Vivat Academia. Revista de Comunicación (2024).

ISSN: 1575-2844

DO INFLUENCERS VIEW THEMSELVES AS OPINION LEADERS? AN EXAMINATION OF INFLUENCERS AND SOCIAL MEDIA CONTENT[1]

¿Se puede considerar a los influencers líderes de opinión? Un repaso a los influyentes y los contenidos de las redes sociales

![]() Hüseyin Yaşa[2]: Independent Researcher. Turkey

Hüseyin Yaşa[2]: Independent Researcher. Turkey

![]() Haluk Birsen[3]: University of Anadolu. Turkey.

Haluk Birsen[3]: University of Anadolu. Turkey.

How to cite this article:

Yaşa, Hüseyin, & Birsen, Haluk (2024). Do influencers view themselves as opinion leaders? An examination of influencers and social media content [¿Se puede considerar a los influencers líderes de opinión? Un repaso a los influyentes y los contenidos de las redes sociales]. Vivat Academia, 157, 1-28. http://doi.org/10.15178/va.2024.157.e1545

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Proposed by Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet in the 1940s, the concept of opinion leadership emerged with the two-step flow model. It is essential to explore whether the traditional acknowledgment of the concept continues specifically for influencers in social media environments. Methodology: Adopting a mixed-method approach, this study employed an exploratory sequential design. Semi-structured interviews were administered with 12 influencers, and content analysis was conducted on the influencers’ accounts and content to corroborate the qualitative interviews. The study population comprises Instagram influencers, while the sample consists of 120 posts shared by 12 influencers selected through purposive sampling. Results: The results of this study demonstrate that the two-stage flow theory needs to be updated and adapted to the present day, that influencers see themselves as opinion leaders, and that influencers perceive themselves as opinion leaders as a result of interaction with their followers. In addition, despite their particular opinion leadership roles on their target audiences, influencers who are/are not qualified as opinion leaders were influenced by other influencers who are/are not opinion leaders and their target audiences and thus sought opinions. Conclusions: In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of considering the concept of opinion leadership continues from its traditional acceptance, specifically for influencers who have a large audience on social media environments. Moreover, it was concluded that influencers must be evaluated by numerous factors, including social media usage practices, content, interactions with followers, and the level of communication with institutions, organizations, brands, or agencies, to mention their opinion leadership roles. The study was conducted within the context of a specific problem and limitations. The findings are expected to serve as a guide and contribute to other studies about the topic.

Keywords: Social media, Instagram, Two-step flow model, Opinion leadership, Influencers.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Propuesto por Lazarsfeld, Berelson y Gaudet en la década de 1940, el concepto de liderazgo de opinión surgió con el modelo de flujo en dos etapas. Es esencial explorar si el reconocimiento tradicional del concepto continúa específicamente para los influenciadores en entornos de medios sociales. Metodología: Adoptando un enfoque de métodos mixtos, este estudio empleó un diseño secuencial exploratorio. Se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas a 12 personas influyentes y se llevó a cabo un análisis de contenido de los relatos y contenidos de las personas influyentes para corroborar las entrevistas cualitativas. La población del estudio está formada por influencers de Instagram, mientras que la muestra consta de 120 publicaciones compartidas por 12 personas influyentes seleccionados mediante muestreo intencional. Resultados: Los resultados de este estudio demuestran que la teoría del flujo en dos etapas necesita ser actualizada y adaptada a la actualidad, que los influencers se ven a sí mismos como líderes de opinión, y que los influencers se perciben a sí mismos como líderes de opinión como resultado de la interacción con sus seguidores. Además, a pesar de sus particulares funciones de liderazgo de opinión sobre sus públicos objetivo, los influencers que son/no son calificados como líderes de opinión se vieron influidos por otros influencers que son/no son líderes de opinión y por sus públicos objetivo y, por tanto, buscaron opiniones. Conclusiones: En conclusión, este estudio pone de relieve la importancia de considerar el concepto de liderazgo de opinión continúa desde su aceptación tradicional, específicamente para los influencers que tienen una gran audiencia en entornos de medios sociales. Además, se concluyó que los influenciadores deben ser evaluados por numerosos factores, incluyendo las prácticas de uso de los medios sociales, el contenido, las interacciones con los seguidores y el nivel de comunicación con las instituciones, organizaciones, marcas o agencias, por mencionar sus funciones de liderazgo de opinión. El estudio se llevó a cabo en el contexto de un problema específico y con limitaciones. Se espera que las conclusiones sirvan de guía y contribuyan a otros estudios sobre el tema

Palabras clave: Redes sociales, Instagram, Modelo de flujo en dos pasos, Liderazgo de opinión, Influencers.

1. INTRODUCTION

The impact of messages conveyed through mass media on individuals’ attitudes and behavior has long been a research interest. During the 1940 US General Elections, the Columbia University Foundation and the Bureau of Applied Social Research conducted the first research on the role of mass media in voting behavior and election campaigns in Erie County, Ohio, USA. Starting from 1940 to 1944, Paul Felix Lazarsfeld, Bernard Berelson (1912-1979), and Hazel Gaudet (1908-1975) published their research in a book called The People’s Choice (1944) (Tokgöz, 1977, p. 88). Later, Lazarsfeld, Merton, and Mills (one of the famous sociologists of the period) (1955) conducted Personal Influence, the second significant research. However, since Mills left the research, Lazarsfeld and Katz wrote and compiled the results into a book (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955). Finally, Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee conducted a voting study about the presidential campaign in Elmira, New York, in 1948 (Berelson et al., 1954).

The Two-Step Flow model, developed by Paul Lazarsfeld and his research team between 1940 and 1948, and the first data on opinion leaders based on it were used in the Erie study that determined the impact of mass media on individuals’ voting preferences in the US presidential elections. Researchers found no direct impact of election campaigns through mass media on individuals’ voting attitudes and behaviors. However, they indicated the effectiveness of information individuals received from others they trusted or whose opinions they accepted (Lazarsfeld et al., 1960; Katz, 1957, p. 63). Opinion leaders might, therefore, be claimed to be actors with great power over the communication network (Lewis, 2009, p. 338). They can influence and direct individuals or groups to a certain extent and use this power if consulted about any issue (Bourse and Yücel, 2012, p. 86). They are considered by opinion seekers to be knowledgeable and trusted for their expertise on a particular topic (Weimann et al., 2007, p. 174). In this context, the two-stage flow theory specifically emphasizes four key characteristics of influence: (i) having followers, (ii) being considered an expert by opinion seekers, (iii) being knowledgeable about issues, (iv) being in a position within their local communities to exert social pressure and provide support on any issue (Dubois and Gaffney, 2014, p. 1263).

Katz (1957, p. 73) explained the distinctive aspects of opinion leaders using three criteria. The first includes who the opinion leaders are, their values, and personality traits. The second covers their competence in a particular subject and the content and amount of their knowledge. The last one encompasses their strategic position in their social circle, the people they interact with within or outside the group in society.

