doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1392

RESEARCH

APPLICATION OF SENSORY MARKETING TECHNIQUES IN FASHION SHOPS: THE CASE OF ZARA AND STRADIVARIUS

APLICACIÓN DE LAS TÉCNICAS DE MARKETING SENSORIAL EN LOS ESTABLECIMIENTOS DE MODA: EL CASO DE ZARA Y STRADIVARIUS

APLICAÇÃO DAS TÉCNICAS DE MARKETING SENSORIAL NAS LOJAS DE MODA: O CASO ZARA E STRADIVARIUS.

Pedro Pablo Marín Dueñas1

Diego Gómez Carmona1

1University of Cádiz. Spain

1Pedro Pablo Marín Dueñas: doctor. University of Cádiz. Assistant Professor at Marketing and Communication's Department. Coordinator of Marketing and Market Research Degree.

ABSTRACT

The growing importance of online shopping portals compared to physical retail makes it necessary to develop strategies at the point of sale to continue to go there to buy. In this sense, one of the big differences (if not the strongest point) between the physical shop and the online store is the physical experience of being able to touch and feel the product. The shop should not only be understood as a point of sale but should also be configured as a space in which to live experiences. Moreover, it is integrated within the trade marketing strategy, where the senses' marketing takes on particular relevance. Based on this premise, this research focuses on the study of sensory marketing used by the fashion shops of the Inditex group Stradivarius and ZARA and, more specifically, on how they apply these techniques in their shops, from the point of view of smell, hearing, sight and touch. In order to carry out the analyses, the content analysis methodology will be applied. The results show that these establishments actively apply sensory marketing techniques, being present in all the shops to improve the shopping experience for consumers.

KEYWORDS: Sensory marketing. Neuromarketing, Retail marketing, Trade marketing, Merchandising, Fashion, Point of sale, Senses, Inditex

RESUMEN

La creciente importancia de los portales de compra online frente al retail físico, hace necesario el desarrollo de estrategias en el punto de venta para que los consumidores sigan acudiendo a las mismas a comprar. Y, en este sentido, una de las grandes diferencias (por no decir el punto fuerte) entre la tienda física y la online es la experiencia física de poder tocar y sentir el producto. La tienda no debe ser entendida solo como un punto de venta, sino que se debe configurar como un espacio donde vivir experiencias. Y es aquí, integrada dentro de la estrategia de trade marketing, donde cobra especial relevancia el marketing de los sentidos. Partiendo de esta premisa, la presente investigación se centra en el estudio del marketing sensorial utilizado por las tiendas de moda del grupo Inditex Stradivarius y ZARA y, más concretamente, en como aplican estas técnicas en sus tiendas, desde el punto de vista del olfato, el oído, la vista y el tacto. Para ello se aplicará la metodología del análisis de contenido. De los resultados se desprende que estos establecimientos aplican de manera activa las técnicas de marketing sensorial, estando presentes en todas las tiendas, al objeto de mejorar la experiencia de compra de los consumidores.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Marketing sensorial, Neuromarketing, Retail Marketing, Trade marketing, Merchandising, Moda, Punto de venta, Sentidos, Inditex

Correspondence

Pedro Pablo Marín Dueñas. University of Cádiz. Spain. Spain pablo.marin@uca.es

Diego Gómez Carmona. University of Cádiz. Spain. Spain diego.gomezcarmona@uca.es

Received: 01/07/2021

Accepted: 16/09/2021

Published: 03/01/2022

How to cite the article

Marín Dueñas, P. P. and Gómez Carmona, D. (2022). Application of sensory marketing techniques in fashion shops: the case of Zara and Stradivarius. Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación, 155, 17-32. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1392

Translation by Paula González (Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Venezuela)

1. INTRODUCTION

Fashion retail is currently facing a series of problems derived, mainly, from the development of new technologies. On the one hand, the boom in online sales that allows the buyer to access products through the screens of their computers, mobiles, or tablets, and, on the other, the unlimited access to information that the Internet allows and that turns consumers into much more informed and demanding users who no longer limit themselves to buying products but seek to enjoy the shopping experience. Furthermore, globalization brings with it the oversaturation of markets in which products that are difficult to differentiate and highly competitive can be found. Faced with this difficult situation, the physical store has to give an effective response for the consumer to visit the point of sale and buy from it. In short, it is about the retail sector evolving by adapting its merchandising management to the new needs of consumers, creating shopping experiences that connect with the customer on an emotional level.

