de reconocer las identidades de los estudiantes mediante la incorporación curricular de sus preferencias musicales, las cuales pertenecen principalmente a la música popular urbana. Sin embargo, esta todavía no es utilizada de manera generalizada en los diferentes sistemas educativos y es comúnmente rechazada por los docentes, quienes la consideran estéticamente inferior. No obstante, un conocimiento en profundidad de la construcción e implicaciones psicosociales de dichas preferencias podría contribuir a aumentar su inclusión en el ámbito educativo. En este sentido, este artículo realiza una revisión bibliográfica de 105 trabajos sobre las principales teorías, modelos y estudios evolutivos que las explican, la relación entre preferencias e identidades musicales, el concepto de música popular urbana como objeto de estudio de la musicología y las iniciativas que ya la han incorporado dentro del aula. Como se verá, las preferencias musicales de los estudiantes no son meras modas pasajeras sino complejos constructos que les ayudan a construir su identidad personal y a establecer relaciones sociales positivas. Algunas iniciativas como Modern Band o Little Kids Rock ya la han incorporada en el aula de música, mientras que la legislación de los países nórdicos es la más avanzada en este aspecto, habiendo establecido que los intereses y preferencias de los estudiantes deben ser reconocidos e incluidos como parte del currículum.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Educación musical, Educación crítica, Identidad, Reconocimiento, Preferencias musicales, Experiencia de los estudiantes, Música popular urbana.

RESUMO

Diversas tradições da educação musical crítica falam sobre a necessidade de reconhecer as identidades dos alunos através da incorporação nos currículos de estudo as suas preferências musicais, às quais pertencem principalmente a música popular urbana. Porém, ainda não é utilizada de forma geral nos diferentes sistemas educativos e é comumente rejeitada pelos professores, que a consideram esteticamente inferior. Não obstante, um conhecimento aprofundado da construção e implicações psicossociais de tais preferências poderia contribuir a aumentar sua inclusão no âmbito educativo. Neste sentido, este artigo faz uma revisão bibliográfica de 105 trabalhos sobre as principais teorias, modelos e estudos evolutivos que as explicam, a relação entre as preferências e identidades musicais, o conceito de música popular urbana como objeto de estudo da musicologia e as iniciativas que já têm sido feitas dentro da aula. Como poderá ser observado as preferências musicais dos estudantes não são somente modismos passageiros mas complexos construtos que lhes ajudam a construir sua identidade pessoal e a estabelecer relações sociais positivas. Algumas iniciativas como Modern Band o Little Kids Rock já tem feito o próprio nas aulas de música, enquanto a legislação dos países nórdicos é a mais avançada nesse aspecto, tendo estabelecido que os interesses e preferências dos estudantes devem ser reconhecidos e incluídos como parte do currículo.

PALAVRAS CHAVE: Educação musical, educação crítica, identidade, reconhecimento, preferências musicais, experiência dos estudantes, música popular urbana.

Correspondence:

Pablo Marín-Liébana. University of Valencia. Spain. Pablo.Marin-Liebana@uv.es

José Salvador Blasco Magraner. University of Valencia. Spain. j.salvador.blasco@uv.es

Ana María Botella Nicolás. University of Valencia. Spain. Ana.Maria.Botella@uv.es

Received: 14/05/2020.

Accepted: 23/06/2020.

Published: 12/03/2021.

How to cite this article:

Marín-Liébana, P., Blasco Magraner, J. S. y Botella Nicolás, A. M. (2021). Las preferencias musicales de los estudiantes: hacia un reconocimiento de sus identidades culturales. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 154, 43-67. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.154.e1236

http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1236

Financiación: Work funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sport of the Government of Spain.

Translation by Paula González (Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Venezuela).