Due to their various functional characteristics, researchers have named opinion leaders trustworthy, innovators, thought leaders, trendsetters, prominent figures, influencers, and opinion givers (Black, 1982, p. 170). With their extensive knowledge about specific products or activities, opinion leaders often promote word-of-mouth communication. They also filter and comment on product- and brand-related information for their families, friends, and colleagues (Schiffman and Wisenblit 2019, p. 223-224). They use different sources of information (e.g., store visits, fashion, and various category-specific newspapers, magazines, etc.) compared to opinion seekers (Shoham and Ruvio, 2008, p. 293; Polegato and Wall, 1980, p. 337). Qualified opinion leaders tend to be technical experts in using high-tech products. They can also offer positive and negative objective opinions, as well as those based on subjective experiences (Shoham and Ruvio, 2008, p. 291; 294). Opinion leaders who specialize in their spheres of influence are more exposed to mass media and have a higher socioeconomic status than opinion seekers because they are media-savvy (Rogers, 1983, p. 282; Summers, 1970, p. 182). They have rich life experiences, and many are highly educated. They also have strong social skills and a good reputation for building strong professional connections with large audiences. They further have significant influence and attractive power. In addition, they are highly responsive to information and willing to adopt new things through innovative behavior (Huang et al., 2017, p. 181). When providing information about products, they confidently give advice and make personal assessments. They are sociable, determined, ambitious, dynamic, collaborative, open-minded, and open to innovations, thanks to their willingness to speak in front of a group and take risks (Myers and Robertson, 1972, p. 41;43; Li and Du, 2011, p. 190; Qiang et al., 2021, p. 1). It is also essential for them to have strong motivation and passion for what they do and be listener-centered and honest (Ratasuk, 2019, p. 37). Moreover, some of the important roles of opinion leaders in society are that individuals who can be characterized as opinion leaders by their social circles play an active role in political activities such as rallies, protests, and town meetings, as well as signing petitions, donating money, and volunteering (Tsang and Rojas, 2020, p. 763).

Based on the various opinion leadership roles identified in the literature, individuals traditionally described as opinion leaders convey their ideas, feelings, thoughts, behaviors, and attitudes to other individuals through traditional mass media, in addition to communicating face-to-face with other members of society. However, advanced information and communication technologies have transformed traditional opinion leadership, channeling it into different digital environments. As an outcome of digitalization, social media has provided opinion leaders with a new environment independent of time and space, bidirectional, easy, fast, practical, and interactive, and has altered and transformed various traditional practices. Social media has, therefore, differentiated the two-step flow model and created environmental shifts between traditional and digital opinion leaders, adding a new dimension by setting grounds for some differences in the practices of opinion leaders. From this perspective, the research problem arises at this point. It causes us to question whether the assumptions of the concept of opinion leadership, emerging with the two-step flow, are valid on social media and how and for what reason opinion leaders manifest themselves in social media environments.

Relevant studies in the literature focused on the impact of internet celebrities or influencers, described as digital opinion leaders on social media, on users and their role in users' purchasing attitudes and behaviors in social media marketing. In addition, the survey method was preferred to narrow the samples and obtain mainly quantitative findings. Therefore, this study differs from others for it provides explanations and comments by obtaining qualitative and quantitative data rather than just quantitative findings.

One of the primary purposes of the study is to understand how the concept of opinion leadership, emerging with the two-step flow model, has altered and transformed the influencers in social media environments thanks to advancing information and communication technologies. Thus, concerning traditional opinion leadership, assumed to have changed and transformed in social media environments, the study aimed to determine the similarities and differences of the concept and tackle it with influencers' content. Another aim is to determine whether influencers on social media might be considered opinion leaders by focusing on their social media usage practices. The following questions were addressed in line with the purpose of the study:

RQ1. How has traditional opinion leadership altered and transformed with social media?

RQ2. What are influencers' perceptions and experiences regarding opinion leadership?

RQ3. Do influencers perceive themselves as opinion leaders?

RQ4. What is the relationship between influencers and opinion leadership?

RQ5. In the context of opinion leadership, can influencers be considered as opinion leaders within their social media usage practices and content?

2. LITERATURE REVIEW AND OBJECTIVES

Initial data on the two-step flow model and opinion leaders came from the "Erie" study conducted by Paul Lazarsfeld and his team to determine the effects of mass media on individuals' polling preferences during the presidential elections in the USA between 1940 and 1948. Researchers found that election campaigns carried out through mass media did not directly impact individuals' polling attitudes and behaviors but that the information individuals received through other individuals they trusted or whose opinions they accepted did (Lazarsfeld et al., 1960; Katz, 1957, p. 63).

Opinion leaders have played a key role for voters less interested in election campaigns by providing individuals with information and opinions on political issues, candidates, and elections in general. In this context, the two-step communication flow in political campaigns takes place in two steps: (1) Opinion leaders are closely involved in media-transmitted political campaigns and get a good grasp. (2) They then inform and influence, by word of mouth, individuals who have not directly encountered the political candidates’ messages (DeFleur and DeFleur, 2022, p. 178-179; Katz and Lazarsfeld, 1955, pp. 32-35).

Today’s advancing technological opportunities have expedited the digitalization of opinion leaders, integrating them with social media environments within interactive socialization and online circles. Therefore, digital media environments have changed the communication and social structure of those seeking opinions of opinion leaders and impacted their thoughts and behaviors about individual or social phenomena. Consequently, opinion leaders, time- and space-bound in conveying messages in traditional media to opinion seekers, have found a more comfortable, efficient, and faster communication environment online in social media environments.

Individuals described as the new opinion leaders of the digital society are social media influencers. Brown and Hayes (2008, p. 50) define an influencer as a third party with a significant influence on and is responsible for consumers’ purchasing decisions. Some studies showed that influencers not only impacted consumers’ purchasing behavior and preferences but also their expectations (Anderson and Salisbury, 2003, p. 115), their attitudes before using any product (Herr et al., 1991, p. 456), and even their post-usage perceptions (Bone, 1995, pp. 221-222) of a product or service (Jalilvand et al., 2011, p. 43; Knoll and Proksch, 2017, p. 1). Consumers do not perceive social media influencers as more reliable than celebrities, yet they think that influencers become more identified with their followers and strongly impact their purchasing behavior (Schouten et al. 2020, p. 258; Pop et al., 2022, p. 837). Influencers might additionally take on new roles as persuasive agents, opinion leaders, brand supporters, and role models in the communication environment of their followers (Kühn & Riesmeyer, 2021, p. 67). Furthermore, influencers, like opinion leaders, mediate the dissemination of any innovation by sharing it with users in social media environments. Innovation is one of the most significant factors that determine impact intensity. At this point, in addition to having a more central network position, influencers might be claimed to have more accurate information about a new product, are less sensitive to norms, and tend to exhibit innovative behavior (Saad et al., 2018, p. 1804; van Eck et al., 2011, p. 187).

With their traces in every aspect of our daily lives, social media environments have become the most common digital communication areas. These new types of opinion leaders created by social media stand out with the content they create among millions of users in the virtual space. They are described as “internet celebrities or influencers,” with a certain number of followers as the representatives of traditional opinion leaders in social media environments and the potential to influence the target audience with their ideas, experience, and recommendations.

One of the main objectives of the research is to understand how the concept of opinion leadership, which emerged as a result of the two-stage flow model, has been transformed and transformed by influencers manifesting in social media environments thanks to the developing information and communication technologies. Thus, the research aims to indicate that the concept, which has undergone digital transformation and change from traditional opinion leadership, is handled within the framework of different concepts in social media environments, and to identify and discuss some different and similar points. Another aim is to focus on whether influencers manifested in social media can be evaluated as opinion leaders and their social media usage practices. Because it will be possible to define digital opinion leadership, which is explained in social media environments and concepts different from the traditional meaning, by considering whether influencers see themselves as opinion leaders, their social media usage practices, their level of interaction with their followers, their online behaviour patterns, the social media language they use and the content of their accounts.

3. RESEARCH METHOD AND DESIGN

The study adopted a mixed methods research model in which qualitative and quantitative analysis methods and tools were employed to answer the questions created in line with the research problem and objectives. Mixed method research designs are classified with different names. In general, designs are classified in three ways according to data collection and analysis: ‘convergent (parallel) design’ ‘explanatory sequential design’ and ‘exploratory sequential design’ (Creswell and Creswell, 2018, p. 52; Creswell and Plano Clark, 2015, p. 391). An exploratory sequential design was deemed appropriate for this study.