And in this evolution of the management of the point of sale, the so-called sensory marketing has emerged as a tool linked to experiential marketing that seeks to create shopping experiences through which a consumer can live a unique moment during the time they are in the establishment generating in them emotional reactions that improve brand-consumer relationships. In fact, for authors such as Segura and Sabaté (2008), the final choice of the consumer will be determined by the emotions that the purchase process arouses in them. To awaken these emotions, sensory marketing seeks differentiation through sight, hearing, taste, touch, and smell (De Garcillán López, 2015)

In fact, the increasing development of these actions in commercial establishments is influenced by research that has shown that humans remember more of the sensory impacts linked to emotions, making them more durable. And this is something that online commerce cannot offer, so fashion stores should take advantage of this benefit by offering to experience that sensation in their stores, reinforcing the emotions of the buyers.

In short, consumers are not only influenced in their purchasing decisions by the price or quality of the product but also variables such as the setting of the store, the smell, the perception of the colors associated with the establishment, or simply having a good impression regarding the cleanliness and order of the store become decisively important in the act of purchase, which is no longer considered as something solely rational (de Garcillán López, 2015).

All this has led to an increase in academic activity in this area of knowledge in recent times (Schmitt, 2007; Hultén, 2011; Gómez and García, 2014) and this work aims to continue deepening this line of research based on the analysis of the management of these techniques that involve the senses made by fashion establishments.

1.1. Defining marketing of the senses

De Garcillán López (2015) establishes a differentiation between traditional marketing and marketing of the senses based on the rationality of the former against the importance that experiences and emotions have for consumers, who behave more guided by their impulses than by their reasons. Faced with the idea that consumer behavior is based on the satisfaction of needs from an adequate offer, sensory marketing places emotion as the axis around which it revolves and focuses the purchase process on the experimentation of sensations linked to this process.

Thus, the marketing of the senses allows influencing the perception, judgments, and behaviors of consumers creating a pleasant environment that increases the time of purchase at the point of sale (Ber?ík et al., 2020; Jiménez, Bellido, and López, 2019; Bilek, Vietoris, and Ilko, 2016; Tauferova et al., 2015). This technique is an advantage for retailers compared to online commerce. Consumers can experience through their senses the experience in physical stores, especially in those products that require touching, feeling, and testing before the purchase decision (Kim et al., 2020). Specifically, those retailers that are dedicated to fashion retail have another advantage since, unlike other goods that do not require physical evaluation before their acquisition, clothes must be seen, touched, and generate a previous experience before deciding their purchase (Kim et al., 2020). This lack of experience in the online environment causes a return rate of over 40% (CNBC, 2016).

Considering this data, fashion establishments should create sensory experiences in which strategies and tactics that involve the five senses are put into practice since their joint implementation has a decisive influence on buying behavior (Hulten, Broweus, and Van Dijk, 2008).

2. OBJECTIVES

The object of study of this research is the fashion retail sector and, more specifically, the application of sensory marketing techniques by the fashion establishments of the Inditex group.

Derived from this object of study, the general objective of the study is to analyze the sensory marketing actions that fashion stores implement at the point of sale to

influence consumer behavior. Specifically, visual marketing, scent marketing, auditory marketing, tactile or haptic marketing will be analyzed in the ZARA and Stradivarius stores.

3. METHODOLOGY

The methodological tool that has been used to respond to the objectives that have been set is observation, defined by Posada (2001) as

The most systematic and logical way for the visual and verifiable record of what is intended to be known; that is, is to capture in the most objective way possible, what happens in the real world either to describe it, analyze it, or explain it from a scientific perspective (p.5)

