doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1310

INVESTIGACIÓN/RESEARCH

THE IMPACT OF ENJOYMENT AND ANXIETY ON ENGLISH-LANGUAGE LEARNERS’ WILLINGNESS TO COMMUNICATE

EL IMPACTO DEL DISFRUTE Y LA ANSIEDAD EN LA VOLUNTAD DE COMUNICARSE DE LOS ESTUDIANTES DEL IDIOMA INGLÉS

O IMPACTO DA DIVERSÃO E DA ANSIEDADE NA VONTADE DOS ALUNOS DE INGLÊS PARA SE COMUNICAR

Elias Bensalem1

1Northern Border University. Saudi Arabia

ABSTRACT

Willingness to communicate (WTC) plays a pivotal role in second language learning (Clément et al., 2003; Kang, 2005; Yashima et al., 2004) because a high level of WTC may help learners achieve language proficiency (MacIntyre et al., 2003; Yashima et al., 2004). Therefore, MacIntyre et al. (1998, p. 547) asserted that the major goal of language learning should be WTC. Willingness to communicate in a foreign language is linked to a range of negative emotions (i.e., anxiety and boredom) and positive emotions (i.e., enjoyment and pride). Inspired by the shift from negative psychology to positive psychology in the field of second language learning, the present study aimed to investigate whether language enjoyment and anxiety are potential predictors of WTC. A group of 349 English as a foreign language (EFL) undergraduate students (female = 226, male = 123) enrolled at public Saudi Arabian universities were surveyed. Quantitative data were collected during one month. Descriptive analyses revealed above-average levels of WTC of the participants. Multiple regression analyses revealed that foreign language enjoyment (FLE) was a predictor of WTC but foreign language classroom anxiety (FLA) did not correlate significantly with students’ WTC. These results suggest higher levels of enjoyment may have neutralized the effects of anxiety on WTC, indicating the role of positive emotions. Implications for foreign language teachers are discussed.

KEYWORDS: willingness to communicate, foreign language classroom anxiety, foreign language enjoyment, English language learners

RESUMO

A vontade de se comunicar (WTC) desempenha um papel fundamental na aprendizagem de uma segunda língua (Clément et al., 2003; Kang, 2005; Yashima et al., 2004) porque um alto nível de WTC pode ajudar os alunos a alcançar a proficiência linguística (MacIntyre et al. , 2003; Yashima et al., 2004). Portanto, MacIntyre et al. (1998, p. 547) afirmaram que o principal objetivo da aprendizagem de línguas deveria ser o WTC. A vontade de se comunicar(ou não) em uma língua estrangeira está ligada a uma gama de emoções negativas (ansiedade e tédio) e emoções positivas (prazer e orgulho). Inspirado pela mudança da psicologia negativa para a psicologia positiva no campo da aprendizagem de uma segunda língua, o presente estudo teve como objetivo investigar se o prazer com o uso da linguagem e a ansiedade são potenciais preditores de WTC. Um grupo de 349 alunos de graduação de inglês como língua estrangeira (EFL) (mulheres = 226, homens = 123) matriculados em universidades públicas da Arábia Saudita foram pesquisados. Os dados quantitativos foram coletados durante um mês. As análises descritivas revelaram níveis acima da média de WTC dos participantes. Análises de regressão múltipla revelaram que o prazer em falar em língua estrangeira (FLE) foi um preditor de WTC, mas a ansiedade em sala de aula de língua estrangeira (FLA) não se correlacionou significativamente com o WTC dos alunos. Esses resultados sugerem que níveis mais elevados de prazer podem ter neutralizado os efeitos da ansiedade no WTC, indicando o papel das emoções positivas. Implicações para professores de línguas estrangeiras são discutidas.

