Source: authors’ own creation.

doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.154.e1277

RESEARCH

MIGRANT UNIVERSITY PROFESSORS: A QUANTITATIVE LOOK AT A QUALITATIVE PROBLEM

DOCENTES UNIVERSITARIOS MIGRANTES: UNA MIRADA CUANTITATIVA A UN PROBLEMA CUALITATIVO

PROFESSORES UNIVERSITÁRIOS MIGRANTES: UM OLHAR QUANTITATIVO A UM PROBLEMA QUALITATIVO

Audy Salcedo1

Ramón Alexander Uzcátegui Pacheco .

1Central University of Venezuela. Venezuela.

1Andrés Bello National University. Chile.

[1] He holds a Degree in Education and a Ph.D. in Humanities. He is a Professor at the Andrés Bello National University, Chile.

ABSTRACT

Concerning Venezuela, migration is a recent phenomenon that, due to its magnitude, has attracted the attention of countries and international organizations. This study focuses on university professors to investigate some of the factors that conditioned their leaving the country, determine their job and academic characteristics at the time of migration, and explore elements of their social inclusion and professional integration in the host country. We worked with a non-probability sample of 373 professors who answered an online questionnaire. The results indicate that the country's economic and political crisis motivated their migration. Most began to leave as of 2015. Almost half hold a doctorate and less than a third now work in university teaching, but they state that their living conditions are better now than when they migrated.

KEY WORDS: Professorship, Diaspora, Higher Education, Academic Career, Venezuela.

RESUMEN

Para Venezuela la migración es un fenómeno reciente que por su cuantía ha llamado la atención de países y organismos internacionales. Este estudio se centra en docentes universitarios para indagar algunos de los factores que condicionaron su salida del país, determinar sus características laborales y académicas al momento de la migración y explorar elementos de su inserción socio profesional en el país receptor. Se trabajó con una muestra no probabilística de 373 docentes que respondieron un cuestionario en línea. Los resultados indican que la crisis política económica del país motivó su migración. La mayoría salió a partir de 2015. Casi la mitad tiene título de doctor y menos de un tercio trabaja ahora en docencia universitaria, pero señalan que sus condiciones de vida son mejores a las tenían al momento de migrar.

PALABRAS CLAVES: Profesorado, Diáspora, Educación Superior, Carrera Académica, Venezuela.

RESUMO

Para Venezuela a migração é um fenômeno recente que pela sua quantidade tem chamado a atenção de países e organismos internacionais. Este estudo está focado nos professores universitários e para procurar alguns dos fatores que condicionaram a sua saída do país, determinar as características dos seus trabalhos e acadêmicas no momento da migração e analisar elementos da sua inserção sócio profissional no país receptor. Foi realizada uma amostra não probabilística de 373 professores que responderam um questionário on-line. Os resultados indicam que a crise política e econômica do país motivou sua migração. A maioria saiu a partir de 2015. Quase a metade tem doutorado e menos de um terço trabalha agora como professor universitário, mas apontam que suas condições de vida são melhores do que as que tinham no momento de migrar.

PALAVRAS CHAVES: Professores, Diáspora, Educação Superior, Carreira Acadêmica, Venezuela.

Correspondence:

Audy Salcedo. Central University of Venezuela. Venezuela. audy.salcedo@ucv.ve

Ramón Alexander Uzcátegui Pacheco. Andrés Bello National University. Chile.

razktgui@gmail.com

Received: 14/09/2020.

Accepted: 12/12/2021.

Published: 12/03/2021.

How to cite this article:

Salcedo, A. y Uzcátegui Pacheco, R. A. (2021). Migrant university teachers: a quantitative look at a qualitative problem. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 154, 101-131. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.154.e1277

http://www.vivatacademia.net/index.php/vivat/article/view/1277

Translation by Carlos Javier Rivas Quintero (University of the Andes, Mérida, Venezuela).

1. INTRODUCTION

Venezuela has become a migrant producer country. Reports from the United Nations (UN), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) indicate that it is a massive phenomenon. The United Nations High Commissioners for Refugees (UNHCR, 2019) claims that there are more than 4.7 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants throughout the world and more than 750,000 Venezuelans have requested asylum in different countries. Only these figures are sufficient for the Venezuelan migration issue to constitute a challenge for the region.

The humanitarian crisis, and, in general, the deterioration in the republican democratic institutions, has reached such levels that part of the population has decided to leave the country to seek better living conditions. The crisis induced by the idea of re-founding the republic and insisting on establishing the 21st century socialism have seriously affected the country in all areas, and have damaged all social institutions, namely, the institutions of the education system; university professors, who are, in this case, the subject of our research.

The studies about Venezuelan migration have been arousing concern in the academic world, such as those developed by Osos and Villares, (2005); Mateo and Ledezma, (2006); Rivas, 2009; Echeverry Hernández, (2011); Castillo Crasto and Reguant Álvarez, (2017). Regarding professional migration, it is important to bear in mind the works of De la Vega, (2003); Ibarra Lampe and Rodríguez, (2011); De la Vega and Vargas, (2014); Páez (2010); Zuñiga (2011); Requena and Caputo (2016); and Vargas Ribas (2018), García Arias and Restrepo Pineda, (2019) who have been characterizing the problem in different working fields. On this basis, our research focuses on the study of university professors, as a migrant population, to define their personal characteristics, to know why they decided to migrate, and based on their own opinions, to have an idea about their academic life beyond Venezuela’s borders. Have their living conditions improved? Have they been able to continue their academic career in the host countries? It is part of what is addressed in this research work.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The IOM defines international migration as the movement of persons who leave their birth country or place of usual residence to settle temporarily or permanently in a country of which they are not nationals. To get a better idea of this, “The number of international migrants increased from 93 million in 1960 to 258 million in 2017” (UNESCO, 2019, p. 35). A characteristic of international migration in recent years is the ease of mobilization (Cabieses, Bernales & McIntyre, 2017) and the complexity of the causes behind it.

International migration can have various causes “There are 87 million displaced people around the world: 25 million refugees, 3 million asylum-seekers, 40 million internally displaced due to conflicts and 19 million due to natural disasters” (UNESCO, 2019). Today, migratory flows reconfigure the global scene, the north-south human displacements are now south-south, as in the case of the Latin American region, where a large portion of the population is no longer migrating to the historically traditional destinations such as the United States or Europe; instead, they are moving within the subcontinent seeking better life options among the neighboring countries.