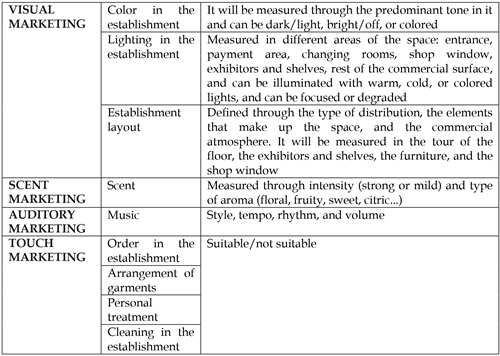

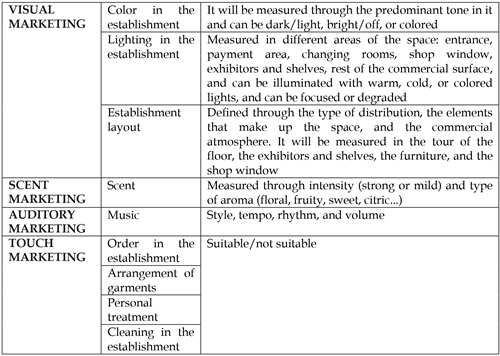

For its application, an analysis sheet has been prepared from the variables defined below (table 1) and which are based on the works of Manzano et al. (2012), Morgan (2016), Palomares (2009), and Díez de Castro et al. (2006). Its application in the points of sale object of study (the ZARA and Stradivarius stores located in the Centro Comercial Área Sur, in Jerez de la Frontera) will allow studying in first person what are the sensory marketing stimuli that are present in them and how the atmosphere of the establishment has been configured to make the purchase process a memorable experience. These two brands of the Inditex group have been selected because they address two types of consumers with well-differentiated characteristics.

Table 1: Analysis variables

Source: own elaboration from Manzano et al. (2012), Morgan (2016), Palomares (2009), and Díez de Castro et al. (2006)

4. RESULTS

From the point of view of visual marketing, the front of ZARA stands out for its large dimensions, its white light lighting, and its modern and attractive architectural style. The shop window is made up of five large windows aimed at attracting different groups of consumers (2 for men, 2 for women, and 1 for children) and decorated with mannequins dressed in the clothing of the current season. The entrance, for its part, stands out for its three large metal doors that invite the passerby to enter as they are wide open. Once inside the store, you can see modern and elegant furniture and decoration consisting of tables, mirrors, and metal and black shelves illuminated with white light, although in the central area of the establishment there are some tables and coat racks that give a feeling of disorder. Likewise, the place is very bright, although the interior lighting can be annoying due to the large number of white light bulbs distributed throughout the establishment. In this sense, the cold light stands out throughout the store except in the payment area, the only point in the store where a warm yellow light can be found.

In the case of Stradivarius, it is also made up of a shop window in which a large window stands out (although, in this case, it is only dedicated to women's clothing,

giving a feeling of simplicity and order and allowing a good view of the garments on display) and a large entrance, divided in two by a column and crowned by the illuminated business logo. Regarding the furniture, it is modern but simple and is composed of wall systems, shelves, wooden tables, circular coat racks, and linear coat racks hanging on the walls, as well as mirrors. The problem is its arrangement that does not follow a clear pattern as in the case of ZARA and causes the movement through the establishment to not be fluid. In terms of lighting, white light also predominates with spotlights that directly and exclusively illuminate both the exhibitors and the shelves. The same goes for the shop window lighting in which the spotlights are focused on the exposed mannequins. On the contrary, the fitting room area is not very well-lit and gives a feeling of overwhelm and disorder.

Regarding scent marketing, in the case of ZARA, the perfume used in the store is one of those that they sell and that is currently being promoted (specifically, the Wonder Rose product). In this case, it was a sweet smell with a certain floral touch. The fragrance was sprayed by the staff themselves from time to time and in the different areas of the establishment. Stradivarius, on the other hand, uses a very characteristic scent and that is developed exclusively for the firm's stores, making it a unique scent (odotype). It is a sweet but very intense smell that is perceived even meters from the entrance. In this case, the fragrance is mechanically vaporized throughout the establishment every half hour.

The same British pop style music plays throughout the entire ZARA establishment and is not differentiated by area. The rhythm of the songs was fast, prompting the consumer to move around the floor in an accelerated manner, although the volume at which it sounded was not very high. In Stradivarius, besides pop, techno and house songs were also played. In all cases, both the tempo and the rhythm of the music were fast and the volume was higher than in ZARA, although it was not annoying. In any case, the music played was tailored to the stores' consumer target.

Finally, in terms of touch marketing in ZARA, the texture and softness of the garments as well as their arrangement encourage you to touch them. Furthermore, the establishment's staff is constantly folding and ordering the clothes so the feeling of cleanliness and organization is very positive, including the changing room area. Likewise, the personal treatment is cordial and the attention to clients both when they advise and when requesting help in looking for a garment or a specific size is very good.

At Stradivarius, the situation is not so optimal. Although, in general, cleanliness and order are good, there is a certain degree of neglect, with messy clothes that have not been folded or placed in their place in a long time, a sensation that is increased in the changing rooms in which it is even noticeable a sense of disinterest in organizing the garments that customers leave and that accumulate in the changing rooms. Regarding personal treatment, in this case, neither the clerks are attentive to the users nor advise them directly, the user being the one who has to go around the

establishment to find a clerk and request their help, which is not the case in ZARA, although the treatment is correct and cordial.