PALAVRAS CHAVES: vontade de comunicar, ansiedade em sala de aula de língua estrangeira, prazer em língua estrangeira, Alunos de língua inglesa

Received: 22/02/2021

Accepted: 05/08/2021

Published: 03/01/2022

Correspondence

Elias Bensalem. Northern Border University. Saudi Arabia bensalemelias@gmail.com

How to cite this article

Bensalem, E. (2022). The impact of enjoyment and anxiety on English-language learners’ willingness to communicate. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 155, 91-111. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1310

Declaration of interest statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. INTRODUCTION

One of the main goals of foreign language (FL) teaching is to prepare students to speak in the target language (MacIntyre et al., 1998). Therefore, teachers need to help learners gain communicative competence (Khajavy et al., 2016). However, achieving competence does not always result in willingness to communicate (WTC). One definition of WTC is that it refers to “a readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons” (MacIntyre et al., 1998, p. 547). Research suggests that several emotions such as anxiety influence WTC (Elahi et al., 2019). Despite investigators having documented the link between foreign language anxiety (FLA) and WTC, the role of positive emotions in fostering or limiting WTC, especially among Arab EFL learners, has not received sufficient attention from scholars. Dörnyei and Ryan (2015) recently called for more studies that include positive emotions in second language acquisition (SLA). They argued that “feelings and emotions play a huge part in all our lives, yet they have been shunned to a large extent by both the psychology and the SLA literature” (p. 9). A similar call was made by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014, 2016), who asserted that positive emotions, especially foreign language enjoyment (FLE), should be investigated. In the same vein, MacIntyre and Mercer (2014) maintained that "models of the learning and communication process are incomplete without explicit consideration of positive emotions, individual strengths, and the various institutions and contexts of learning" (p. 165). More recently, Wang et al. (2021) argued that the effects of various emotions as well as the relations between these emotions and WTC should be examined in diverse language contexts. Therefore, the present study is an answer to this call to investigate positive emotion (enjoyment) combined with negative emotion (anxiety) and their relationship with WTC.

1.1. Literature review

The framework of this review of the research literature is a discussion of the constructs of FLA and FLA, and how they might influence students’ WTC.

1.1.1. Foreign Language Enjoyment and Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety

For decades there was an exclusive focus on negative emotions in second language acquisition (SLA), namely anxiety since the 80’s, especially after the seminal work of Horwitz et al. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety is defined as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings and behaviors related to classroom learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process” (Horwitz et al., 1986, p. 128). Eysenck et al. (2007) argue that anxiety causes individuals to be subject to distractors which undermine their cognitive processing efficiency. Distractors such as worry over possible failure and concern over the opinions of peers (Dewaele 2013) may results in lowering WTC. (Zhou et al., 2020). With the emergence of positive psychology in SLA, the profession has witnessed a major shift from a sole focus on negative emotions to considering the role of positive emotions namely, foreign language enjoyment (FLE) which refers to the state of experiencing enjoyment in learning a foreign language (Lee, 2020).

Positive emotions contribute to learners' well-being (MacIntyre et al., 2019). They are believed to play a role in increasing students' motivation, the enhancing language learning process (MacIntyre & Gregersen, 2012), and developing resilience, which is necessary to alleviate the crippling effects of negative emotions (Dewaele et al., 2018; MacIntyre et al., 2019).

The one type of positive emotion that has received most attention since the onset of the positive psychology movement is enjoyment, especially since publication of Dewaele and MacIntyre's (2014) study. Several studies reported that enjoyment was one of the most frequently experienced positive emotions (Dewaele & Li, 2018; Elahi Shirvan & Taherian, 2018; Pavelescu & Petric, 2018). Boudreau et al. (2018) characterize foreign language enjoyment as a "complex and stable emotion" that is completely separate from the "more superficial experience of pleasure" (p.153). FLE and FLA have been conceptualized as being two different but related dimensions (Dewaele & Dewaele, 2017; Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014, 2016). They should not be perceived in a see-saw relationship because an increase in the level of one construct does not necessarily mean a decrease in the other (Boudreau et al., 2018; Dewaele & Li, 2018).