Venezuela is a case of forced migration, the situation to which the population has been subjected as a result of government action has forced millions of people to leave their homes and move toward other countries. The loss of quality of life, institutional dissolution, and systematic violation of the human rights enshrined in the Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, adopted in 1999, determine the reasons why many Venezuelans leave their country. Migration “can never be considered completely voluntary” (Davidson, 2003, p. 37). In the Venezuelan case, there is a combination of structural and individual variables, with the former being a determining factor behind this migration process (Ibarra Lampe & Rodríguez, 2011). Venezuela appears in the statistics of countries affected by attacks made on education, military use of facilities, or students or education personnel being harmed, as per the 2018 GCPEA report, Education Under Attack (cited by UNESCO, 2019, p. 201), this data matches with other indexes in which the country stands among the first positions regarding inflation, insecurity, food security, health, etc.; as long as the crisis worsens, the number of people fleeing Venezuela will only increase (Mahlke & Yamamoto, 2017); there is no reason to believe that the number of Venezuelans leaving their country will decrease in the foreseeable future (Feline Freier & Parent, 2019).

The migration process subject of our study is a high skilled migration, understood as the flow of persons moving from one country into another who have completed tertiary education equivalent to a bachelor’s degree (OIM, 2018, p. 51). Although these criteria may vary; since, as pointed out by IOM, in addition to education, other variables such as the type of job performed or the position in the employment structure in the country of origin can be taken into account. Skilled migration is not a new phenomenon (Baeninger & Jarochinski, 2018, p. 335); many governments around the world have designed policies to host, according to their areas of interest and development needs, talents from other societies. Skilled migration could derive more from a selective logic -needs for human talent, labor market, etc. - than from the current Venezuelan migratory pattern by which there is a massive outflow of citizens, many of them as refugees or displaced persons.

The high qualifications that refugees, displaced people, and migrants have are not immediately perceived, acknowledged or validated in the host country. The professional insertion and development process of the immigrating human group may be limited by legal, language, cultural, and certification barriers. For people, “limiting recognition of their qualifications is a further impediment, which immigrants often rate above language skills as a challenge” (Eurostat, 2014, quoted by UNESCO, 2019, p. 103). This represents a challenge for migrants with high education levels or who carry out university work. This situation has a direct impact on the person, their self-esteem, and their employability in the host countries, “Over one-third of immigrants with tertiary education in countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are overqualified for their jobs, compared with one-quarter of natives (OECD/European Union, 2015; cited by UNESCO, 2019, p.103).

Venezuela’s skilled migration is a phenomenon that also occurred in the 1990s and 2000s; the difference between now and then is that, instead of being a selection process for professionals, it is a massive general outflow phenomenon of people. The most commonly mentioned causes are “the tremendous differences in the quality of life and the working conditions for professionals’ performance” (Requena & Caputo, 2016, p. 445). Today, it is associated to the overall crisis of Venezuelan institutions, to the point of being considered a humanitarian crisis.

The Venezuelan case is not exactly a brain drain, but rather a brain expulsion considering how the country’s public affairs, the management of the university system, and the science and technology development model have been handled. Until 1999, the number of Venezuelans who had been entering the research system was higher than those leaving from it, as of 2000 “that situation changed and the net flow became negative” (Requena & Caputo, 2016, p. 449). Certainly, this outflow represents the emptying of Venezuelan institutions (Uzcátegui, Guzmán & Bravo, 2018), thus hindering the capacity of their creative forces, “skilled migration negatively impacts the home country in different ways, including economic growth, international trade, investment in education, tax contributions, and knowledge and technology transfer” (Abella, 2006, cited by OIM, 2018, p. 43). This situation can be reversed if international experience is capitalized on to strengthen skills in the home country, “These experiences and contacts are very valuable resources for skilled migrant’s home country, as long as the opportunities for them to implement their abilities there exist” (Arocena & Sutz, 2006 cited by OIM, 2018, p. 44).

University professors are part of the skilled migration that has left Venezuela over the past years; their academic career was interrupted. The academic career was part of the modernization process of Venezuelan universities in the 20th century (Parra Sandoval, 2003). By Universities Act, the teaching staff are not only knowledge transmitters, but also knowledge creators (Morles, Medina & Álvarez, 2003), their stage are higher education institutions. The possibility of exclusive and full-time dedication to teaching, in addition to research and extension, is part of the strategy to strengthen not only the university, but also the Venezuelan system through the creation of knowledge, research, and innovation.

In 2014, a migratory movement from the university sector started to be strongly perceived. The director of the Professors Association of the Central University of Venezuela, Gregorio Alfonzo, counted 834 resignations from 2008 to 2011, “This year, 11 Doctors of the Faculty of Science migrated, the exodus of professors could reach 220 in 2014” (Méndez, 2014, El Universal); “The better salaries and conditions that countries such as Ecuador, Colombia, Mexico, Chile and Brazil offer have further exacerbated the situation of thousands of professors migrating” (Méndez, 2014, El Universal). The representative of the Professors association, Tulio Olmos, states that “Professors want to live decently and universities do not guarantee that” (Méndez, 2014, El Universal). This situation not only concerns university professors, since the number of primary and secondary education teachers fleeing the country is increasing (Montilla, 2014, December 8).

Since 2007, the Venezuelan government has maintained the same national budget for universities. Every year, each university sends a budget according to its different needs, but the Venezuelan government rejects it and allocates the same amount as in 2007, which is called redirected budgets. To close the budget gap of every year, universities depend on the so-called additional credits, unilateral allocations of extra amounts given by the government. These additional credits are allocated several times a year, but without any planning. This dynamic does not correspond either to the institutional dynamic of universities or to the country’s macroeconomic situation, which has been affected by a three-digit chronic inflation per year. In 2020, Benjamín Scharifker, rector of the Metropolitan University, pointed out that “students and professors’ desertion is around 40%, on average” (Descifrado.com, 2020, March 8), which represents a true exodus of talented people in the sector.