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, interest in the study and recognition of musical identities in the educational field has grown (Westerlund, Partti, & Karlslen, 2017). Various traditions within critical music education (Abril, 2013; Gowan, 2016; Roberts and Campbell, 2015) propose to give a voice to students so that they participate in the selection of the contents that are addressed in the classroom. This implies understanding their enculturation processes and musical preferences to incorporate them at different curricular levels (Green, 2004; Laurence, 2009; Williams, 2017). However, these preferences belong mainly to urban popular music (UPM), which generates rejection by teachers for being considered aesthetically inferior to academic and folkloric-traditional music, or even morally and physically harmful for the students themselves (Boespflug, 2004; Hebert and Campbell, 2000; Kratus, 2019; Reimer, 2004).

However, as will be seen later, students' musical preferences build their cultural identity and allow them to establish positive social relationships (Abrams, 2009). In this sense, the knowledge of these understood as an operational construct that represents the specific taste shown by the subjects (Leblanc, 1984), can be useful for those teachers who want to initiate a process of recognition of the identity diversity of the groups they work with. In this sense, the study of musical preferences has been approached in explanatory and predictive terms, both on the factors that condition their development, and on the lifestyles and identity traits that are associated with them. Here the main theories and models, the studies that have addressed musical preferences from an evolutionary point of view, their relationship with identities, and some theoretical and practical initiatives that have incorporated the UPM in the educational field as a way of approaching them are presented.

2. OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY

The objective of this article is to deepen the knowledge about the musical preferences of primary and secondary school students, so it contributes to overcoming the rejection and prejudices existing in the educational field about the music that they typically consume. For this, a bibliographic review has been carried out on the concepts of musical preferences, musical identities, and urban popular music. Initially, a search was carried out in the Web of Science and Scopus databases. Among the results obtained, those works that explain the theories and models on the construction of musical preferences and their relationship with identities were selected, as well as those that define the concept of urban popular music as an object of study of musicology and those that deal with its incorporation into the educational field.

From the articles found, the snowball sample extension technique was used to identify foundational and relevant works. In this sense, manuals such as Musical Identities (MacDonald, Hargreaves, and Miell, 2002), Handbook of Musical Identities (MacDonald, Hargreaves, and Miell, 2017), and The Child as Musician: A Handbook of Musical Development (McPherson, 2006) were incorporated regarding musical preferences and identities; and The Routledge Research Companion to Popular Music Education (Smith, Moir, Brennan, Rambarran, and Kirkman, 2017b), The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music (Bennett and Waksman, 2015b), and The Oxford Handbook of Popular Music in the Nordic Countries ( Holt and Kärjä, 2017), regarding urban popular music. In the same way, the references found in these manuals contributed to expanding the study sample. Finally, this amounted to a total of 105 papers reviewed.

3. RESULTS

Next, the results obtained are presented organized in four axes. First, the theories and models that explain the formation of musical preferences. Second, the studies that address its evaluation in children and teenagers. Third, the relationships between musical preferences and identities. Finally, a section in which the UPM is conceptualized, and some examples of incorporation in the educational field are presented.

3.1. Theories and models

One of the lines of research on musical preferences with the greatest scientific production is that constituted by experimental studies on aesthetics (Hargreaves, North, and Tarrant, 2006), within which two main theories have coexisted since the 1980s. On the one hand, one is based on the level of excitement that a certain stimulus produces on the autonomic nervous system. This is based on a model of variables developed by Berlyne (1971) and maintains that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between musical preferences and the degree of familiarity and complexity of the pieces (Hargreaves, 1986; Hargreaves et al., 2006). In this way, a high degree of preference is related to an average level of both variables, while if they present low or high levels, the degree of the former decreases. Numerous studies based on this theory attest to its current validity (Chmiel and Schubert, 2017).

The other theory has a cognitive basis and maintains that the level of preference increases as the stimulus prototypically approaches the category to which it belongs (Martindale and Moore, 1988). That is, the auditory judgment is conditioned by the potential fit of a piece within a set of characteristics previously accepted as preferred. Despite the rivalry that both have maintained in the scientific literature and the criticisms received (North and Hargreaves, 2000; Hekkert and Snelders, 1995), it is possible to establish bridges between them and acknowledge the validity of both. For example, a high degree of novelty in a piece may be related to a certain distance from the prototype (Hargreaves et al., 2006), so that the two approaches could work together when determining musical preferences.