The association between FLE and FLA has been the subject of a growing number of studies that were conducted in both local and international educational contexts (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014, 2016), involving different second language (L2) learners. In a major study involving 1,740 FL learners from around the world, Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) reported a significant negative correlation between FLE and FLA. A close examination of the participants' scores on FLE and FLA measures revealed that the two dimensions are not opposite constructs. The researchers argued that a learner may not experience enjoyment but still have no level of FLA. In other words, it is not uncommon for a learner to experience both low levels of enjoyment and low levels of anxiety simultaneously (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014). Furthermore, the researchers reported that learners who exhibited significantly higher FLE and lower FLA had a higher level of multilingualism and a more advanced level of proficiency. These results were corroborated by Dewaele et al. (2018). Their study with a group of 189 secondary school students who were mostly taking French, German, or Spanish courses in the UK reported a weak negative relationship between FLE and FLA. Students had significantly higher levels of FLE than FLA.

The dynamic relationship between FLE and FLA was the subject of a study by Boudreau et al. (2018). The participants were a small group of 10 college-age English-speaking students learning French as an L2. Participants were required to complete oral tasks while being video recorded. Idiodynamic software was used to rate students' anxiety and enjoyment. The researchers examined the correlation between FLE and FLA for each participant and the fluctuating relationships between FLE and FLA. There was a complex correlation between FLE and FLA. In some cases, FLE and FLA moved closer to each other, while in others they were further apart. Both acted separately.

A series of empirical studies on potential differences between FLE and FLA was conducted in context of Asian schools. For example, Jiang and Dewaele (2019) compared FLE and FLA of EFL Chinese students to their peers in other countries. Chinese learners reported significantly higher levels of enjoyment than anxiety in their English classes. This finding is in line with outcomes of previous research (Dewaele et al., 2017; Dewaele & Dewaele, 2017; Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014; Khajavy et al., 2018). The means of FLE and FLA were higher than the mean in the Dewaele and MacIntyre’s (2014) sample. The researchers suggested that the high levels of anxiety among Chinese students is attributable to the educational system in China, which does not emphasize enough practice of the English language (see Shi, 2008).

Investigating the constructs of FLE and FLA in the context of Saudi schools has begun to draw the interest of scholars. Dewaele and Alfawzan (2018) examined the effect of FLE and FLA on English language performance among a group of 152 participants that included undergraduate students and nonstudent users of English. Participants’ levels of FLE were correlated with English proficiency scores, but FLA was inversely related to English proficiency scores. The researchers concluded that there were interactions between participants' experience of FLE and FLA in their English classes.

1.1.2. Willingness to communicate in a foreign language

The construct of WTC was initially considered a personality-based trait in first language (L1) when introduced by McCroskey and Richmond (1991). Personality traits are deemed to be consistent across different situations. Similarly, Baker and MacIntyre (2000) argued that WTC is a trait-like predisposition. In other words, people’s tendencies to communicate are the same no matter how different the communication contexts. In the 1990s, researchers started to examine WTC in an L2 context (see, e.g., MacIntyre, 1994). The construct of WTC refers to “a readiness to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using an L2” (MacIntyre et al., 1998, p. 547). Unlike L1 WTC, WTC in a foreign language is considered more variable because L2 learners are presented with different communication opportunities. Research has provided evidence that WTC differs from one FL student to another. It evolves over time and across different linguistic situations (MacIntyre et al., 1998). Students are subject to internal and external factors that they may not be able to control. The language setting where students live may affect students’ motivation and a desire to communicate in the target language (D’Orazzi, 2020).

Numerous studies have identified a number of affective variables that seem to influence WTC in a foreign language, namely, L2 motivation (Hashimoto, 2002; Lee & Drajati, 2019; Wu & Lin, 2014), self-confidence (Lee & Drajati, 2019; MacIntyre et al., 1998), perceived communicative competence (Baker & MacIntyre, 2003; Shirvan et al., 2019; Yu, 2008), anxiety (Ghonsooly et al., 2012, 2013; Hashimoto, 2002; Knell & Chi, 2012; Liu, 2018; MacIntyre et al., 2002; MacIntyre & Doucette, 2010; Riasati, 2018; Wu & Lin, 2014), and grit (Lee, 2020).

MacIntyre and Doucette (2010) examined WTC among high schoolers learning French as a foreign language in Canada. The authors reported that WTC inside class was predicted by perceived competence and FLA. Students who perceived themselves competent in the target languages tended to have higher levels of WTC. In addition, many students were not able to complete tasks and refrained from participation as a result of anxiety. The impact of FLA on WTC was also experienced by British secondary school students’ WTC in French, German, and Spanish (Dewaele & Dewaele, 2018).