This study embraced phenomenology (the science of subjective experience), one of the qualitative research designs, to understand and interpret the life world of influencers and get to the heart of their experiences. Concerning the phenomenological distinction (descriptive/interpretive), the “interpretive phenomenology” pattern was preferred in line with Heidegger’s approach. The study adopted Heidegger's interpretive phenomenological approach because it brackets itself, as done in Husserl's descriptive phenomenological approach. Put differently, the desire to actively participate in a relational interpretation process with the concepts of opinion leadership and influencers that the researcher is interested in, rather than an objective approach, has been the main factor in choosing the interpretative phenomenological approach.

While the population of the study’s qualitative dimension consisted of social media influencers, the sample comprised 12 different Instagram influencers (Fashion, Beauty, Health, Food, Life, Media, Sports, Tourism, Travel, Education, Gaming, and Technology) selected through purposive sampling method. On the other hand, the population of the quantitative dimension consisted of Instagram influencers, while the sample comprised ten posts selected from the Instagram profiles of 12 influencers (i.e., 120 posts in total) chosen by purposeful sampling method, one of the non-probability sampling types. These 120 posts were selected to collect much richer and more in-depth information because they were relevant to the research topic and in line with the nature of phenomenological research. The posts were collected from influencers’ accounts between 13-17 April 2023. In addition, while selecting ten posts from 12 influencers, the content related to the Kahramanmaraş earthquake that occurred in Turkey on February 6, 2023, retrospectively from when the semi-structured interviews were completed (March 1, 2023), was not included in the study. We did not include them so they would not impact the research, as influencers’ interactions and sharing practices on social media (Instagram) varied during these periods.

Qualitatively, the study utilized a semi-structured interview technique, one of the data collection techniques frequently employed in phenomenological research. While preparing the interview form, the literature was scanned, and a pool of interview questions was created in the first stage in line with the data in the literature. The initial question pool had 75 questions. The supervisor, faculty members in the thesis monitoring committee, and other experts in the field examined those questions. As a result of the review, some experts suggested removing some questions, while others advised adding new ones. They also made constructive criticisms and suggestions regarding the order and wording of the questions. In the last stage, the semi-structured interview form was created based on the necessary corrections and changes to the questions selected from the initial pool and finalized under the advisor’s control. This research technique was chosen because new questions could be asked in addition to the prepared questions, and the questions could be replaced, thus creating flexibility. This technique also promoted answers with fixed options and in-depth answers related to the research.

Quantitatively, content analysis was conducted, following the stages of coding the data, determining the themes, arranging the codes and themes, and defining and interpreting the findings (Yıldırım and Şimşek, 2016, p. 243-244). The coding table created for content analysis resembles the survey form. It contains a list of variables that can be used to code a small research unit, such as each publication, article, paragraph, or sentence. For each variable, there are values or coding options associated with the variables (Hansen, 2003, p. 84-85). Accordingly, before conducting content analysis on the Instagram profiles and influencers' content, a coding table was created based on the literature review and the characteristics of the Instagram platform. Careful attention was paid to ensure that the coding table created both supported and validated the semi-structured interviews and could reveal the profiles, content, and interactions of Instagram influencers.

For the study's data analysis, 235 pages of data were obtained by transcribing the interviews of influencers in 12 different categories interviewed within the sample to access qualitative data in the first stage. The analyzed data were transferred to the "MAXQDA" and "NVivo" qualitative analysis programs. Themes and codes were then identified using the analyzed data. The determined themes were then associated with the data obtained. By reducing the themes, relevant data were handled under the same code, or higher codes were created, and data were included in these codes. Within the framework of qualitative research, a total of 560 codes were made in the MAXQDA program. In the second stage, after creating the coding table for content analysis to access the quantitative data analysis, the themes in the coding table were transferred to the MAXQDA program. Later, under the themes transferred, ten posts of the 12 influencers were coded into the created themes using the coding table. The MAXQDA program created 3566 codes within the framework of quantitative research. Frequency analysis, one of the content analysis techniques, was used to analyze the data according to repetition and frequency or number and percentage ratios.

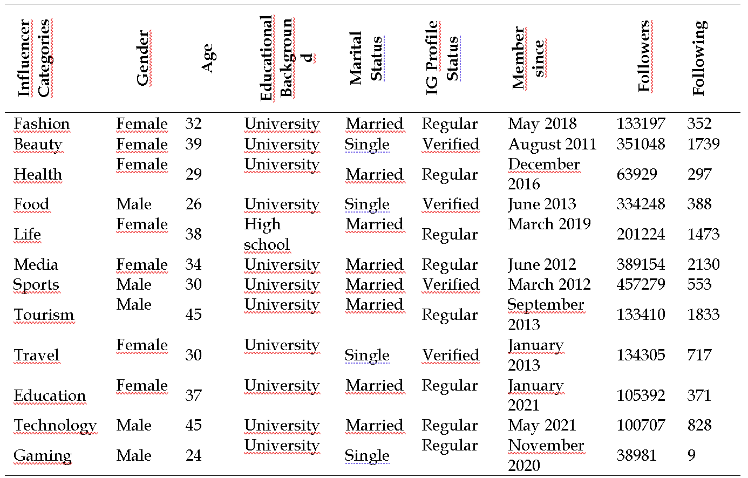

Information about the study’s sample (participants) is given in Table 1:

Table 1

Information about participants.

Source: Own elaboration.

Within the framework of the decision made by Eskişehir Anadolu University Social and Human Sciences Scientific Research Ethics Committee at its meeting dated 24/01/2023, protocol number 464885, the study does not involve any ethical drawbacks.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Qualitative analysis findings

4.1.1. How influencers define and explain opinion leadership

When asked how they defined opinion leadership, what opinion leadership was, and what they knew about it to learn the influencers’ perceptions and experiences regarding opinion leadership, the desired answers could not be obtained. This might stem from the infrequent use of the opinion leadership concept today. For that reason, participants were told briefly about the opinion leadership concept for better understanding and later asked to provide a definition and explanation.

The fashion influencer defined opinion leadership as “accepting an idea and passing it on to others so they can benefit from it as well.” She mentioned that an opinion leadership role requires influencers to tell their followers about the products they personally used and experienced, develop purchasing behaviors, and ensure they benefit from them.

The beauty influencer defined opinion leaders as “people who can serve as a model to people in their profession or view of life, who can be people’s idols, who have ideas or thoughts that can have a motto - these thoughts can be conveyed with sentences, articles, etc. - and people who are leaders or are considered leaders.” She also stated that influencer opinion leaders should be experts in their fields and have the potential to influence individuals with their thoughts.

Stating that influencers must influence people about their profession to assert that they are opinion leaders, the beauty influencer argued that if they assumed such an opinion leadership role from another field, it would fail. Declaring that she did not have an opinion leadership role in a field other than her own and that she had been posting about make-up for years, she expressed her thoughts about opinion leadership by saying, “I hope I am,” rather than claiming specifically that she owned an opinion leadership role. Defining opinion leaders as “individuals who follow the agenda with their knowledge and experience or who have an opinion on common issues that concern society, not personally, and who have the influence to take action,” the education influencer explained this concept with various examples.

Modern-day influencers, according to the education influencer, are sent products by specific brands and paid for trying them and narrating their experiences to their followers, which she thought was not objective because influencers read the given text for a fee and conveyed information about an unfamiliar product. She underlined that opinion leadership cannot be spoken of in such cases. Therefore, stating that she left individual work and her role as an opinion leader when financial situations came into play, the education influencer mentioned that she already had a source of income and had no financial concerns. The role of influencers as opinion leaders cannot be associated with any financial concerns. Even their content's disapproval or reaction by their followers is, in this regard, likely to increase. Influencers might thus have to set aside their financial concerns and convey the product they have experienced and trusted. While the education influencer also mentioned that influencers in Turkey were influencers and had a source of income even when they were jobless, she argued that if IG were to close down today, they would not be able to apply for a job because they did not have a resume regarding their work background.