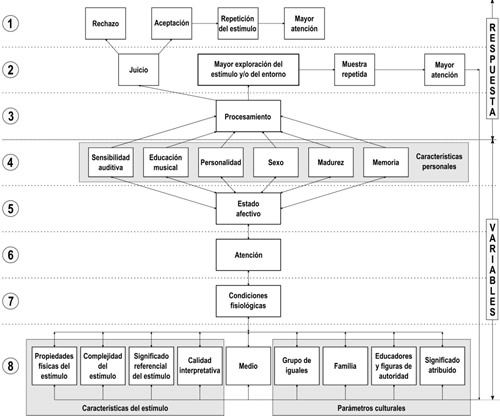

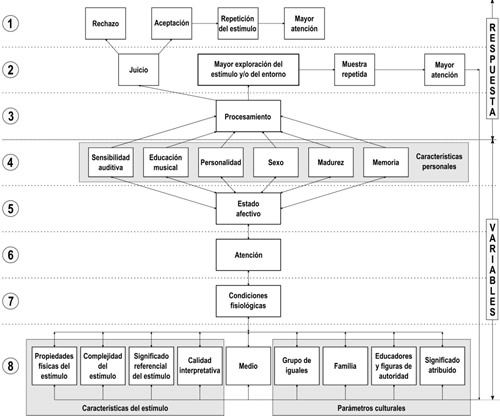

For his part, LeBlanc (1980) proposes a sequencing model of musical preferences based on a series of variables and a response pattern (figure 1). The model, divided into an eight-level hierarchy, proposes a hierarchical flow that aims to explain what characteristics of the sound stimulus, cultural parameters, personal characteristics, and psychological factors influence the rejection or acceptance of a certain piece of music.

Another proposed model is that of reciprocal feedback in the musical response (Hargreaves, North, & Tarrant, 2010), which presents a triangle in which the characteristics of the music itself, of the person who listens to it, and of the context in which listening occurs, are the ones that condition the response to the sound stimulus. In this way, to the variables of complexity, familiarity, and prototypicality, those of age, gender, personality, and musical experiences of the subject are added, as well as others related to the listening situation such as the type of company, the specific place, or the sociocultural inferences.

Source: Leblanc, 1980.

Figure 1. Model of variables involved in LeBlanc's musical preferences.

Source: Hargreaves, North, and Tarrant, 2010.

Figure 2. Model of reciprocal feedback in the musical response.

3.2. Evolutionary studies.

Regarding the studies carried out under an evolutionary approach, those related to the idea of auditory openness stand out, coined by Hargreaves (1982) as a hypothesis according to which younger children would be less enculturated and, therefore, more open to any type of music beyond the conventions. Later, LeBlanc (cited in Leblanc, Sims, Siivola, & Obert, 1996) equated this concept with that of auditory tolerance, associated both with the development of musical preferences, and made four hypotheses: (1) Younger children have a greater auditory aperture, (2) auditory aperture decreases when they enter adolescence, (3) there is a partial increase in early adulthood, and (4) it decreases as people get older. Since then, auditory openness has become a specific line of research.

For example, one study revealed that the level of general preference for a piece of music decreases between the ages of 11 and 13 (Leblanc et al., 1996), especially regarding classical music (Hargreaves, Comber, & Colley, 1995). Other authors have placed this reduction in auditory openness in earlier ages, around 7 and 8 years old (Reinhard Kopiez, and Lehmann, 2008; Schurig, Busch, and Strauß, 2012). However, these studies have recently been put into question by Louven (2016), who argues that tolerance towards a type of music is not the same as liking it, in the same way, that it should not be analyzed at the same level the refusal to experiment with new music and not expressing a preference for a piece while listening to it.