A number of studies examined the potential impact of the construct of FLE on WTC among second language learners. Khajavy et al. (2017) demonstrated that Iranian EFL learners’ WTC was determined by FLA as well as by FLE. Although enjoyment helped increase students’ level of WTC, anxiety decreased students’ WTC. In a more recent study, FLE and FLA were related to the WTC of two Romanian teenage EFL students (Dewaele & Pavelescu, 2019). Although researchers have started to examine the role of negative and positive emotions on WTC, the number of studies is still limited. It is unclear whether FLE along with FLA influence EFL learners’ L2 WTC in different socioeducational contexts, especially in the Arab peninsula.

The present study examines the role of FLE and FLA in Saudi EFL learners’ WTC at the college level. It is among the few studies that involve EFL learners in the underexplored Gulf region. The results of this study will advance our understanding of the relationship between affective variables and L2 WTC in similar contexts along with pedagogical implications for ELT. The following research questions are addressed:

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

A total of 349 EFL undergraduate students (female = 226, 64.8%; male = 123, 35.2%) aged between 18 and 24 years from two universities in Saudi Arabia took part in the survey. All students were enrolled in languages and translation departments. Among the students, 21.2% (n = 74) were freshmen, 17.8% (n = 62) sophomores, 21.2% (n = 74) juniors, and 39.8% (n = 139) seniors. All students were required to take English classes in a preparatory English program prior to enrollment at the department. The preparatory program is an intensive five-course (half-semester) training that aims to develop the English proficiency required at a university. By the end of the program, students are expected to achieve at least an intermediate level of proficiency in English. None of the participants reported study-abroad experience.

2.2. Instrument

The questionnaire consisted of four sections: L2 WTC, FLA, FLE, and demographic questions. Twelve items of WTC (e.g., ‘Volunteer an answer in English when the teacher asks a question in class’), which were adapted from Cao and Philp (2006) and Weaver (2005) were used to gauge the participants’ levels of WTC in the classroom using English. Answers to these question items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘definitely not willing’ to ‘definitely willing’. Coefficient alpha for these items was .91). To assess students' anxiety, eight items (e.g., ‘Even if I am well prepared for my English class, I feel anxious about it’), extracted from the FLAS (Horwitz et al., 1986) and adapted from Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014), were used in this study with a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Six items were negatively worded to indicate anxiety. The two remaining items, which were positively worded, were reverse coded. One item was removed from scale to ensure an acceptable level of internal reliability with coefficient alpha = .71. Ten items (e.g., ‘I enjoy my English class’) from Dewaele and Dewaele (2017) that were extracted from the original 21-item FLE questionnaire (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014) were used to measure participants’ FLE. The items, which were all positively phrased, were based on 5-point Likert options (1= strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). Coefficient alpha for these FLE items was .76. The fourth section was designed to elicit participants’ gender, age, and year of study. The participants were given the choice between answering the survey in English or in Arabic. They felt more comfortable answering items written in their native language. The Arabic version of the survey was validated. One professor of translation translated the survey into Arabic. Then a second professor back translated that version to English. Both professors are native speakers of Arabic. The researcher checked the back translation against the original English to ensure the meaning of each survey item remained intact.

2.3. Data collection

The survey was administered via Google Forms and shared via social media networks (Twitter and WhatsApp groups) to generate a snowball sample. Respondents gave informed consent before filling out the survey and were briefed on the consent page about the purpose of the study and that the responses would be anonymous and used for research purposes only. The survey was kept online from March to April 2020 and received 373 responses. Only 349 responses were valid since the rest were incomplete.