Viewing opinion leadership as a psychological concept, the health influencer mentioned that they (IG influencers) also served as opinion leaders if individuals acquired ideas about products or services after their posts, used them, wanted to experience them, and influencers had a specific impact on individuals and shaped their perceptions:

In fact, I think it is a bit more of a psychological concept. We can also call it perception management in people’s minds. For example, if people get an idea about a product or a service through a post of mine and want to use and experience it, if I can influence them and help shape their perceptions, then, in my opinion, I serve as an opinion leader (Health Influencer).

Pointing out that individuals who have adopted a specific philosophy regarding opinion leadership and have a purpose can reach opinion leadership from being an influencer, the food influencer stated that only a minority served a particular purpose: “People who have already adopted a philosophy and purpose can reach opinion leadership from influencers. However, since influencers are usually young people, homemakers, or celebrities, perhaps only one or two percent serve a specific purpose.” Mentioning that being a doyen means opinion leadership, the tourism influencer declared that individuals could be opinion leaders in different fields, such as politics, sports, and the economy: “You know, doyen actually means a bit of an opinion leader. This is true in politics, the sports community, and the economy. Therefore, this applies to me and the tourism community as well.” (Tourism Influencer). In addition, the tourism influencer stated that not every influencer could be an opinion leader. However, some influencers could be opinion leaders, and he said he followed opinion leader influencers who touched his life, whom he respected, who liked the way he expressed himself, and whose opinions he attached importance to, although it did not matter whether their ideas were similar:

Not every influencer is an opinion leader. But some influencers are. (...) I often try to follow influencers who are opinion leaders. In other words, it does not matter if we have similar views, and they will touch my life, but I definitely follow opinion leader influencers whose views I respect and whose way of personal expression I like. (Tourism Influencer)

Influencers share on social media for various reasons, such as financial gains or the influence of a good status gained in that environment. Similarly, the target audience of influencers can follow to obtain information about products or services. For a better connection between the two situations, influencers must convey to their followers the products they have experienced and used, especially in health. Therefore, it might be inferred that influencers cannot have an opinion leadership role in conveying false information to their target audience about a product or service that they are not sure about due to financial concerns.

Expressing ideas about the appropriateness of the environment, conditions, and circumstances to achieve the opinion leader qualification, the gaming influencer compared social media platforms. Thanks to the opportunities offered by social media platforms, individuals’ potential to express themselves is likely to diversify and increase. Based on the statements, they can promote ideas through virtual environments where influencers and other users can provide opinion leadership, with some trapped in a spiral of silence by hesitating to express their opinions.

Comparing traditional and social media opinion leaderships, the influencer viewed herself as an intermediary in social media environments because influencers cannot serve the traditional role. The media influencer associated her potential to be an opinion leader with her mastery of the subject:

Previously, it was a politician or a journalist on a radio or a television channel. But now, of course, we can never be as good as them, but we are intermediaries. The more I master the subject, the more I can be an opinion leader because I will know what should be conveyed, how it should be conveyed, and where attention should be drawn. That is why I think it is essential for us to be well-equipped in this regard. (Media Influencer)

Mentioning that opinion leadership was a serious responsibility, the media influencer explained that this situation occurred in various ways in media, giving an example from a project she participated in. She also underlined the need to introduce a city not unidirectionally but from many different perspectives.

Described as opinion leaders, influencers are network actors playing a significant role in changing the behavior and attitude of users and other influencers. Unlike other users, influencers have the potential to significantly impact attitudes and behaviors thanks to their particular position within the network for their field. Therefore, exhibiting innovative attitudes on social media concerning their fields indicates that influencers have, to some degree, an opinion leadership role because they have guided users and other influencers in their fields as decisive role models in the social network:

(...) If you are doing something for the first time in your sector, people will be inspired by you and may think, "Look, he is doing something right. He is at this point now." They can follow you and imitate you, with respect for your work. (...) Frankly, I can say that I have become somewhat of a leader in the industry so far. (Sports Influencer)

4.1.2. The state of opinion leadership perceptions among influencers

To determine whether influencers viewed themselves as opinion leaders, they were asked, “Do you perceive yourself as an opinion leader on social media?”

4.1.2.1. Influencers viewing themselves as opinion leaders

Stating that she viewed herself as an opinion leader, the fashion influencer declared that she acquired this perception based on people’s reactions in daily life outside the social media environment. Similarly, the beauty influencer asserted that she had been very active in her field for a long time, claiming that while sharing her experience with a product or service to her followers, she first experienced and used it herself. Therefore, she mentioned that she viewed herself as an opinion leader within the framework of these social media practices.

Influencers in the same fields might not share their experience and knowledge with others to make more financial gains. However, the education influencer stated that she viewed herself as an opinion leader and shared her knowledge and experiences in her field with her target audience and other influencers. In addition to mentioning her role as an opinion leader in certain situations, she associated opinion leadership with seeking the knowledge of other users.

Viewing herself as an opinion leader, the media influencer mentioned that she first experienced every product he promoted and then shared it with other individuals, accordingly, having the role of an opinion leader by conveying her experiences and knowledge about the places she visited to people through various newspapers.

Establishing sincere bonds with her followers, the influencer expressed the positive feedback received after promoting any product. The influencer mentioned her role as an opinion leader because of a particular impact on her target audience:

I see (myself as one). But of course, I will still be modest about this. Since I follow the language and habits of the people, I tell it as if I were telling it to my family. For example, less than five minutes after introducing a product, if anyone has used it before, they write down their opinions. They write about how satisfied they are. They also write if they do not like it and want me to convey the brand. I try to help in any way I can. I must say I consider myself an opinion leader in this regard as well. (Life Influencer)

Mentioning her role as an opinion leader for her target audience in the last year, the health influencer stated that she took a break from social media for a while and later received positive feedback from her followers after actively sharing. She emphasized that she had such an opinion leadership role, for she created positive attitudes and behaviors in her interactions with her followers:

I can say that I consider myself an opinion leader for the last year because I took a break from social media for nearly two years. Later, when I started using it actively, I realized people contacted me even for a post I shared casually when I first opened my account. So, I could add something to people, change their perceptions, or draw their attention. If we can go back and interact even about this, I think it means I can make an impact on them (Health Influencer).

Considering that she had a specific opinion leadership role on her followers, the travel influencer also stated that she viewed herself as one: So yes. I think I am. I believe I have a specific opinion leadership role among my followers. (Travel Influencer)

4.1.2.2. Influencers that do not view themselves as opinion leaders

Stating that it is essential to get closer to people to have a specific opinion leadership role, the food influencer stressed the necessity of instilling ideas in followers through close interactions. Therefore, influencers establishing sincere relationships with their target audience must also gain, in part, confidence in creating specific behaviors and attitudes among them. Considering that not everyone would agree with the ideas expressed by the influencer, he claimed not to have a specific opinion leader role or view himself as one:

I do not view myself as an opinion leader. I do not think I have a specific opinion leadership role or purpose because I must be closer to people to have that role. I must be more intimate and instill an idea in them. That specific idea, way of thinking, or event may not appeal to everyone. I am not a fan of people's negative comments when expressing their opposing views. So, I avoid such issues. (Food Influencer)

4.1.2.3. Influencers who are indecisive about their opinion leadership roles

Not considering himself an opinion leader, the technology influencer declared that he received many messages from his target audience. Since he had no clear statement such as “Yes, I view myself as an opinion leader” in his remarks on opinion leadership, his comments were tackled under this heading in order not to position it anywhere:

So, I never thought of myself as an opinion leader. But I get a lot of questions through DMs from my followers on my IG account: "Bro, I am going to buy a phone. What should I buy? They even send sincere messages. "Hey, chief/king, I intend to buy a speaker. What should I buy? I am considering buying this. Would you recommend it?" Or "Chief, I need something like this. What should I buy?" A lot of questions pop up. I make recommendations to the best of my ability. (Technology Influencer)

Reluctant to put himself in a specific mold when asked whether he had an opinion leadership role, the sports influencer answered the question we asked considering his target audience: “I can say they view me so. I do not want to put myself in such a mold. I am like this, or I am like that.” (Sports Influencer). Similarly, the tourism influencer believed he did not even call himself an influencer. He thought he was close to such an opinion leadership role because he was referred to as an influencer and doyen at the events he attended:

Indeed, I have never called myself an influencer until now. But I have been called the tourism doyen, a tourism influencer, a prominent figure in tourism, and a name with respected opinions for almost the last five years when I was announced or called somewhere. All this suggests we have already come close to the definition of opinion leadership. (Tourism Influencer)

Declaring that he could be an opinion leader in his field, the gaming influencer held that this was proportional to the influence of his account. Comparing social media users who received different interactions, the influencer argued that the influence of users with lots of interaction might differ from that of opinion leaders with little interaction. Evaluating that hundreds of thousands of people can simultaneously access a post thanks to the dissemination feature of social media platforms, the influencer emphasized that his posts, events, or situations might generate perceptions and attitudes among large masses.