On the other hand, various researches on the evolution of musical taste identify a turning point in the 9 to 11 age range regarding musical styles. On the one hand, Hargreaves, North, and Tarrant (2010) point out that around 10 and 11 years of age, preferences for pop music are manifested to the detriment of other styles, which evolutionarily coincides with the moment in which the sensitivity to the violation of group norms and to being labeled as the black sheep develops (Marques, 1988). In a similar line, Grembis and Schellberg (2003) conducted a study with 591 primary school students and found that from the age of 9 there begins to be a rejection of classical, contemporary, and folk music, with which they are not familiar, and a preference for pop is awakened. Furthermore, this situation seems to remain constant over time, as shown by two previous studies carried out in the 1950s and 1970s.

In the first of them, Rogers (1957) studied the evolution of musical taste with a sample of 635 students between 9 and 18 years old and found that from the fourth grade (9-10 years old) the preferences for classical and folk music decrease in favor of urban popular music, and that this generally happens regardless of the rural or urban context of the center, the gender of the students, or the socioeconomic level of their families. In the second of them, Greer, Dorow, and Randall (1974) concluded on a sample of 134 students from the infant and primary education stages, that musical preferences vary as the courses progress, gaining interest in rock music and losing it for the rest.

These results are consistent with those found by various studies on the musical preferences of children and young people, which indicate that the UPM repertoire is the favorite one. Thus, a study carried out on a sample of 1,479 students between 8 and 14 years old found that 90% of those surveyed stated that they listened to pop, dance, rock, and R&B music of their choosing (Lamont, Hargreaves, Marshall, and Tarrant, 2003). In the same way, similar results were obtained in two studies carried out with secondary school students (Ligero, 2009; Santos, 2003) and another whose sample was individuals between 15 and 24 years old (Megías and Rodríguez, 2003).

3.3. Musical preferences and identities.

Studies on the relationship between musical preferences and the identities of individuals can be divided between those who conceive personality traits as a mediator between the two and those who argue that there is a direct relationship. Concerning the first group, there is a clear relationship between musical preferences and the personality of individuals (Delsing, Ter Bogt, Engels, & Meeus, 2008; Nave et al., 2018). In this sense, people consider that musical preferences reveal a lot of information about their personality and self-concepts (Dys, Schellenberg, and McLean, 2017; Rentfrow and Gosling, 2003). Similarly, they believe that they can be used to make judgments about the personal traits of others (Ziv, Sagi, & Basserman, 2008). These judgments, as social interactions, will in turn be mediated by the observer's musical preferences (Rentfrow and Gosling, 2006).

This relationship occurs because each music has a specific level of excitement that can be linked to certain individual characteristics and preferences for specific activities (Rentfrow and Gosling, 2006). Thus, Dunn, De Ruyter, and Bouwhuis (2011) found a relationship between neuroticism and a preference for classical music, as well as between a personality open to new experiences and a preference for jazz music. On the other hand, Vella and Mills (2017) not only found a positive relationship between said attitude of openness towards new experiences and a preference for reflective and complex styles such as jazz, but also blues and other more intense ones linked to rebellion, like rock and metal. However, this trait found an inverse relationship with cheerful and conventional music such as country or pop. On the other hand, they found that extroverts tended to prefer rhythmic and energetic music such as rap or soul, besides cheerful and conventional music (Vella & Mills, 2017). For their part, Greenberg et al (2016) found relationships between music with a low energy level and a friendly personality, between sad music and neuroticism, as well as between happy and deep music and an open personality.

Very close to this evidence is the research on the relationship between musical preferences and lifestyles. In this sense, UPM can be associated with progressive and sometimes antisocial political options, while classical music is linked to conservative options (North and Hargreaves, 2007a). In the same way, the preference for certain musical styles also finds echoes in the decisions that individuals make when choosing a newspaper, a radio station, a television channel or show, or a magazine (North and Hargreaves, 2007b), as well as in socio-economic issues such as wealth, educational level, employment, or health (North and Hargreaves, 2007c).