2.4. Data analysis

Means and standard deviations were computed to summarize participants' responses. Spearman rho was used to analyze relationships of WTC with FLE and FLA. Multiple regression analysis was used to determine whether FLE and FLA are predictors of WTC.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive data

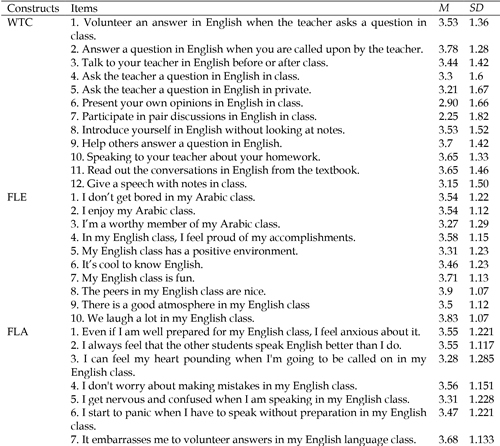

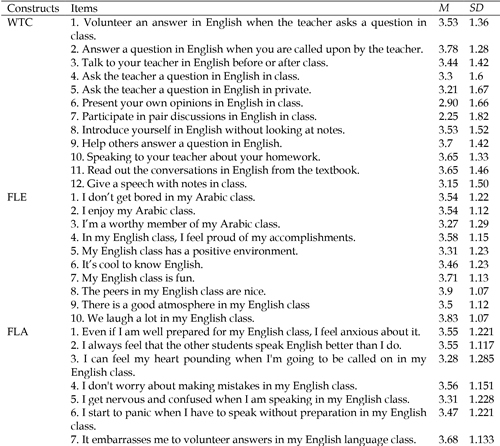

Descriptive statistics on WTC, FLE, and FLA are presented in Table 1. Overall, the students had above-average levels of WTC (M = 3.40, SD = 1.03) in English on a 5-point scale (68%). The participants tended to have higher WTC when called upon by the teacher to answer a question, speak to their teacher about their homework, or read aloud the conversations in English from the textbook. Enjoyment (M = 3.92, SD = 0.65) (78%) was scored highest, followed by FLA (M = 3.48, SD = 0.73) (70%). This suggests that participants had generally higher levels of enjoyment than anxiety.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations on Scale Items

3.2. Correlation analysis

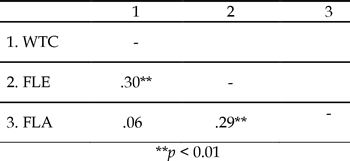

In order to examine data normality of WTC, FLE, and FLA, Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were performed. These tests revealed that the distribution of each variable was not normal (WTC, D(349) = 1.24, p < .001; FLE, D(349) = 0.08, p < .001; FLA, D(349) = 0.1, p < .001). Therefore, Spearman’s rho was used to assess the relationships of WTC with FLE and FLA. WTC levels were significantly correlated with FLE, rs(349) = .30, p < .001. In other words, students with higher levels of WTC tended to experience higher levels of enjoyment. According to Cohen’s (1988) conventions to interpret effect size, correlation coefficient of .30 is considered a moderate correlation, this indicates a medium effect size. WTC and FLA were not correlated with each other, rs(349) = .06, p = .811.

Table 2. Correlations among variables

3.3. Predictors of WTC

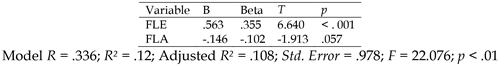

Multiple regression analysis was conducted to investigate whether FLE and FLA were predictors of WTC. The results are presented in Table 3. There was a significant relationship between the two independent variables (FLE and FLA) and WTC (p = .001; R² = .12; R =. 336). About 34% of the variance in WTC was accounted for by the independent variables. Enjoyment was a predictor of WTC with t value of 6.640, while FLA was not a predictor of WTC with t value of -1.913.