4.1.3. Influencers’ opinion leadership status in the eyes of followers

The study also aimed to obtain influencers' views about their followers other than solely their perceptions and experiences of whether they viewed themselves as opinion leaders. To that end, the participants were asked, “Do you believe your followers regard you as an opinion leader on social media? Can you explain?” In doing so, we focused on discovering the perceptions and experiences of the target audience about whether they regarded influencers as opinion leaders. Based on their observations of their followers, it, therefore, becomes essential to infer why influencers consider themselves opinion leaders or why they are not one.

Believing that their target audience viewed them as opinion leaders, the fashion and beauty influencers explained this perception and experience through their followers' questions. Followers applied to the fashion influencer’s knowledge by asking about the clothes they would wear in everyday life. Similarly, the beauty influencer received positive feedback from her target audience for conveying information about the product or service, indicating the need for her thoughts and guidance. For these reasons, the two influencers thought their follower viewed them as opinion leaders.

Thinking that her followers viewed her as an opinion leader because they consulted her ideas and submitted them for approval, the life influencer mentioned that they expected her to convey her thoughts, ideas, and experiences:

I believe they see me as one because getting my opinion and submitting it to my approval makes me think they do so. In other words, they want you to convey at least one of your ideas, thoughts, or, I do not know, your experiences. They ask questions, and I like that. (...). (Life Influencer)

Influencers can engage in attitudes and behaviors that aim to develop a particular understanding of innovations in products or services, reduce the uncertainty of their target audience, or diminish anxiety due to complex thoughts. These attitudes and behaviors are very motivating to ensure the target audience's trust in the influencers and maintain healthy interactions. To better explain this situation, the food influencer’s remark reads: Obviously, my people see me that way because, for example, if (...) shares something, they buy the product, thinking it is good and there is nothing to worry about. Since I have personally experienced the products, I think they inevitably see me as one. (Food Influencer). This shows that the content is consumed without considering it good or bad because she has gained her target audience's trust after sharing content. This, in turn, causes influencers to infer that their followers view themselves as opinion leaders.

Since influencers are considered knowledgeable on specific topics and fields (Nisbet and Kotcher, 2009), their advice or guidance for their target audience is considered valuable. For this reason, the influencer stated that he received a lot of questions from his target audience, claiming that they saw him as an opinion leader: I get a lot of questions, both via DM and under my posts, about what to buy. So, they see me as an opinion leader because they need my ideas and guidance on some topics and products (Technology Influencer). Based on the same thoughts, there is a perception that the travel influencer viewed her as an opinion leader based on her followers' messages, e-mails, or interaction styles. Additionally, it was mentioned that followers who wanted to consult the influencer's opinions, especially in times of crisis, constantly asked questions on topics or areas of interest. This, in turn, led to the perception that influencers considered themselves opinion leaders: Yes, I think they do, because especially in times of crisis, they ask me for comments and opinions on this subject. Almost every day, many people ask questions about his business life or career in the tourism industry (Tourism Influencer). Accordingly, followers who seek influencers' opinions and experiences regarding their daily life problems, not only in connection with social media environments, might view them as a solution at some point. Based on these inferences, the education influencer also stated that she thought her target audience saw her as an opinion leader. In addition, offering thoughts on how not only the influencers’ target audiences but also other influencers in their fields viewed influencers as opinion leaders at some points, the sports influencer stated that the online coaching system in his field was an important determinant. Therefore, at some point, influencers also serve as a role model for their followers and other influencers in their field. An innovation claimed by influencers in their field might also, to some degree, impact attitudes and behaviors, depending on individuals' interests. This can create considerable potential, especially for improving purchasing behavior.

Regarding her role as an opinion leader in the eyes of her followers, the health influencer established a connection about her IG profile management and mentioned that after sincerely sharing posts about truly accurate products or services without a commercial purpose, individuals engaged in purchasing behavior regardless of her next post. Therefore, when opinion seekers (followers) decide on a product or service, they might rely on the knowledge and experience of influencers, thinking that it would be a great option in cases where they are not sure at this decision-making stage. At this stage, however, they must make the right decision by not directly believing what the influencers say and researching the products or services.

4.2. Quantitative analysis findings

4.2.1. Account types of influencers associated with opinion leadership

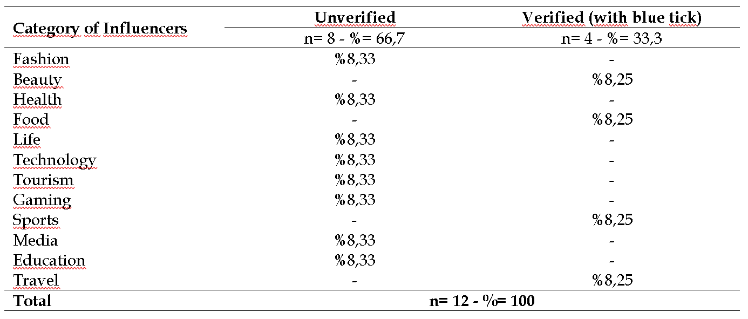

Table 2

Status of influencers’ İg accounts (Regular/Verified).

Source: Own elaboration.

Badges acknowledged as “Verified Account” help understand that IG accounts are opened and managed by real individuals and indicate that user accounts are reliable and belong to a well-known person, celebrity, institution, organization, or brand. Obtained on IG by relevant persons, institutions, organizations, or brands with or without applications in some periods, the blue tick is easily recognized by users, allowing them to distinguish fake accounts opened in the name of persons, institutions, organizations, or brands and helping users to access original accounts easily. Findings about influencer account types (regular and ticked (verified) revealed that fashion, health, life, technology, tourism, gaming, media, and education (n = 8/66.7%) accounts were regular, whereas beauty, food, sports, and travel (n=4/33.3%) accounts were verified.

Despite the lack of a direct connection between opinion leadership and the blue tick, if an individual is viewed as an opinion leader on social media, that person does not need one. Likewise, an IG user with a blue tick may not be regarded as an opinion leader. The criterion of being an opinion leader is directly or indirectly related to the influence of an individual or individuals on other users. In this case, individuals must be evaluated using such criteria as expertise on the subject, accuracy, reliability, respect in society, etc., within the framework of an opinion leadership role.

4.2.2. Location information of influencer accounts associated with opinion leadership

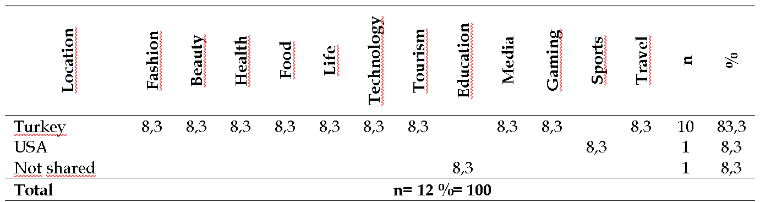

Table 3

Locations of influencer accounts.