Regarding the groups that directly address the identity issue, Cook (2011) argues that Western or Westernized civilization is divided into a large number of subcultures, each with its own music, so deciding what music you listen to is a way to define your identity in front of others. In this sense, in the same way as with personality, musical preferences are part of the identity of individuals (Gardikiotis and Baltzis, 2010; Hargreaves, Miell, and MacDonald, 2002) and are used to project or infer it on others (Rentfrow and Gosling, 2006). In fact, the main reason we like our musical preferences is that they allow us to express our identity and values (Schäfer & Sedlmeier, 2009). Thus, various studies show that people tend to prefer music that is linked to their culture (Morrison and Lew, 2001; Teo, Hargreaves, and Lee, 2008), especially regarding the language of the lyrics (Abril and Flowers, 2007; Brittin, 2014). However, Dys, Schellenberg, and McLean (2017) point out that there is a degree of nuance between musical preferences and identities. In this way, while the first has to do with how much we like a certain genre, the second implies a certain commitment to it.

On the other hand, musical preferences affect our social relationships (Lonsdale and North, 2011). On the one hand, it has been seen that our tastes can be modified by the social feedback we receive (Schäfer et al., 2016). On the other hand, it has been seen that adapting to the musical preferences of others is a way of building, sustaining, and managing social relationships (Denes, Gasiorek, & Giles, 2016). Especially sensitive to the relationships between social identity and musical preferences is the stage of adolescence, where individuals use them to define their group identity and differentiate themselves from that of others (Tarrant, North, & Hargreaves, 2001).

Here, musical preferences act as a social distinctive and adolescents try to adjust their self-concept to the social identities of the groups associated with them (Hargreaves, MacDonald, & Miell, 2017; North & Hargreaves, 1999), while showing a preference for those styles whose stereotypical fans are similar to them (Lonsdale and North, 2017). Therefore, the choice of musical styles by adolescents is not so much a matter of trends, but a way of ascribing to a certain group and differentiating themselves from others, so their preferences can play an important role in the positive development of their identities and, in turn, in the development of positive social relationships (Abrams, 2009).

3.4. Incorporation of students' musical identities/preferences in educational programs: urban popular music.

Numerous studies confirm that the musical preferences of students in the second half of primary school and throughout secondary school belong to what is known as UPM (Cremades, Lorenzo, and Herrera, 2010; De Quadros and Quiles, 2010; de Vries, 2010; Dobrota and Ercegovac, 2019; Ho, 2017). However, despite having a disciplinary tradition within the field of musicology of over half a century (Bennett and Waksman, 2015a), the very concept of UPM has not yet been consensually defined. In this sense, its unstable and changing character makes it difficult to establish a satisfactory formulation that covers all uses, with the popular category being the most inaccessible (Connell and Gibson, 2003; Editors, 2005; Hesmodhalgh and Negus, 2002; Johnson, 2007, 2018; Middleton, 1990; Shuker, 2016; Stone, 2016). Instead of a definition, Frith (2004, pp. 3-4) offers a broad characterization of UPM:

Music made commercially, in a particular kind of legal (copyright) and economic (market) system. Music made using ever-changing technology, with particular reference to forms of recording or sound storage. Music, which is significantly experienced as mediated, tied up with the twentieth-century mass media of cinema, radio and television. Music which is primarily made for pleasure, with particular importance for the social and bodily pleasures of dance and public entertainment. Music which is formally hybrid, bringing together musical elements which cross social, cultural and geographical boundaries.

However, the author himself admits that this characterization is paradoxical because it can encompass any type of music and at the same time distinguishes UPM from other traditions or sound forms. Another characterization is the one carried out by Shuker (2016) when he identifies a series of elements associated with UPM, among which are its popularity, its commercial dimension, fashion, the recording industry, its ubiquity, the fact of being oriented towards young people, its Anglo-American origin in the early 1950s, and its current global character. Furthermore, at a formal level, he defines it as a hybrid of musical traditions, styles and genres, and influences, with the only common element being that it has a strong rhythmic component and, generally, although not exclusively, being electronically amplified.

These expressions of UPM, although not completely satisfactory, make it possible to differentiate it from Western academic music of European tradition and traditional and folk music (Frith, 2004). Given the possible overlap with the latter, Regev (2013) and Stone (2016) coincide in explaining that, while UPM is linked to urban overcrowding in industrial, modern, and commercial contexts, traditional and folk music, which also has a popular character, comes from rural and pre-modern contexts.