Table 3. Regression Model for Predicting WTC

4. DISCUSSION

In this section, the main findings of the current study are discussed. The first research question examined levels of WTC, FLE, and FLA among EFL Saudi students. In the current study, participants reported above-average levels of WTC in English, which are below the levels reported by EFL learners from other educational settings such as Chinese students who reported high levels of WTC (80.33%) (Zhou et al., 2020). These results are not surprising because Saudi students are often reported as unwilling to engage in conversations due to a perceived lack of communicative competence and self-confidence (Turjoman, 2016). EFL teachers’ lack of qualifications (Al-Hazmi, 2003) could have contributed to the creation of a classroom environment where students are not given enough opportunities to communicate in the target language. Some teachers are not trained to implement teaching methods that are learner centered. Results from the present study show also that Saudi EFL students experienced fairly high levels of enjoyment, comparable to the values reported in previous studies involving Saudi students, ranging from 68% (M = 3.4) (Dewaele & Alfawazan, 2018) to 72% (M = 3.61) (Bensalem, 2021). Participants’ anxiety was lower than levels reported in a recent study involving EFL Saudi students 74% (M = 3.70) (Bensalem, 2021) but higher than levels reported by recent studies with a range between 48% (M = 2.4) (Dewaele et al., 2017) and 62% (M = 3.1) (Jiang & Dewaele, 2019). This outcome corroborates the findings reported in previous studies, which state that Saudi EFL learners tend to experience higher levels of anxiety when compared with students in other countries (Alrabai, 2015). Students’ experience of high anxiety levels could be attributed to the educational context in Saudi where students are not sufficiently exposed to English because instructors tend to use Arabic extensively in the classroom (Alrabai, 2016).

The second research question involved is the possibility of a significant difference between levels of FLA and FLE experienced by the EFL Saudi students in this study. Enjoyment was higher than anxiety, thus confirming findings reported by Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) and Khajavy et al. (2017). Despite the different educational and cultural context, with a mean of 3.92, the Saudi students in this study had a similar level of enjoyment to their peers in Iran (Khajavy et al., 2017), China (Jiang & Dewaele, 2019), and around the world (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014), where the means were 3.90, 3.90, and 3.82, respectively. However, with a mean of 3.48, the Saudi students reported higher levels of anxiety than did Chinese (M = 3.1), Iranian (M = 2.53), and other students from around the world (M = 2.75).

Results relating to the third research question lend further support to the argument that FLE is one of the prominent predictors of WTC. The current study provides evidence that students who experience enjoyment tend to have greater WTC. Similar outcomes were reported in research involving EFL learners from Spain (Dewaele, 2019), Iranian secondary school students (Khajavy et al., 2017), and Korean EFL learners from middle school, high school, and university (Lee, 2020).

One important finding generated by the current study is that an association did not exist between negative emotions (FLA) and WTC. Although FLA was significantly correlated with FLE, FLA was not a predictor of WTC. This unexpected outcome is inconsistent with previous research (Dewaele, 2019; Dewaele & Dewaele, 2018; Joe et al., 2017; Khajavy et al., 2018; Lee & Hsieh, 2019; MacIntyre & Doucette, 2010; Oz et al., 2015; Yashima et al., 2016). Dewaele (2019), for example, found that FLA accounted for 30% of variance explained by a regression model. One possible explanation for this outcome is that FLE and FLA are two separate but related dimensions of experience that are not in a strict see-saw relationship (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014). In other words, students’ levels of anxiety, regardless of how low, do not seem to result in an increase in WTC even though the students’ experience of enjoyment is correlated with WTC. In the same vein, Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) and Dewaele et al. (2018) contended that it is possible for learners to experience high levels of FLA and FLE concurrently.

Another possible explanation is that other variables such as the attitudes toward the target language and the instructor (Dewaele & Dewaele, 2017; Dewaele et al., 2018), among other contextual variables, may have neutralized the role of FLA in WTC. According to Fredrickson’s (2003) broad-and-build theory, a positive classroom environment where the teacher is friendly and supportive helps increase students’ interest in exploring opportunities to communicate in the target language. In a study involving college-level Saudi students, Bensalem (2021) reported that learners complained about the instructor’s resorting to intimidation techniques and the inability to create a pleasant learning atmosphere, which resulted in bad learning experiences. In the same vein, Yashima (2002) asserted that WTC is affected not only by psychological reactions to the learning process but also by contextual elements. The learning environment (Dörnyei, 1994) and society in general (Norton, 2013) may influence learners’ motivation to learn an L2. For example, in a recent study in the Australian context, contextual elements such as inconsistent policy and inadequately supported policy initiatives related to language education (Lo Bianco, 2016) may have hampered students’ desire to communicate in the studied L2 (D’Orazzi, 2020). The scarce opportunities to practice oral skills in the target language are reported to affect students’ WTC (D’Orazzi, 2020), which may be the case for participants of the current study. Saudi Arabia is largely monolingual where English is spoken in very limited situations such as hospitals when interacting with non-speakers of Arabic.