The forced nature of the Venezuelan migration can be observed in the reports prepared by official organizations dedicated to address this issue. For example, the Brazilian Federal Subcommittee for Integration of immigrants indicated that 27% of the men who arrive in the country do it to seek shelter or refuge, and 9% of the male population do it to search for a job. The report indicates that a significant proportion of Venezuelans (83%) travels together with their family, which signifies an important number of people mobilizing toward the neighboring country (ONU-Migración, 2019). From 2013 to December 2019, “264,000 Venezuelans have requested asylum or residence in Brazil, with most of them entering through Roraima” (Fundação Getulio Vargas - FGV, 2020). As the report points out “This flow is unprecedented in regional terms due to the significant number of people who ‘are migrating’ at this time throughout the South American region seeking to survive” (FVG, 2020: 23). These figures in Brazil are just part of the problem; according to the Refugee and Migrant Response Plan platform (RMRP) “As of October, 2019, more than 4.5 million refugees and migrants from Venezuela are outside their country of origin, with 3.7 million in the region alone” (RMRP, 2020). It is estimated that the number of migrants from Venezuela will reach up to 5.5 million by the end of 2020 (RMRP, 2020).

The first waves of Venezuelan migrants traveled to the United States and Europe, but there has been a change in the migratory pattern over the past recent years; a significant increase in migrants moving to South America. Venezuelans’ distribution across the region has impacted Latin American societies. In 2017, “Colombia accounted for about 600,000 Venezuelan migrants, and in Central America and the Caribbean, the number of Venezuelan nationals increased from around 50,000 in 2015 to almost 100,000 today” (OIM, 2019, p. 3). By December 2018, Chile reported that Venezuelans were the largest group of immigrants in the country; out of 1,251,225 foreigners, 23% were Venezuelans; at that time, the figure amounted to 288,233 Venezuelans established in the southern country (INE, 2019). Until December 2019, the distribution of Venezuelans in the subcontinent was as follows: Colombia 1,600,000, Ecuador 385,000, Peru 863,600, Chile 371,200, Brazil 224,100, Argentina 145,000, Uruguay 13,700, and Paraguay 3,800. In Central America and Mexico: Panama 94,600; Mexico 71,500; Costa Rica 28,900 (R4V, 2019). International entities estimate that this phenomenon will not be reversed in 2020, but will rather intensify.

3. METHODOLOGY

From a methodological perspective, this is a descriptive and field research, carried out by using the survey technique. To that end, we designed a semi-structured questionnaire, comprised of open-ended and closed-ended questions. Quantitative and qualitative parameters were used for data processing; hence, this can be considered a mixed research, which aims to identify the personal and academic characteristics of a sample made up of university professors; the reasons why they decided to leave Venezuela.

This research was conducted in a loose way regarding time in order to achieve its objectives. This entailed documentary review, reading reports, and press consultations to understand properly the background of the topic in question. Venezuelan migration has become a research subject for different groups and universities in the region. This first review brought us closer to our specific subject of analysis: university professors. This decision was made on the grounds of the public concern noted due to the emptying of educational institutions, namely, the migration of teachers and professors in the different ranks of the Venezuelan education system.

We designed a 56-question survey; some are multiple choice questions and others are open-ended, hence respondents could provide their thoughts on the issue at hand. The following variables were considered: identification of the professor, affective-family aspects, employment situation before and after leaving their country; their academic career status, decision or option to migrate, migration process, and ties with Venezuela. Based on this, we aim to delve into some of the factors that conditioned their leaving the country, determine their employment and academic characteristics at the time of migrating, and explore elements of their social inclusion and professional integration in the host country.

The processing of the closed-ended questions was quantitative, in order to determine representative frequencies and percentages of the statements proposed. The open-ended questions were processed qualitatively, they were addressed based on the analysis of critical ideas; hence, we read each one of the statements made by the respondents. The answers, meaning the phrases provided by the people surveyed, were grouped and organized into answer clusters to which descriptors were assigned; keywords that were later conceptualized as categories of analysis. These categories were deduced from the answers given by the respondents. This categorization process entailed reading, selecting the frequencies, and organizing the sentences to arrange them in substantive paragraphs for the investigation. Based on these groupings, we identified the ideas, propositions, and conceptualizations that, from the perspective of migrant professors, help characterize their conditions and the situation of universities, the host country, and Venezuela.

The questionnaire was validated by 5 specialists in these subjects and also by 5 methodologists. Once they expressed their opinions, small modifications were made to adjust the questionnaire. The instrument was designed and administered via a virtual platform; it was available for three months, and professors were invited to participate during that time. This format guaranteed no information duplication, since participants answered it using their emails; it also facilitated contact with informants in many different locations.

We used the snowball sampling approach, a non-probability sampling technique that is frequently used by researchers to get access to low-incidence populations and hard-to-reach individuals. After identifying the first subjects, they were asked to help locate other people with a similar profile. In this case, the starting point was a list of emails of professors who we knew had migrated, thus the link to the questionnaire was sent to them together with an informed consent form to participate in the research, explaining its objectives, as well as their rights and responsibilities as possible participants; in addition to guaranteeing confidentiality of the data obtained and its exclusive use for the research. After answering the questionnaire, the participants were asked to suggest names and email addresses of other professors who they knew for certain had migrated. Additionally, they were asked to invite colleagues to answer it, given their condition of migrants.

The application used delivers a timestamp; a record of the time and date during which each questionnaire was answered. This permitted monitoring the start and end times of the data collection process. From August to October 2018, 373 fully answered questionnaires were collected. The sample was made up of 50% women, with ages ranging from 25 to 81 years. 71% of the people surveyed are married. Regarding the collected information, we proceeded to conduct a first descriptive analysis, which, as we pointed out at the beginning of this article, would allow us to determine the characteristics of the Venezuelan migrant professors who participated in our research.

4.1. Personal characteristics

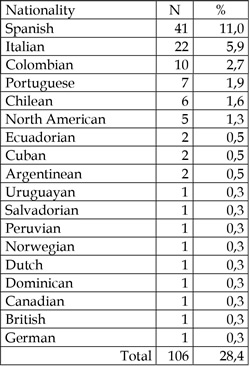

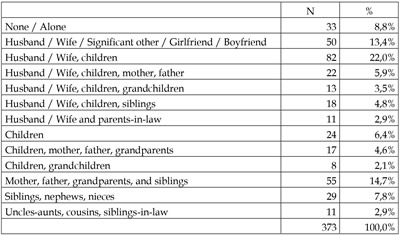

Their nationality was the first aspect queried. 100% claimed that they were Venezuelans, almost all by birth. Only 8 people indicated to be Venezuelans but that were born in another country, which means it was their second nationality. Table 1 shows the nationality distribution of 28.4% of the people who stated having a second nationality, different from Venezuelan.