Regarding the use of UPM in educational contexts, various authors recognize in the Tanglewood Symposium, held in Massachusetts in 1967, one of its founding moments (Gurgel, 2019; Krikun, 2017; West and Clauhs, 2015). At this meeting, an agreement was reached that all the diversity of musical manifestations should be included in the educational curriculum (Choate, 1968, p. 139):

Music of all periods, styles, forms, and cultures belongs in the curriculum. The musical repertory should be expanded to involve music of our time in its rich variety, including currently popular teenage music and avant-garde music, American folk music, and the music of other cultures.

However, even though it was concluded that UPM should be incorporated into music education classrooms, this has not yet been done in a generalized way (West and Clauhs, 2015). For example, in the German context, Kertz-Welzel (2013) argues that there is a rejection of the subject of music education as a consequence of the gap between educational objectives and students' musical cultures, due to the prominence of the traditional notation, academic music of European tradition, music theory, and group singing of the school repertoire. In the Spanish case, Marín and Botella (2018) found that in the 5th and 6th-grade classrooms of primary education, classical-romantic, children's-school, and folkloric-traditional music repertoires predominate fundamentally, while only 5% of teachers incorporate the preferences of their students into their classrooms. Similarly, Ibarretxe and Vergara (2005) found that traditional and academic music were the most represented in primary school textbooks. These findings are in agreement with Westerlund, Parti, and Karlslen (2017), who argue that curricular policies prioritize a musical approach based on nationalism and the cultural superiority of the Western classical repertoire.

Even so, during the last decades, there has been an increase in the presence of UPM in schools, institutes, universities, and conservatories, as well as academic works about it, so we can speak of Popular Music Education (PME) as a field of knowledge (Gareth Dylan Smith, Moir, Brennan, Rambarran, & Kirkman, 2017a).

One of the first works that saw the light was Popular Music: a teacher's guide (Vulliamy and Lee, 1982), a kind of guide for the teacher with resources to address different styles. However, the main development of PME has taken place during the 21st century. Thus, one of its historical milestones was the Northwestern University Music Education Leadership Seminar (NUMELS), held in Illinois in 2002 under the title Popular Music and Music Education: Forging a Credible Policy, whose discussions were published two years later in the monograph Bridging the Gap. Popular Music and Music Education, assuming a new impulse within the field (Rodríguez, 2004). Also noteworthy are the birth in 2010 of the Association for Popular Music Education and its annual international congress (Gareth Dylan Smith et al., 2017a), the appearance in 2017 of the Journal of Popular Music Education, and the publication in the same year of the monographic volume The Routledge Research Companion to Popular Music Education (Gareth Dylan Smith, Moir, Brennan, Rambarran, and Kirkman, 2017b). However, Till (2017) points out that, despite the rapid development that the introduction of UPM in education is experiencing, there are few relevant publications on case studies or theoretical developments.

From a more practical perspective, the Musical Futures project was created in the United Kingdom in 2003, within the framework of The Paul Hamlyn Foundation, to create new methods of music education for young people between 11 and 19 years old (Gage, Low, and Reyes, 2019; Hallam, Creech, and McQueen, 2017a; Price, 2005). It currently operates as a non-profit organization that offers pedagogical foundation, lifelong learning, and resources for teachers and schools, not only in the United Kingdom, but also in North America, Australia, and Southeast Asia (Powell, Smith, and D'Amore, 2017). Having Lucy Green as the main ideologist, its objective is to introduce non-formal teaching and informal learning processes in more formal contexts, to implement activities that are participatory and meaningful for students (Bramley, 2017). This includes letting them choose what music they want to work with, who they want to do it with, and with what material resources (Powell et al., 2017).