The absence of visible effect of FLA on WTC can be interpreted considering MacIntyre and Gregersen’s (2012) argument, which holds that that positive emotions may boost learners’ resilience. Consequently, learners with more perseverance may feel more WTC (Lee, 2020). Dewaele (2019) argued that WTC is linked with several complex emotions that interact with other learner-internal and learner-external variables. These variables have a major impact on the learners’ extent of WTC (Boudreau et al., 2018).

4.1. Implications

The current findings have some pedagogical implications for foreign-language teaching. In order to enhance students’ WTC, teachers should create a positive classroom learning environment where making mistakes is tolerated and WTC is nurtured (Dewaele et al., 2018) in order to improve students’ communication skills (Lee, 2020). The inclusion of classroom activities that boost learner autonomy becomes an important practice because such activities are perceived to be quite enjoyable (Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014). Moreover, teachers should make an effort to introduce more performance-based activities that provide students with opportunities to speak English (Lee, 2020). This can be achieved by selecting topics for conversation of interest to students (Cao, 2014). Interesting topics and varied class activities make students enjoy the contents, which enhances their communication (Wang et al., 2021). Perhaps one of the most important measures that teachers should consider is to provide students with multimodal corrective feedback that includes verbal and nonverbal semiotic resources such as gesture, gaze, and facial expressions (Bayat et al., 2020). Each feedback item provided to students during interactive sessions could be accompanied by video excerpts from the sessions and audio recordings (Vidal & Thouësny, 2015). In a recent study, Bayat et al. (2020) found that multimodal corrective feedback broadened the main dimensions of enjoyment among students by raising their attention to the errors they made and heightened their focus on the correct form. Previous studies have suggested that engaging students’ senses and raising their attention during corrections could cause positive affect such as enjoyment (Boudreau et al., 2018; Dewaele, 2017; Saito et al., 2018). Finally, it is important that teachers should be friendly and supportive of students (Zarrinabadi, 2014). Their continuous encouragement for all students, especially those who are struggling, can lead to an increase in students' WTC.

4.2. Limitations and future research

The present study has limitations. First, WTC, FLE, and FLA were self-reported and may possibly not reflect the actual levels of each construct among participants because self-reports have some degree of generalizability (Dewaele, 2018). Therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Second, data were collected from two universities. Therefore, the outcomes of the current study cannot be generalized to all the Saudi EFL university students. Third, the study did not account for important variables that could have influenced the findings. More specifically, students’ WTC could have been the result of the interaction of a number of learner individual characteristics, such as motivation (Yashima, 2002), L2 confidence (Ghonsooly et al., 2012), learner beliefs (Peng & Woodrow, 2010), and international posture (Yashima, 2002), as well as situational factors including students’ experiences in the classroom (Peng, 2012, Wang et al., 2021). Therefore, future studies should examine the interactive effects of positive and negative emotions as well as a number of individual and situational factors on students’ WTC. Such studies may help depict a picture of how the simultaneous interaction of multiple factors affect students’ learning experiences (Zhou et al., 2020).

Future research could also involve examining the role of grit as an internal variable in Saudi EFL learners’ WTC in different educational conditions involving prestigious and less prestigious universities. Finally, the data of the current study were collected prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Future research can examine whether there is a significant difference between the impact of negative and positive emotions students’ WTC in-person and virtual classes.

5. CONCLUSION

The present study has involved an investigation of positive emotion (enjoyment) combined with negative emotion (anxiety) and their relationship with WTC among university-level students in Saudi Arabia, which is an underexplored context. The findings showed that participants had higher levels of enjoyment than anxiety. In addition, the study confirmed the active role of enjoyment as an important positive emotion in WTC construct. The impact of anxiety on WTC was not salient, however, because it did not predict students’ WTC. High levels of enjoyment may have neutralized the impact of anxiety on WTC together with the potential effects of learner individual and situational factors, which have not been accounted for in this study. Therefore, future research could be used to examine the potential role of other constructs such as grit, combined with other negative emotions such as boredom, on learners’ WTC in various contexts.

REFERENCES