Table 1. Second Nationality.

Source: authors’ own creation.

The four most prominent nationalities are: Spanish, Italian, Colombian and Portuguese; all traditionally welcomed nationalities when Venezuela was a host country to migrants. In the 1950s and 1960s, the arrival of Spaniards, Italians and Portuguese migrants was common in Venezuelan. In the 1970s, large waves of Colombian migrants arrived, attracted by the country’s economic conditions and fleeing from the difficult situation that Colombia was experiencing due to the activity of guerrilla groups. In those years, Venezuela was also host to migrants fleeing dictatorships of the southern cone. In studies about migration, knowing whether migrant persons have a second nationality is relevant since it is a measure to know historical and recent migratory flows. Regarding this aspect, 71.4% claimed only having the Venezuelan nationality, which signifies that they are probably migrants for the first time, and that they probably, or potentially, will attain a second nationality in the course of their lives, thus expanding the exercise of citizenship in the host countries. Chart 1 shows the distribution of ages of the group under analysis.

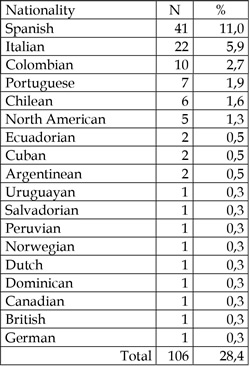

Source: authors’ own creation.

Chart 1. Ages of migrant professors.

The group is predominantly young; 68.6% stated that they were 55 years old or younger. In general, we are in the presence of a sample comprised of working-age university professors, who are still fully capable of developing their academic careers. Venezuelan migrants represent a young population segment with potential for further development that will possibly join the professional and university systems in the host or receiving countries.

Regarding their home city, 63.8% stated that they lived in the so-called Greater Caracas (Caracas and adjacent cities). In the Venezuela of that time, this meant better public services, higher supply rates for food and medicines, but also higher rates of personal insecurity.

4.2. Socio-affective aspects of migrant university professors

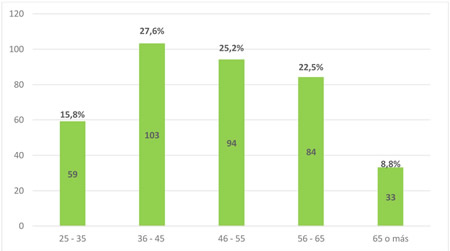

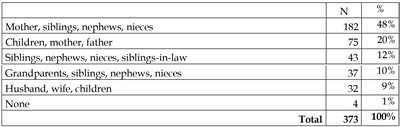

In the research, we deemed it relevant to ask the migrant university professors about their socio-affective situation, both when leaving Venezuela and in the host country. This section included various items, one of them queried about which family members were currently with them in the host country. The answers were varied, since respondents were given the opportunity of listing all the relatives who were living with them. The list of relatives included was varied, ranging from wife and children, through siblings-in-law and nephews, to parents, grandparents, and grandchildren. Table 2 shows the categories elaborated to group the different family members listed by the participants.

Table 2. Family members currently living with them.

Source: authors’ own creation.

The most prominent aspect is that the professors surveyed did not migrate alone, most of them left with one or more close relatives. Less than 10% stated that they were alone in the host country. More than 50% claimed that they were living with a significant other or spouse and another relative; with the group of direct relatives “Husband / Wife and children” standing out. A little more than 20% said that they were living with their parents in the country to which they migrated. These results coincide with what Cohen (2001) had pointed out, that migrants tend to involve a relative or a fellow countryman or woman.

A second item, related to the affective situation of university professors, is to know with which members of their family group they are not currently living. Among the responses, many stated that a large proportion of their relatives were in Venezuela, while others had already migrated to other countries. The fact that most of the professors are not currently living with their parents stands out among the answers; one group claimed that they were not living with a significant other or children. These are migrants who are not living with part of their closest relatives. In the answers provided, the professors also indicated that they were far from their grandparents, grandchildren, nephews, nieces, siblings, siblings-in-law, etc. Having part of their family in Venezuela could generate worries for these migrants, given the country’s political, economic, and social situation.

Table 3. Family members with which they are not currently living.

Source: authors’ own creation.

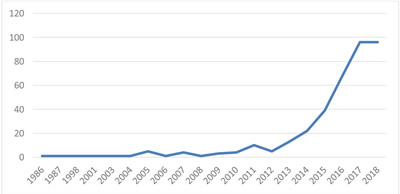

4.3. Migratory flow of Venezuelan university professors

How has the migratory flow of university professors been? This is a relevant aspect for our research since it allows us to characterize: the time that has elapsed since they left Venezuela, the countries to which they have migrated, the means of transportation they used to migrate and their current living space. In this regard, when professors were asked about the date they left Venezuela, there were some extreme cases of people who left the country in 1986 and 1998. Except for these cases, the sample is evidence of the trend that has characterized the Venezuelan migratory dynamic in recent years. With important outflow peaks being registered in 2005, 2007, and 2011, years during which important events occurred regarding the Venezuelan sociopolitical dynamic. The trend was steady, but became a steep upward trend as of 2012, with an exponential increase ever since. In October of that year, Hugo Chávez Frías won the presidency of the republic again, although with serious allegations of fraud. The following year, the death of President Chávez was disclosed and new elections were held, in which the candidate of the ruling party, Nicolás Maduro, was proclaimed winner, but once again, with allegations of fraud. As of this point, the largest waves of Venezuelan university migration ever seen began.

Out of the 373 people surveyed, 299 left the country between 2015 and 2018, the year when this information was collected. This coincides with the worsening of the university crisis, the student demonstrations, the humanitarian crisis, and the breach of the rule of law due to the call for a Constituent Assembly (still operating) and the re-election (through questionable mechanisms and results) of Nicolás Maduro for a new presidential term.

Source: authors’ own creation.

Chart 2. Year they left Venezuela.