In the United States, several organizations have emerged with similar objectives. Among them, Little Kids Rock stands out, which organizes workshops and provides educational and instrumental resources to public educational centers, and, as will be explained later, has developed Modern Band and Music as a Second Language as its own methods and approaches (Kindall-Smith, McKoy, and Mills, 2011). The great impact of this association on American society is supported by the participation of around 400,000 students between 2002 and 2017 (Krikun, 2017). Another methodology that is situated in a similar line is Soundcheck, in the Dutch context (Evelein, 2006). However, at the level of primary and secondary education, the Nordic countries are recognized as having a more developed trajectory (Christophersen and Gullberg, 2017; Till, 2017), as evidenced by a large number of publications in this regard (Georgii-Hemming and Westvall, 2010; Kallio, 2017; Karlsen, 2010; Partti and Westerlund, 2012; Prior, 2015).

For example, Norwegian law prescribes that students' musical background and the musical skills they acquire outside of school must be incorporated into the curriculum (Utdanningsdirektorate, 2006). In the Finnish case, the legislation encourages an analysis of the society and musical culture of its youth (Kallio and Väkëva, 2017) and it is common for schools to have microphones, drums, basses, and electric guitars, and that teachers' initial training requires competence in its use, as well as knowledge of studio recording techniques and live performance (Westerlund, 2006). This reality is consistent with the incorporation of these practices in teacher training programs in Scandinavian countries (Humpfreys, 2004).

But it is in Sweden where these practices are more established since, since the 1960s, educational legislation recognized the need to incorporate the needs and interests of students into the official curriculum, becoming, from the following decade, the repertoire of UPM and their informal learning systems commonplace in school classrooms (Hallam, Creech, & McQueen, 2017b). In this way, students often choose what they want to play and who they want to play with, forming small pop and rock bands based on hearing, trying, and playing; teachers focus on developing practical skills based on their interests and needs; and educational policy is broad enough so that both parties can build the curriculum in a negotiated way (Georgii-Hemming and Westvall, 2010).

However, a study in the process of publication has concluded that the situation of UPM in Spanish educational legislation is different. In this sense, Royal Decree 126/2014, of February 28th, which establishes the basic curriculum for Primary Education (Spain, 2014), does not make explicit reference to the musical identities of students. Although the mentions it makes about the repertoire indeed focus it from the point of view of the diversity and plurality of places, times, and styles in the performance block, which would potentially integrate the current UPM, the listening and movement blocks emphasize the concepts of cultural heritage and traditional music, respectively. Nor does the concretion of this text in Decree 108/2014, of July 4th, of the Consell, which establishes the curriculum and develops the general organization of Primary Education in the Valencian Community (Comunitat-Valenciana, 2014), mentions explicitly incorporating students' musical preferences into educational content. In this, the closest references are the knowledge of UPM instruments and the use of flamenco and jazz.

4. CONCLUSIONS

As has been seen, the musical preferences of students cannot be reduced to a mere passing trend lacking aesthetic value, but rather constitute a complex construct in which various elements participate. Among them are the characteristics of the sound stimulus, its physical properties, its degree of familiarity and complexity, its approach to a prototype, its performance quality; the characteristics of the subject, their age, gender, previous experiences, personality, cognitive abilities, their emotional responses; and the characteristics of the environment, the peer group, the family, the listening context, the attribution of authority.

At an evolutionary level, it has been found that around 10 years of age the auditory openness of students decreases, and a phase of rejection towards academic and folk music styles, in which they manifest preferences for UPM, begins. This coincides with the moment of entering adolescence, in which the peer group begins to have an important role in defining the individual's social identity and music is used as a symbol and ascription to a specific group. In this sense, it has been seen that musical preferences are related to personality, self-concept, lifestyles, and values.

However, despite the importance that students' musical preferences represent for the construction of their identities and the development of positive social relationships, they have not yet been incorporated into the educational curriculum in a generalized way. However, there are some initiatives to use UPM that can serve as a model for other countries or teachers who want to incorporate it into their classrooms. Among them are the Musical Futures project in the United Kingdom or Little Kids Rock in the United States. However, it is in the Nordic countries where there is a more developed tradition. Thus, in contexts such as Norway, Finland, or Sweden, the educational legislation establishes that the interests and preferences of students must be taken into account at the curricular level, which is complemented by teacher training and material resources following the demands that this change requires.