Source: Own elaboration.

An analysis of the locational information of influencer accounts demonstrated that ten influencers (fashion, beauty, health, food, life, technology, tourism, media, gaming, travel; n = 10/83.3%) were from T, one influencer was from the USA (sports; n = 1/8.3%), and one influencer (education; n=1/8.3%) preferred not to share her location information. Influencers may or may not share their locations with the target audience. In this context, influencers with disclosed locations might be discovered by other users and provided with opportunities for nationwide and regional collaborations with institutions, organizations, and brands for their products or services. This is important, particularly for opinion leadership, for posts to be understood manifestly and the current location to be interpreted meaningfully along with its culture, history, etc.

4.2.3. Mention (@) use and content of influencers associated with opinion leadership

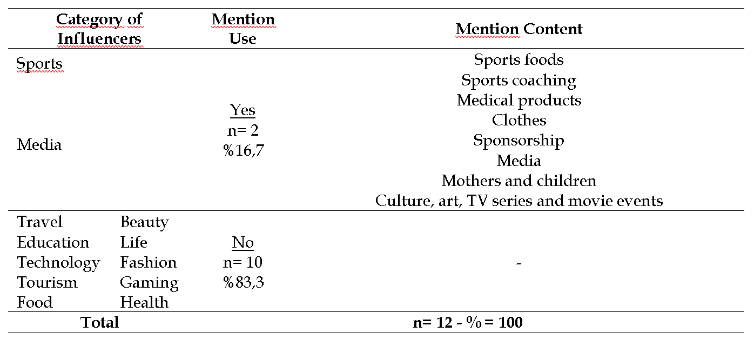

Table 4

Mention (@) use and content in influencer bios.

Source: Own elaboration.

An analysis of mentions in influencers' profile bios revealed that two influencers (sports and media) (16.7%) mentioned another person or brand, with no mentions of any person, institution, organization, or brand by other influencers (travel, education, technology, tourism, food, beauty, life, fashion, gaming, health) (83.3%). The mentions used by the sports influencer were related to sports foods, sports coaching, medical products, clothes, and sponsorship,” while those used by the media influencer were about media, mothers and children, and culture, art, TV series, and movie events.” Influencers' preference to use mentions in their bios is essential in providing information to their target audience about the products or services they use and announcing them to a broader audience. Using mentions also allows the target audience to directly communicate and interact with the institution, organization, or brand without reaching the influencer about the product or service they seek. This is especially important for influencers, described as opinion leaders, to provide information to and directly interact with their target audience about the products or services they have experienced, apart from their commercial concerns.

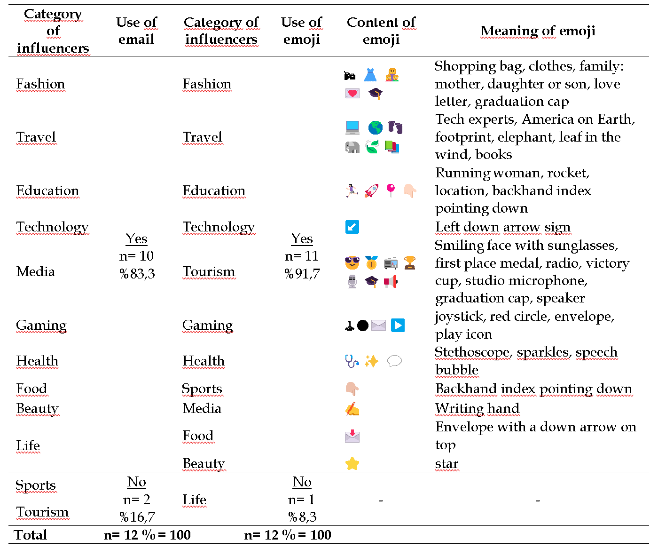

4.2.4. E-mail address usage, emoji content, and their meanings by influencers associated with opinion leadership

Table 5

Use of email address, emoji content and their meanings in influencers’ bios.

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 5 displays that some influencers (fashion, travel, education, technology, media, gaming, health, food, beauty, life) (83.3%) included e-mail addresses in their profiles, while others (sports and tourism) (16.7%) did not. User profile bios indicated that 91.7% of the influencers (fashion, travel, education, technology, tourism, gaming, health, sports, media, food, and beauty) used emojis, excluding one (life) (8.3%). Explanations regarding the content and meanings of emojis according to influencers are detailed in Table 5.10. In this context, it can be inferred that each influencer used a self-descriptive method on IG for their target audience.

Positive or negative feedback via the mail address of the target audience for the product or service promoted by influencers can positively contribute to eliminating the negativities caused by influencers or raising awareness in similar situations. Hence, influencers must include e-mail addresses in their profiles to establish interaction and communication with their target audience and institutions, organizations, or brands. It might also be critical for the target audience and institutions, organizations, or brands. Since the target audience of influencers is quite large compared to other social media users, many institutions, organizations, or brands contact via emails in most cases for collaborations. Thus, by providing information to influencers about their products or services via e-mail, institutions, organizations, or brands create a potential to increase their sales with the right, active influencers and target audience and create specific sponsorships to support influencers.

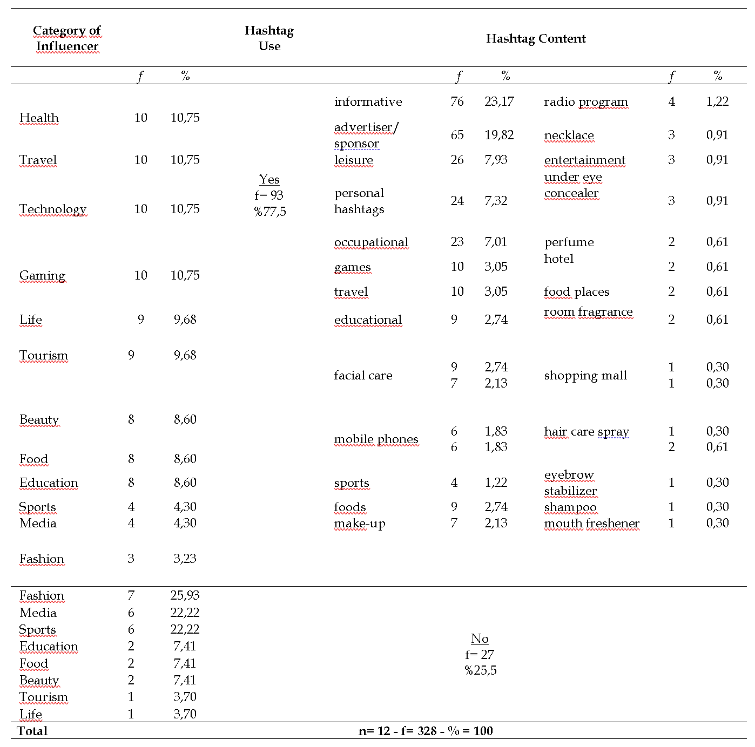

4.2.5. Hashtag patterns of influencers associated with opinion leadership

Table 6

Hashtag use and content in influencers’ posts.

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 6 displays hashtag content and usage frequency in the influencers' posts. The analysis showed that hashtags were preferred by 77.5% in 93 posts, while no hashtag was used by 25.5% in 27 posts. It was observed that health, travel, and technology influencers used hashtags the most (10.75%) in all their content, while the fashion influencer used them the least (3.23%) in three of her posts. The hashtag content included entertainment, mobile phones, make-up, foods, education, travel, games, sports, hotels, jobs, personal hashtags, radio programs, leisure, advertiser/sponsor, information, hair care sprays, eyebrow stabilizers, food places, under eye concealers, room fragrances, facial care, mouth fresheners, shopping malls, perfumes, and necklaces.