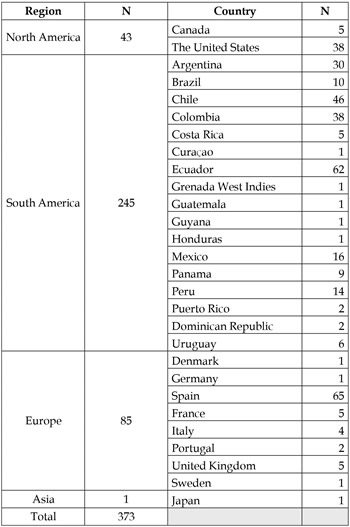

Where have university professors migrated to? This is an important aspect for our investigation since it describes the movements followed by the professionals. The information collected demonstrates that the pattern followed is the same that has predominated in recent years regarding the Venezuelan issue; migration toward the south of the continent. Table 4 shows the migratory flow of the destinations chosen.

Table 4. Destination country.

Source: authors’ own creation.

Regarding the migrants comprising this sample, Spain and Ecuador are the countries with the highest reception rates. The former could be explained by family ties, while the latter could be due to the Prometheus Project in that country, which offered high salaries compared to the low earnings Venezuelan professors received. Other countries that stand out are Chile, Colombia, the United States and Argentina. The main destination countries of this sample coincide with the countries that Venezuelans consider as preferred to migrate to (Consultores 21, 2019).

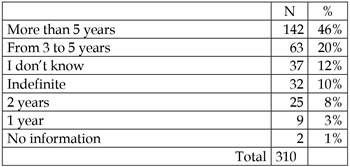

They were asked how long they estimated to stay in the host country. 310 valid results were obtained, and a series of comments that, in some way, express professors’ projections for their stay in the host country and the future situation in Venezuela. Table 5 collects the responses categorized.

Table 5. Estimated time in the host country.

Source: authors’ own creation.

More than half the group stated that they could stay, for at least, three years. The length of stay tends to be inversely proportional to the chances of returning. A longer stay signifies more possibilities of settling in the host country, thus lowering the chances of returning to Venezuela.

Regarding the reasons that would cause professors to stay longer in the host country, the responses were varied, but how changes in Venezuela are perceived stood out. Emphasis is placed on the changes they may observe in Venezuelan society and their perception that such changes could signify an improvement that would make their returning feasible. According to Dumont and Spielvogel (2008), return migration encompasses four dimensions: country of origin, place of residence abroad, duration of stay in the host country, and duration of stay in the country of origin after returning. The answers provided involve three of these dimensions, thus leaving the possibility of returning open.

According to the perspective of the Venezuelans who are still in their country, their fellow countrymen and women will only return if the situation changes (45%), but 35% consider that they will not return (Consultores 21, 2019). Thus, the issue of estimating the length of stay in the host country, rather than being a chronological time issue, it is more related to Venezuela’s socio-historical timing: its political evolution and their perception that the conditions for which they decided to leave would improve.

4.4. To migrate: an option for Venezuelan university professors

The crisis situation that Venezuelan society is facing has forced many of its citizens to make the decision to migrate. The possibility of exploring better conditions than those under which the Caribbean country is, led many of its professionals, and particularly, migrant professors, to undertake new life plans abroad. The situation has already become a real challenge for the region, since this migration process has had different waves, faces, and impacts on the host countries. According to OECD (2019), the countries with the highest number of migrants are Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq and Venezuela, which places Venezuela in fourth place worldwide. Furthermore, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR, 2019) states that the exodus of Venezuelans is the largest in South America’s recent history.

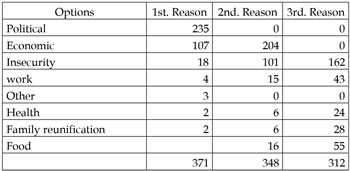

In this context of diaspora, knowing the reasons why they decided to leave the country is a relevant detail, as well as to know what aspects are related to that decision. Professors were asked to mark three reasons why they had decided to leave Venezuela, the options were: political; economic; insecurity; food; work; health; family reunification; and others, in which they had to specify the reason that forced them to migrate. The results are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Reasons why they decided to migrate.

Source: authors’ own creation.

As it can be noted, three reasons stand out among the ones indicated by the professors: political, economic, and insecurity reasons, placing the emphasis on the country’s general political situation; the main reason for their leaving. The fourth option was their working situation at the university, which of course, was heavily influenced by the previous variables.

Escaping from conflict zones is one of the oldest and most common causes of migration. This also applies to the Venezuelan case. As aforementioned, these data were collected in mid-2018; Venezuelans had endured a 2017 with more than three months of protests and about 120 citizens were murdered during those demonstrations. Furthermore, that same year, the Government of Nicolás Maduro promoted the Constituent National Assembly with the possibility of drafting a new constitution. All this contributed to a political climate of instability that, combined with personal insecurity (third reason), resulted in a country in permanent conflict, which can be considered a conflict zone. It is any person’s need to be in safer environments, far away from what is considered, in this case, political and personal violence.

Economic reasons appeared as the second most checked aspect (in the first reason list) to leave the country, but it was also the most frequently chosen reason in the second place, which demonstrates its importance as a major migration factor. Economy is another traditional reason for migration in the world; seeking better income that will allow them to improve their lives. At the time of collecting the data, in addition to low salaries and the collapse of public services, the country was experiencing a high inflation rate, and food and medicine shortages. This situation has not changed much, and according to the 2019 Bloomberg Misery Index, Venezuela was the country with the worst combination of unemployment and inflation rates -more than 8,000,000%- in the world (Jamrisko & Saraiva, 2019), which gives us an idea of the serious situation in the country. In February 2020, the Central Bank of Venezuela released economic figures once again (it had not published them since 2016) and acknowledged an inflation of 9,585%, higher than that announced by the National Assembly (where the opposition holds the majority) for the same period: 7,374%. Regardless of the differences and possible doubt about the official figures, Venezuela still has the highest inflation rate in the world and continues to be in hyperinflation; therefore, sufficient grounds to migrate.