5. DISCUSSION

The results achieved in our research as a result of observation show that the development of visual marketing techniques from ZARA and Stradivarius take advantage of the resources at their disposal, taking care of the front of the shop, the shop windows, the lighting, the signs, and the points of access. That is to say, most aspects related to inbound marketing, aimed mainly at a shopper consumer who is looking for arguments to visit one establishment and not another, are implemented. The advantage of developing these techniques is that it facilitates access to this segment of consumers who are generally guided by price. By applying inbound marketing, it is possible to attract and retain them.

In the case of visual marketing developed inside the store, research shows that at ZARA and Stradivarius there appears to be a certain sense of disorder in the arrangement of the furniture. Previous literature on free arrangement suggests distributing the furniture randomly, allowing the visualization of different sectors of the store and a greater number of products, this distribution allowing a longer staying time at the point of sale and causing a greater volume of impulsive purchases. This seems to indicate that the perceived disorder may be caused on purpose. The brighter lighting in the display section facilitates the visual perception of the garments in the distance while the lighting in the payment area, more subdued, gives the consumer a moment of intimacy, creating a pleasant atmosphere when paying.

Regarding the scent stimuli used by both establishments, there are notable differences, this aspect being less careful in the case of ZARA. The unsystematic use of an aroma can indicate the current search for that fragrance that allows the brand to be identified or that improves the average purchase of consumers. Be that as it may, it seems that in the case of ZARA, the scent marketing strategy is not yet fully implemented and that it focuses more on promoting its perfumes than on achieving an odorous identity. In contrast, Stradivarius clearly uses an odotype linking a particular scent to its brand that gives it the typical advantages of these strategies. That is, it allows it to differentiate itself, improve the memory generated by its products, and the frequency of visits to the point of sale.

Regarding hearing strategies, although the two establishments use music indoors without zoning, they do not take advantage of direct communication (through the public address system, for example) at the point of sale with the consumer. According to the literature, using this type of communication would improve consumers’ trust in the establishment and could encourage promotional purchases.

Lastly, it seems that the texture and softness present in ZARA garments improve the perception of the quality of the establishment. Stradivarius, on the other hand, should improve the placement of the garments by helping consumers with their haptic perception, which is not possible to capture due to the lack of organization. Considering that part of the quality of clothing is perceived by touch, making it difficult for the consumer to touch the products implies a lack of important information when making judgments about the quality of clothing.

6. CONCLUSIONS

It is a fact that the development of sensory marketing has managed to capture the attention of marketing researchers by generating a large body of literature in recent years. The transfer of generated scientific knowledge to the business sector shows the increasingly frequent application of sensory marketing techniques in commercial establishments. Specifically, marketing managers use different techniques to improve the consumer experience through their senses. In other words, the practice of traditional visual merchandising is being cannibalized by seductive merchandising, which involves more than one sense, improving the consumer's sensation at the point of sale.

In the case studied in this work -although it should continue to be developed by expanding the study sample- it can be concluded that there is room to improve the implementation of marketing of the senses in fashion establishments. The application of different actions that stimulate the senses and that not only attract the consumer to the commercial establishment but also ensure that the sensations, feelings, and perceptions that these provoke in them turn their buying process into an attractive and exclusive experience should continue to be promoted. Only in this way, will they be in a better position to beat online sales.

REFERENCES

AUTHOR/S

Pedro Pablo Marín Dueñas

Ph.D. in Social Sciences from the Universidad de Cádiz. Assistant Professor in the Department of Marketing and Communication, in the Faculty of Social Sciences and Communication of the Universidad de Cádiz, he is the coordinator of the Degree in Marketing and Market Research and the double Degree in Marketing and Market Research and Tourism of the Universidad de Cádiz. He is a research member of the University Research Institute for Sustainable Social Development and Director of the University Radio INDESS Media Radio. His main line of research is communication in organizations, with more than 40 publications both in high-impact journals (JCR, SJR, ESCI) and in editorials indexed in the SPI.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8692-1174

Diego Gómez-Carmona

Ph.D. in Economic and Business Sciences from the Universidad de Granada. Interim Substitute Professor in the Department of Marketing and Communication, in the Faculty of Social Sciences and Communication of the Universidad de Cádiz. He is a research member of the University Research Institute for Sustainable Social Development and is part of the INDESS Research Commission. His main line of research is consumer neuroscience. His most recent works have appeared in journals indexed in JCR, such as Physiology & Behavior or DYNA, and have been presented at international conferences such as AEMARK or the Hispanic- Lusitanian Congress of Scientific Management.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0146-5956

Agradecimiento

Our thanks to the research group SEJ-482 Social Innovation in Marketing of the Universidad de Cádiz.