It is important for influencers, described as opinion leaders, to be included in such a hashtag system, especially compared to other users, as it allows them to be associated with a common ground in their field or with other users regarding similar interests. It might, therefore, be maintained that influencers using hashtags under any photos or reels can reinforce their opinion leadership role against users, institutions, organizations, or brands for their target audience and increase their interaction on IG. Indeed, using hashtags is crucial to reach a larger audience when sharing on digital media.

Supporting the research findings (Lycarião and Santos, 2017, pp. 368-385; Ardiyanti et al., 2022, pp. 36-56; Khan et al., 2017, pp. 1-6), various methods were presented to support the relationship and importance of hashtags with opinion leadership to identify opinion leaders accurately through hashtags in social networking environments. Therefore, different studies in the literature support this study.

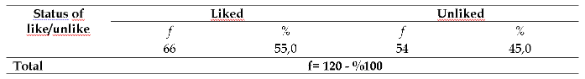

4.2.6. Comment interactions under the content of influencers associated with opinion leadership

Table 7

The status of liked comments by influencers under posts.

Source: Own elaboration.

Analyses revealed that 55.0% of the comments were liked in 66 of 120 posts, with 45.0% of the comments on 54 posts unliked by the influencers. Regarding the status of likes of user comments coded under the liked category, influencers did not hit the like button for all but liked most user comments. On the other hand, none of the comments under the influencer content in the unliked category were liked by the influencers.

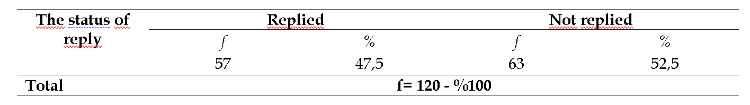

Table 8

The status of influencers’ reply to comments under posts.

Source: Own elaboration.

It was concluded that while 47.5% of the comments under 57 of 120 posts were replied to, 45.0% under 54 posts were not by the influencers.

The influencers’ replies to user comments regarding the content tackled in the study were examined. For the “replied” category, the influencers’ replies to users were considered and evaluated under the relevant category. In the “not replied” category, if the influencers did not reply to any users, they were evaluated by coding under the relevant category.

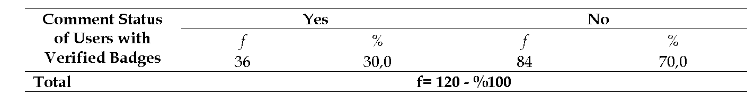

Table 9

Comment status of users with verified badges in comments under influencer content.

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 9 indicated that verified users commented under 36 of 120 posts (30%), while no comments from users with verified badges were found under 84 posts (70%).

The response status of influencers to users who comment on their content is crucial for making specific inferences about opinion leadership and understanding the interactions within IG comments. Regardless of whether one agrees with the users, replying to the content is significant as it contributes to forming active dialogues on the influencer's account and indicates that the comments are heeded by their target audience. Additionally, specific observations about the topic were made in the analyzed content. For instance, it was observed that influencers made specific statements to their followers and attempted to shape their thoughts in parallel with theirs or provided guidance on the subject when the comments under the posts were not understood by the target audience or adopted equally. Accordingly, when used positively, IG comments might create a relationship between influencers considered opinion leaders and their target audience to provide solutions to problems, establish interactions, and even be a considerable resource for the target audience.

5. CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

This study was conducted bearing in mind the understanding of how the concept of opinion leadership, emerging as a result of the two-step flow model, changed and transformed in social media environments thanks to developing information and communication technologies and the consideration of influencers' social media activities and their potential role as opinion leaders.

The following questions were addressed to determine the perceptions and experiences of influencers regarding opinion leadership, which formed the theoretical and conceptual basis for the study: “How do you define opinion leadership? What is opinion leadership? What do you know about this?” The desired answers could not be received from the influencers. This might stem from the limited use of the opinion leadership concept today. Therefore, during the interviews with the influencers, participants were briefed about “opinion leadership” for a better understanding of the concept and asked to provide a definition and explanation. Analyses showed that participants defined or explained opinion leadership using mostly such qualities and characteristics as “social, expert, knowledgeable, idol, doyen, responsibility, inspiration, young.”

Concerning their perceptions of their opinion leadership roles, influencers generally regarded themselves as opinion leaders because seven out of 12 (fashion, beauty, education, media, life, health, travel) reported they viewed themselves as opinion leaders. It was found that participants used such words as “influence, experience, perception, and attitude change” to express their views on opinion leadership. In addition, a participant who stated firmly that he did not view himself as an opinion leader voiced the necessity of a specific "intellectual instilling" for a potential opinion leadership role. Furthermore, five participants avoided positioning themselves strictly as opinion leaders and stated the following: I did not think of myself as an opinion leader (Technology Influencer), I do not want to put myself in such a mold (Sports Influencer), It means we are close to the definition of opinion leadership (Tourism Influencer), and In terms of gaming, of course (Gaming Influencer).

Participants were asked the following questions to find out whether their followers viewed them as opinion leaders within the framework of the influencers' perceptions and experiences: “Do you believe your followers regard you as an opinion leader on social media? Can you explain?” Thus, it is crucial to make certain inferences about whether or not their followers view influencers as opinion leaders based on their practices on social media. The following participant views led to the perception that the influencers regarded themselves as opinion leaders: (i) considering them field experts, (ii)requesting opinions, suggestions, or recommendations about any product or service, (iii) positive comments that were received, (iv) requiring the opinions and guidance of influencers and submitting them for their approval, (v) expecting that they would share their ideas and experiences, and (vi) the positive reactions from their followers through messages, e-mails, or other means as a result of pioneering work in their field. In this context, influencers also serve an opinion leadership role to a certain extent by taking an active approach to developing solutions to the inquiries of their IG followers. In fact, the stronger the bond within the network, the more considerable the impact potential of the influencers' opinion leadership role will be.

Research findings suggest that it would be erroneous to claim that IG influencers are literally opinion leaders or that their role as opinion leaders certainly exists. As the research findings indicated, influencers might be described as opinion leaders in some cases, while in others, it might not be possible to arrive at that conclusion. For that reason, it would be more appropriate to consider the influencer’s presence in social media environments, experiences, sharing practices, content, and followers to make such an evaluation. This is because of the disagreement between traditional and social media opinion leadership assumptions. Additionally, new types of opinion leaders integrated into social media environments with different concepts have changed and transformed traditional opinion leaders or assumptions of opinion leadership roles. Therefore, the concept continues to exist traditionally and virtually (on social media platforms). Furthermore, it would be fit to define and explain opinion leadership, different from its traditional meaning in social media environments, and determine individuals or groups by considering more criteria when determining opinion leaders or the role of opinion leadership in social media environments.

All in all, some of the significant findings were as follows: Influencers generally viewed themselves as opinion leaders. They also thought their followers regarded them as opinion leaders based on their interaction practices and experiences with their target audience on IG. In addition, despite their particular opinion leadership roles on their target audiences, influencers who are/are not qualified as opinion leaders were influenced by other influencers who are/are not opinion leaders and their target audiences and thus sought opinions. The study was conducted within the context of a specific problem and limitations. The findings are expected to serve as a guide and contribute to other studies about the topic.

6. REFERENCES

Anderson, E. W. y Salisbury, L. C. (2003). The formation of market-level expectations and its covariates. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(1), 115-124. https://doi.org/10.1086/374694

Ardiyanti, H., Sunarwinadi, I. R. y Rusadi, U. (2022). Visualization on Twitter Activism Networks and Opinion Leaders: The Case of# FreeWestPapua. Jurnal The Messenger, 14(1), 36-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.26623/themessenger.v14i1.4049

Berelson, B., Lazarsfeld, P. F. y McPhee, W.N. (1954). Voting: a study of opinion formation in a presidential campaign. University of Chicago PressVoting.