The reasons why they decided to migrate were related to family: “Health conditions of my mother”; “Health conditions of my mother abroad”; “To help my grandchildren leave the country”; life and family project: “To take care of my grandchildren”; “To start a new life cycle”; “Deterioration in the Quality of Life and fundamental principles”; “I had a baby when I was abroad and I did not come back”; “In order to think about having children we had to leave”; “Venezuela is not a place to educate young children”; “My husband wants to migrate”; “Instability for my future”; sentimental reasons: “I started a sentimental relationship with a foreigner and his country offered better conditions for both of us at that time”. The list of reasons is longer, as stated by the people surveyed.

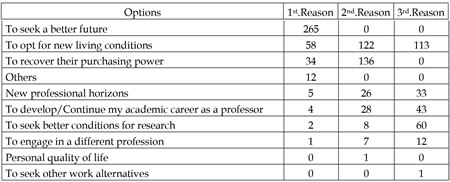

When asked directly about the reasons connected to their decision to migrate, they stated:

Table 7. Their decision to migrate.

Source: authors’ own creation.

When asked to specify the reasons behind their migration, the group surveyed indicated as the main ones: To seek a better future, to recover their purchasing power, and to opt for new living conditions. All of them are related to the ones mentioned in the previous question: political, economic, insecurity, and work reasons. Migrating is a beacon of hope for migrants and their families to find better economic conditions, which represent higher living standards (Stark & Taylor, 1991; Izcara, 2010).

4.5. Academic career

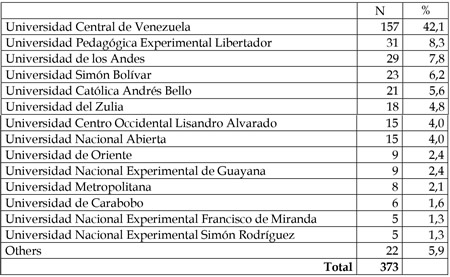

Venezuelan university professors are professionals who have devoted themselves to teaching, research, and extension in the context of higher education institutions. As professionals, they fulfill the requirements that define an academic career, established in the Universities Act, the Actas Convenio [EN: Agreements], and the rules and regulatory statutes that order the academic life of Universities. So far, we have characterized the migration process of university professors. In this section, the academic particularities of the professors who migrated are addressed, namely: in which university they worked, what was their educational level when they left the country, activities conducted, time devoted to the university, and the research work conducted by them.

The sample was made up of professors from more than 14 universities, most of them public universities (89%), with a significant bias of professors who worked at the Central University of Venezuela (42.1%).

Table 8. University in which they worked.

Source: authors’ own creation.

The university crisis derived from the lack of budget, low salaries, and deterioration of institutional conditions are aspects that determined that most of the professors surveyed came from public universities (autonomous and experimental). As aforementioned, Venezuelan universities have had the same budget since 2007, changes in this regard are made unilaterally by the national government and more than 90% of what is allocated is used to pay personnel salaries. Budgetary allocations for research are exiguous or symbolic. All this makes the teaching and research labor difficult. Salary increases are also decided unilaterally by the executive or through arrangements with unions linked to the government. In addition to this, there is also the fact that autonomous universities had their elections for authorities suspended by decision of the Supreme Court of Justice since 2011. Therefore, in addition to the nationwide conflict climate, there is also the deterioration of the working conditions and operation of institutions; all this creates the conditions to undertake a new life project outside the university and the country.

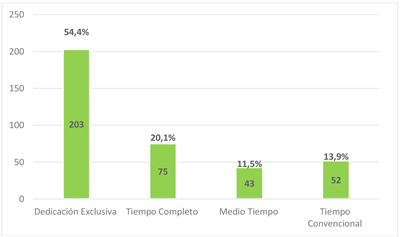

Only 18% of the respondents indicated that they were tenure track professors, meaning that most of them were tenured university staff; universities were counting on this group of professionals to carry out the teaching and research work in the coming years. This delicate situation worsens after evaluating the time they devoted to the institutions for which they worked.

Source: authors’ own creation.

Chart 3. Time devoted to universities.

Most of the subjects in the sample claimed that they were professors under an exclusive contract with their university: these are professors who devoted 40 hours per week to the university, and, according to current regulations, they can only work with just one higher education institution. If we add the ones who stated that were full-time professors, it means that more than 74% of the professor who migrated devoted at least 36 hours per week to their universities. This signifies losing more than 10,000 weekly hours of activity between these two groups of professors combined. A significant loss for Venezuelan universities regarding the teaching staff that devoted the most amount of time, in accordance with the regulatory conditions established in the matter.

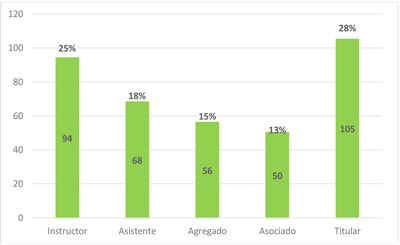

Regarding the academic development achieved at the time of leaving the country, the majority indicated that they were in the rank of Full Professor, the highest position in the hierarchy of an academic career in Venezuela. According to their answers, the distribution is as follows:

Source: authors’ own creation.

Chart 4. Rank in the university academic hierarchy.

Although the majority stated that they were in the rank of Full Professor, there is another group with a similar number that claimed that they were in the rank of Instructor, which means that both a portion of professors that were starting their academic career and a portion that were finishing it left the country. The former probably had at least twenty three years of university service left (Instructors), and Full Professors five years or less; a possible decrease in years of service for Venezuelan universities.

If we combine the professors in the rank of Instructors with those in the following level (Assistant), there is a 43% decline in the number of next generation university professors. If we take into account that, by regulations, in order to qualify for the Full Professor category it is necessary to have been working in the university for at least 15 years, this is a group of professors who had the possibility of attaining that last rank in their academic career; as long as they fulfilled the personal, institutional, and social conditions to accomplish it.

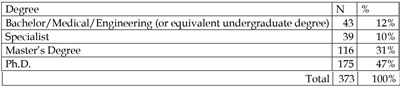

When inquiring about their level of education attained by the time they left the country, most of the respondents indicated that they hold a Ph.D. Table 9 shows the distribution of the education level attained based on the information provided by the group.

Table 9. Education level attained by the time of leaving Venezuela.

Source: authors’ own creation.

Table 9 shows that 78% of the respondents hold at least a Master's degree. Their leaving the country represents a significant loss of years of training invested by Venezuelan universities, which will have negative effects on students and lower-rank professors who would later serve as educators.