In this direction, it is suggested that the various educational systems incorporate the musical preferences of the students in their different levels of curricular concretion so that their identities are recognized in the classroom. At the same time, this implies carrying out a series of educational reforms, including teacher training to help them understand the complexity of the construction of these preferences and to modify the traditional forms of music teaching-learning that take place in, generally academic, educational centers. Likewise, the musical preferences of the students cannot be conceived as a closed repertoire that can be prescribed, nor can they be reduced to a historical canon of pieces belonging to UPM, but which no longer have anything to do with the present identities. In this sense, it will be necessary to use methodologies that find out these changing identities from the educational practice itself, through participatory proposals and joint choice of the repertoire. In this way, the incorporation of the musical preferences of students in the music classroom could constitute a form of democratic education and contribute, through curricular negotiation and egalitarian dialogue, to the development of civic and civilian competencies.

5. REFERENCES

AUTORES:

Pablo Marín-Liébana

Personal investigador del Departamento de Didáctica de la Expresión Musical, Plástica y Corporal en la Facultad de Magisterio de la Universitat de València. Es Diplomado en Educación Social, Grado en Maestro en Educación Primaria y Máster en Investigación en Didácticas Específicas por la Universitat de València, Licenciado en Historia y Ciencias de la Música por la Universidad de la Rioja, Máster en Memoria y Crítica de La Educación por la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia y Grado Profesional en Guitarra por el Taller de Música Jove de Valencia. Su actividad investigadora se centra en el desarrollo de recursos audiovisuales para favorecer los procesos de escucha, el análisis de libros de texto y la didáctica musical crítica.

Pablo.Marin-Liebana@uv.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2326-1695

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pablo_Marin-Liebana

José Salvador Blasco Magraner

José Salvador Blasco Magraner es Doctor en Ciencias Sociales y Humanas y Licenciado en Historia y Ciencias de la Música por la Universidad Católica de Valencia. Recibió el Premio Extraordinario de Doctorado por su tesis titulada “Vicente Peydró Díez: vida y obra”. Es también Licenciado en Dirección de orquesta por la prestigiosa Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music de Londres y Diplomado en Didáctica de la lengua inglesa por la Universitat de València. Asimismo, es Editor de CABA y de la editorial Sociedad Latina de Comunicación Social. Es autor de nueve libros y más de cincuenta artículos en revistas nacionales e internacionales. En la actualidad es Profesor Ayudante Doctor del Departamento de Didáctica de la Expresión Musical, Plástica y Corporal de la Facultad de Magisterio de la Universitat de València.

j.salvador.blasco@uv.es

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8937-5842

Ana Marín Botella Nicolás

Profesora Titular del Departamento de Didáctica de la Expresión Musical, Plástica y Corporal de la Facultad de Magisterio de la Universitat de València. Doctora en pedagogía por la Universitat de València. Es Licenciada en Geografía e Historia, especialidad Musicología y maestra en Educación Musical, por la Universidad de Oviedo. Grado profesional en la especialidad de piano y Máster internacional en la misma especialidad. Durante el año 2001, toma plaza en el cuerpo de profesores de música de enseñanza secundaria en Alicante. Forma parte de la Comisión de Coordinación Académica del Master Universitario en Profesor/a de enseñanza secundaria de la Universitat de València. Ha sido directora del Máster en Investigación en didácticas específicas. Coordina el doctorado en la especialidad de música de la Facultad de Magisteri. Ha sido directora del Aula de Música del Vicerrectorado de Cultura e Igualdad de la UVEG. Es Vicedecana de la Facultad de Magisterio.

Ana.Maria.Botella@uv.es

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5324-7152

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=AEq28xAAAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ana_Botella_Nicolas

Academia.edu: https://uv.academia.edu/ABotellaNicol%C3%A1s

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ana_Botella_Nicolas

Academia.edu: https://uv.academia.edu/ABotellaNicol%C3%A1s