Black, J. S. (1982). Opinion leaders: Is anyone following? Public Opinion Quarterly, 46(2), 169-176. https://doi.org/10.1086/268711

Bone, P. F. (1995). Word-of-mouth effects on short-term and long-term product judgments. Journal of Business Research, 32(3), 213-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(94)00047-I

Bourse, M. y Yücel, H. (2012). İletişim bilimlerinin serüveni. Ayrıntı Yayınları.

Brown, D. y Hayes, N. (2008). Influencer marketing: Who really influences your customers? Elsevier.

Creswell, J. W. y Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W. y Plano Clark, V. L. (2015). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage

DeFleur, M. L. y DeFleur, M. H. (2022). Mass communication theories, explaining origins, processes, and effect. Routledge.

Dubois, E. y Gaffney, D. (2014). The multiple facets of ınfluence. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(10), 1260-1277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214527088

Hansen, A. (2003). İletişim araştırmalarında içerik çözümlemesi. M. S. Çebi (Ed.) In İçerik çözümlemesi (pp. 49-102). Alternatif Yayınları.

Herr, P. M., Kardes, F. R. y Kim, J. (1991). Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information on persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(4), 454-462. https://doi.org/10.1086/208570

Huang, C. C., Lien, L. C., Chen, P. A., Tseng, T. L. y Lin, S. H. (2017). Identification of Opinion Leaders and Followers in Social Media. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Data Science, Technology and Applications (DATA 2017), 180-185.

Jalilvand, M. R., Esfahani, S. S. y Samiei, N. (2011). Electronic word-of-mouth: challenges and opportunities. Procedia Computer Science, 3, 42-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2010.12.008

Katz, E. (1957). The two step flow of communication: an up to date report on an hypothesis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 21(1), 61-78. https://doi.org/10.1086/266687

Katz, E. y Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal ınfluence: the part played by people in the flow of mass communications. The Free Press.

Khan, N. S., Ata, M. y Rajput, Q. (2015). Identification of opinion leaders in social network. In 2015 International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies (ICICT) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

Knoll, J. y Proksch, R. (2017). Why we watch others' responses to online advertising–investigating users' motivations for viewing user-generated content in the context of online advertising. Journal of Marketing Communications, 23(4), 400-412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2015.1051092

Kühn, J. y Riesmeyer, C. (2021). Brand Endorsers with Role Model Function: Social Media Influencers’ Self-Perception and Advertising Literacy. MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis der Medienbildung, 43, 67-96.

Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B. y Gaudet, H. (1960). The people’s choice: how the voter makes up his mind a presidential campaign. Columbia University Press.

Lewis, T. G. (2009). Ciencia de redes: teoría y práctica. John Wiley & Sons.

Li, F. y Du, T. C. (2011). Who is talking? an ontology-based opinion leader identification framework for word-of-mouth marketing in online social blogs. Decision Support Systems, 51(1), 190-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2010.12.007

Lycarião, D. y Santos, M. A. D. (2017). Bridging semantic and social network analyses: the case of the hashtag# precisamosfalarsobreaborto (we need to talk about abortion) on Twitter. Information, Communication & Society, 20(3), 368-385. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1168469

Myers, J. H. y Robertson T. S. (1972). Dimensions of opinion leadership. Journal of Marketing Research, 9, 41-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377200900109

Nisbet, M. C. y Kotcher, J. E. (2009). ¿Un flujo de influencia en dos etapas? Campañas de líderes de opinión sobre el cambio climático. Science Communication, 30(3), 328-354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008328797

Polegato, R. y Wall, M. (1980). Information Seeking by Fashion Opinion Leaders and Followers. Home Economics Research Journal, 8(5), 327-338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X8000800504

Pop, R. A., Săplăcan, Z., Dabija, D. C. y Alt, M. A. (2022). The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(5), 823-843. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1895729

Qiang, X., Huiqi, Z., Ali, F. y Nazir, S. (2021). Criterial Based Opinion Leader’s Selection for Decision-Making Using Ant Colony Optimization. Scientific Programming, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4624334

Ratasuk, A. (2019). Identifying online opinion leaders and their contributions in customer decision-making process: A case of the car industry in Thailand. APHEIT International Journal, 8(1), 37-60.

Rogers, E. M. (1983). Diffusion of innovations. The Free Press.

Saad, S., Salman, A., Abdullah, M. Y. y Lyndon, N. (2018). The Influence of Opinion Leader Amongst Oil Palm Smallholders. Information: International Information Institute, 21(6), 1801-1810.

Schiffman, L. G. y Wisenblit, J. L. (2019). Consumer Behavior. (Twelfth Edition). Pearson Education.

Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L. y Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. ınfluencer endorsements in advertising: the role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 258-281.

Shoham, A. y Ruvio, A. (2008). Opinion leaders and followers: a replication and extension. Psychology & Marketing, 25(3), 280-297. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20209

Summers, J. O. (1970). The identity of women's clothing fashion opinion leaders. Journal of Marketing Research, 7(2), 178-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377000700204

Tokgöz, O. (1977). Siyasal haberleşme ve karar verme. Amme İdaresi Dergisi, 10(4), 85-103.

Tsang, S. J. y Rojas, H. (2020). Opinion leaders, perceived media hostility and political participation. Communication Studies, 71(5), 753-767. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2020.1791203

van Eck, P. S., Jager, W. y Leeflang, P. S. (2011). Opinion leaders' role in innovation diffusion: A simulation study. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28(2), 187-203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2011.00791.x

Weimann, G., Tustin, D. H., Van Vuuren, D. y Joubert, J. P. R. (2007). Looking for opinion leaders: traditional vs. modern measures in traditional societies. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 19(2), 173-190. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edm005

Yıldırım, A. y Şimşek, H. (2016). Sosyal bilimlerde nitel araştırma yöntemleri. Seçkin Yayıncılık.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING, AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors Contributions:

Conceptualization: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Methodology: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Software: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Validation: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Formal Analysis: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Data Curation: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Writing-Original Draft Preparation: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Writing-Review and Editing: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Visualization: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Supervision: Yaşa, Hüseyin. Project Administration: Yaşa, Hüseyin and Birsen, Haluk. All authors have read and approved the final published version of the manuscript: Yaşa, Hüseyin and Birsen, Haluk.

Funding: This research did not receive external funding.

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest between the authors.

AUTHORS:

Hüseyin Yaşa: He completed 2 years of her undergraduate education at Gaziantep University, Faculty of Communication, Department of Journalism, and the last 2 years of her undergraduate education at Akdeniz University, Faculty of Communication, Department of Journalism in Antalya. He completed his master's degree from Antalya, Akdeniz University, Institute of Social Sciences, Department of Journalism in 2017. Currently, he completed her PhD education at Eskişehir, Anadolu University, Institute of Social Sciences, Press and Broadcasting Department and as a YÖK 100/2000 Social Media Studies, TÜBİTAK 2211-A scholar and continues he research as an independent researcher. He academic interests and topics include communication and social media studies, new communication technologies, digital media, new media, journalism, semiotics, hate speech, gender, influencers and opinion leadership.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0589-0842

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=GTt1RDUAAAAJ&hl=tr

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hueseyin-Yasa

Academia.edu: https://anadolu.academia.edu/H%C3%BCseyinYa%C5%9Fa

Publons: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/author/record/ACQ-5460-2022

Haluk Birsen: He completed his master's degree from Eskişehir, Anadolu University, Institute of Social Sciences, Press and Broadcasting in 2000. Currently, professor of the Department of Communication and Press- Broadcasting at the Anadolu University. Her lines of research: data journalism, dijital media, social media, journalism, new media, journalism ethics, internet journalism.

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8760-3792

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=c3xm86kAAAAJ&hl=tr&oi=ao

Academia.edu: https://anadolu.academia.edu/HalukBirsen

Publons: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/author/record/865854