We asked these professors about their years of service at their institution by the time they left the country. According to what they have indicated, Venezuelan universities have lost 5,878 years of teaching and research experience, which is the sum of all the years of service in the group combined. On average, it means 15.51 years of experience per professor, with a standard deviation of 11.02, which signifies that it is a quite heterogeneous group based on their teaching experience. Taking this information into account and on the basis of Venezuelan legislation, which states that a university professor can retire after 25 years of service, we have excluded the cases of professors who had 24 years or more working at their institution and calculated the time remaining for them to be entitled to retirement. The results are shown in Chart 5.

Source: authors’ own creation.

Chart 5. Years of service in the university.

This group accumulated 2,532 years of experience with a mean of 9.7 years per professor and a standard deviation of 6.11 years. Regarding the time remaining for retirement, 75% of them still had from 9 to 24 years of service left before being eligible for this right, while 50% had from 14 to 24 years left. Based on the average of years of service and the time remaining for retirement, this group seems to be comprised of professors who had just started or had partially advanced in their academic careers; it is a portion of the professors who would later be in the front lines of teaching and research in their universities. All of them accumulate a total of 3,993 years of possible service at Venezuelan universities, with a mean of 15.3 years per professor and a standard deviation of 6.11 years. All these numbers suggest a significant loss of years of teaching and research, and an even greater loss considering the years that this group could have devoted to working in Venezuelan universities.

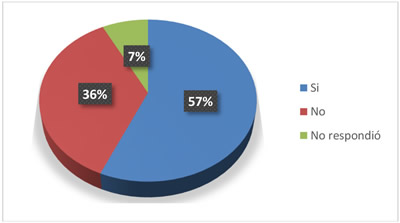

The participants were also asked if they had taken part in lines of research or research groups at the university where they worked. The majority indicated that they had lines of research and took part in research groups.

Source: authors’ own creation.

Chart 6. Activity with lines of research by the time they migrated.

According to what respondents have stated, most of these lines of research were discontinued when they left the country, which would probably represent a substantive decrease in the research and innovation capacity of Venezuelan universities, as well as a decline in the number of articles being published. Van Noorden (2014) points out that Venezuela is the only South American country whose scientific production has been decreasing, since the number of citable publications declined by 29% from 2009 to 2013. When examining the Latin American countries with the highest scientific production rates in the SCImago Journal & Country Rank (SCIMAGO LAB, 2018), we found that Venezuela went from being in the fifth place in 1999 to the tenth in 2018. In 1999, Peru’s production rates represented 20% of the total number of articles produced by Venezuela; by 2018, Peru had outstripped Venezuela’s production by more than double. In 1999, Ecuador was ranked thirteenth in the region regarding production of articles, by 2018, it held the sixth place, tripling Venezuela's article production rate. All this helps demonstrate the decline in academic production rates of Venezuelan universities, the main producers of scientific articles in the country, which may further decrease due to the continuous leaving of university personnel.

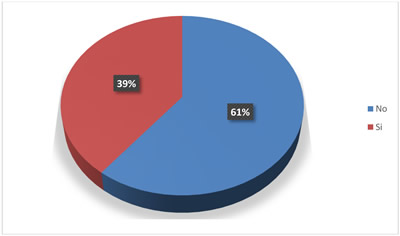

It is interesting to know, considering the profile that we have characterized based on the sample collected, whether these Venezuelan migrants continue exercising or working in the university context in the host countries. According to the data obtained, no; most of these migrants did not continue working in university teaching; many had to redefine themselves professionally, undertaking a new life project, working in other fields, many of them radically different from university functions.

Source: authors’ own creation.

Chart 7. Currently working as a university professor in the host country.

Out of the 373 people in the sample, 147 stated that they are working in universities in their host countries and many of them affirmed that they continue developing their lines of research by participating in teams to train new talents in these countries. Most of them, 226, indicated that they are not working in university academic activities.

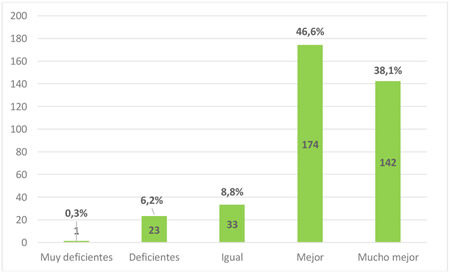

Regardless of whether they are working or not as university professors, most of them think that their life conditions are better or much better compared to their conditions by the time they left Venezuela.

Source: authors’ own creation.

Chart 8. Current life situation compared to the one they had by the time they left Venezuela.

The only person who stated that their current living conditions are far more deficient than the ones they had in Venezuela said: In Venezuela I had my own apartment, without a mortgage, 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, and a parking lot with my own car. Here I live in a rented room and I don’t have a car. Without a doubt, it is a radical change regarding their housing situation. These are the changes that a migrant must endure. These types of situations are sometimes linked to the amount of time a migrant has been in the host country. Attaining good living conditions in a new country usually takes time, even more if the migration process was not planned with sufficient time and resources.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The migration phenomenon in Venezuela is very recent. A country that welcomed migrants from different continents for decades has now become a migrant-sending country over the past years, thus making the study of migration from various perspectives necessary. This article studies the migration process of Venezuelan university professors, with the objective of defining and characterizing them within the migratory dynamics that affect the Venezuelan population. Due to the data collection techniques, this is only a first approach to the characteristics of these migrants and their possible impact on the institutional and academic dynamics of Venezuelan universities.

Conceptually, the group under analysis is characterized as forced skilled migration, which had the necessity of leaving their home country and modifying their profession; initially their academic career. Unlike the literature review conducted, this group exhibits a migratory dynamic of a professional and intellectual sector not necessarily driven by the human talent global market, but by the deterioration of the living and working conditions of their country of origin; a fact that makes it not an individual phenomenon, but a massive one, which has been acknowledged by international organizations such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. In addition to the massive outflow of citizens, this organization points out that the situation concerning human rights in Venezuela is troubling, and specifies, among other problems, the following: (a) the authorities not acknowledging the crisis; (b) complaints of murders during activities performed by special action forces; (c) healthcare system deterioration; (d) restrictions on freedom of expression and the press; (e) increased school exclusion due to the crisis; (f) collapse of public services; (g) criminalization of protests (UN, 2019). Venezuela’s institutional and humanitarian crisis is real.

The sample of migrant university professors from Venezuela is mainly comprised of Venezuelans, who are married, or with a sentimental partner, young or at an economically active age to continue developing their academic careers, who resided in Greater Caracas (Caracas and adjacent cities). Regarding gender, they are exactly 50% men and 50% women, and less than a third has a second nationality.

These migrant university professors are currently living, mainly, with their spouses and children and have left behind a part of their nuclear family (mother, father, grandparents) in Venezuela. The migratory process has apparently reshaped the family relationships of this migrant group, marked by the people with whom they are currently living and those who are far away.

Most of the group under study left Venezuela in the 2015-2018 period, and has moved to Spain, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, the United States and Argentina, with South America being the region with the highest influx of Venezuelans. They estimate that they will stay in their host country for at least three years, although their possibilities of returning depend on the political and economic changes that may occur in Venezuela. The decision to return, as well as the decision to migrate, is not just a personal decision, it tends to involve other family members and has economic implications associated to it. When the appropriate conditions in the country of origin prevail, families return with the largest financial reserves possible, so that their return does not turn into a failure but a migratory success (Stark & Bloom, 1985).

The main reasons for migrating were political, economic, insecurity, and work; these reasons pivot around the socio-political circumstances under which the country is, that emerged due to the imposition of a hegemonic political project that restricted civil freedoms and destroyed the liberal democratic institutional system to impose a new one-party political-military class. All this has led to a complex humanitarian crisis that all Venezuelans in general have to endure, and that has caused a significant number of university professors to seek basic standard conditions to live.

As for their academic characteristics, the participants of this group were members of the teaching and research staff of public universities mainly located in Caracas, and especially of the Central University of Venezuela, who enjoyed job stability (tenured), were full-time professors, or were under an exclusive contract. Although the participants in the group were distributed among the different academic levels, the ranks of Instructor (starting the academic career) and Full Professor (finishing it) stood out. Regardless of their ranks, almost all the professors in the sample have postgraduate studies, and almost half hold a Ph.D. degree, with active lines of research in their universities by the time they left the country. Even though they are not part of any university teaching staff in their host country, they consider that they have better living conditions now compared to the ones they had in Venezuela.

The results indicate that Venezuelan universities seem to be suffering a substantive loss of its human talent. Their expertise, their years of experience, and time of service left to be eligible for retirement, make this migrant group a significant loss for Venezuelan universities, regarding teaching and research. It also seems that a portion of the next generation of professor that was expected to assume greater responsibilities in the next 10 or 15 years has left the country. Certainly, all of them will be replaced with talented young people, keen to work, but who would be just taking their first steps in their academic careers; hence they must complete their training cycle. They have to undertake postgraduate studies without economic incentives, in a country with hyperinflation and with salaries that are not sufficient to even cover the market basket. And a portion of the professors who were expected to train the next generation of Venezuelan universities has also migrated. This is the group that was in the rank of Full Professor, with Ph.D. and Master’s degrees, meant to aid in the training process of talented youths who would start their academic careers at universities and undertake postgraduate studies.

Although there are still resilient professors in Venezuela, who defend universities from the attacks of the government for the sake of training specialized human resources, there is no doubt that the outflow of the professionals that comprise the sample under analysis leaves Venezuelan universities in very poor conditions to face the challenges that lie ahead, even if there is a short-term change in the state’s policy regarding universities.

Therefore, it seems that the generation of university professors who will bear the responsibility of training future university professionals will be those youths who opt to stay in the country and exercise teaching, with the additional commitment of studying in the postgraduate programs that remain active in Venezuela. This would be a similar situation to the one experienced by Venezuelan universities in the early 1960s.

The migration phenomenon is complex and manifold, and cannot be viewed as groups of people who change their place of residence. The sample studied suggests that it is a complex process that involves the family, State policies, and economic and cultural factors that affects both the country of origin and the host country. In this work, a first approach has been made to quantify and describe the migration process of university professors. But it is necessary to delve into the reasons for their migration, and also, how they integrate into the host country, in general, and into the work market, placing emphasis on their reintegration process into the university world.

6. REFERENCES

AUTHORS:

Audy Salcedo

He holds a Degree in Education with specialization in Mathematics by the Central University of Venezuela. He holds a Master’s Degree in Teaching of Mathematics and a Ph.D. in Education. He currently works as a professor of Statistics Applied to Education in undergraduate and graduate degrees at the same university. He is also a professor in the Doctorate in Education at the Andres Bello University of Venezuela. In the Central University of Venezuela, he has held various university management posts: Executive Coordinator of the Inter-Faculty Cooperation Program; Head of the Center for Educational Research; Head of the Department of Statistics and Informatics Applied to Education; Department Chair of Quantitative Methods. He has various national and international publications. He is an Associate Editor of Areté, Revista Digital del Doctorado en Educación de la Universidad Central de Venezuela.

audy.salcedo@ucv.ve.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9783-8509

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=dFInkAkAAAAJ&hl=es

Ramón Alexander Uzcátegui Pacheco

He holds a Ph.D. in Humanities (UCV, 2010), and a Degree in Education (UCV, 2005); a Post-doctoral Degree in Philosophy and Education Sciences (UCV, 2016); a Master’s Degree in Educational Research and Innovation (UNED-2019). He did a Post-doctoral Internship at the Playa Ancha University (Chile, 2018); and a Research Stay at CEINCE (Soria-Spain, 2019). Professor at the Playa Ancha University, Chile (2018), at Santo Tomás University (2018), and at Andres Bello University of Chile (2019). He is member of the Study Group “Enseñanza de la Historia, Ciudadanía y Educación” (UC, UNAB, UPLA - Chile); member of the Line of Research Memoria Educativa Venezolana (UCV-Venezuela); Member of the Latin America, Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean International Network (ALEC — Université de Limoges-France). He is Editor of the Revista de Pedagogía (UCV, 2016-2018); Accredited Researcher: PEII-Venezuela, 2nd Level (2010-2015). Researcher registered in CONCYTEC-Perú (2018); Researcher with publications in the fields of Education, Pedagogy, History of Education, and School Texts.

razktgui@gmail.com

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5669-6663

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=g-0-Y2wAAAAJ&hl=es